Finding Common Ground (1991-1993)

In late November 1991, after nearly two years of talks about talks, an All-Party Preparatory Meeting agreed on a permanent negotiating forum to be named the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). The CODESA talks that began in December 1991 were a significant milestone. They were, however, beset by multiple breakdowns and deadlocks caused by the violence that engulfed the country, as well as clashes around the nature and outcomes of the constitution-making process. After the Bisho massacre, the talks collapsed. A new way forward had to be forged.

This timeline gives an overview of the story of the first three years of the negotiations process.

Image of the banner outside of CODESA / Preparations for CODESA. Graeme Williams

20 - 21 December 1991

CODESA

“All of us were there to negotiate a future for South Africa. We had to come out with one constitution – not the ANC or the DP or the NP or the traditional leaders’ constitution.”

- Mavivi Myakayaka-Manzini, then member of the ANC Women’s Section and the Constitutional Committee

Nineteen organisations meet at the World Trade Centre under the banner of CODESA - the Convention for a Democratic South Africa. The drab, unimaginative building in Kempton Park is transformed into the first space for democratic discussion in South African history. Here, the transition from apartheid to democracy begins.

Image of the banner outside of CODESA / Preparations for CODESA. Graeme Williams

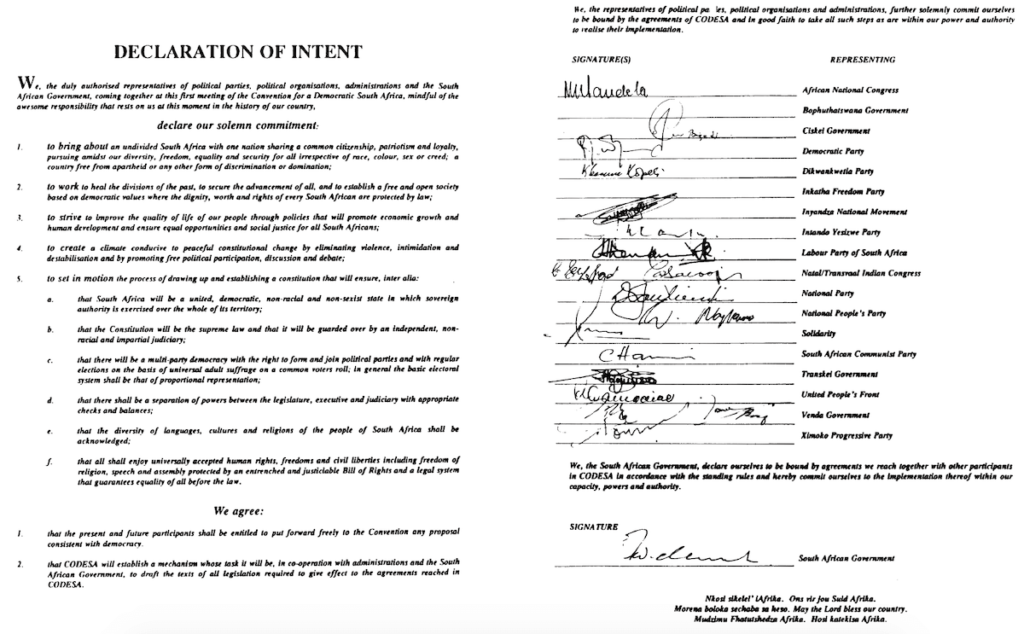

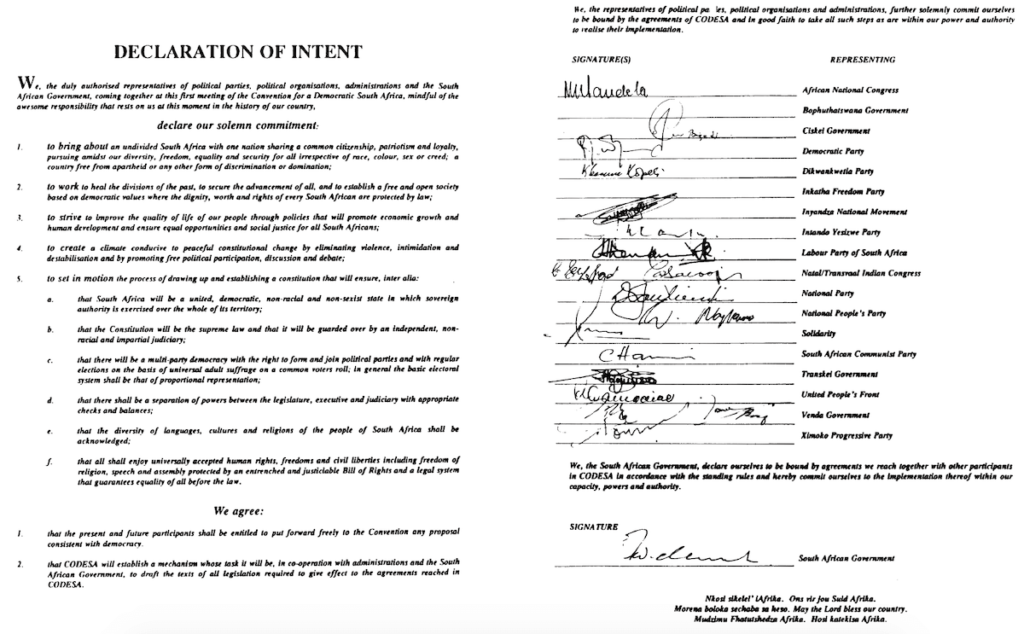

Signed document: Declaration of Intent, 21 December 1991. National Archives and Record Service of South Africa

20-21 December 1991

The Declaration of Intent

The parties sign the Declaration of Intent and pledge themselves to an ‘undivided single South Africa’. The Bophuthatswana government refuses to sign as it objects to the loss of the sovereignty of the homeland. The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) also refuses to sign as the document points away from a federal system of government option which would affect the IFP’s control over its home province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Signed document: Declaration of Intent, 21 December 1991. National Archives and Record Service of South Africa

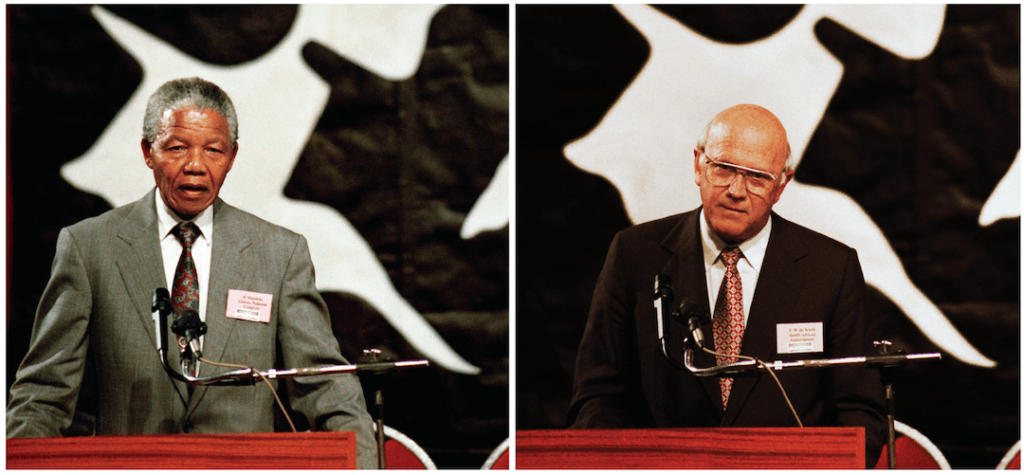

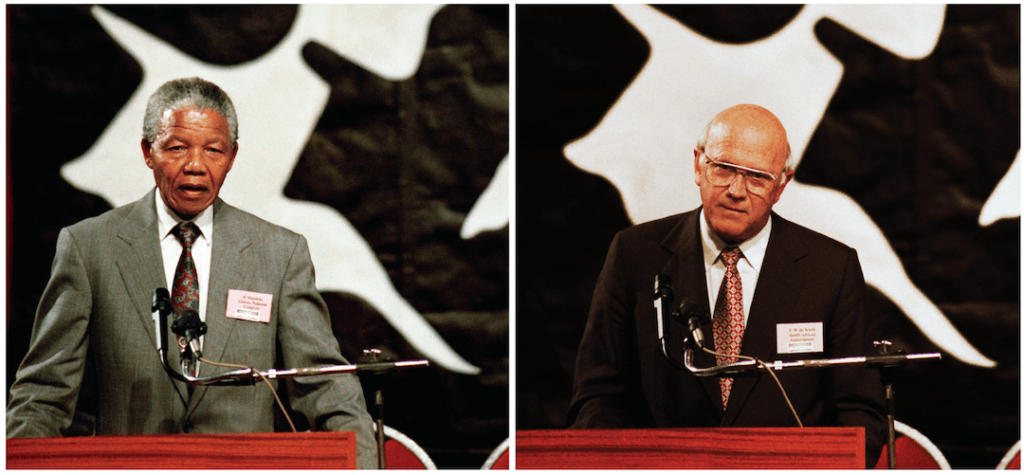

Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk in an angry exchange just before the end of the opening session of CODESA. Graeme Williams

20-21 December 1991

CODESA 1 - A fraught end to the opening sessions

“I am gravely concerned about the behaviour of Mr. de Klerk today. He has launched an attack on the African National Congress, and in doing so he has been less than frank. Even the head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime – as his is – has certain moral standards to uphold. If a man can come to a conference of this nature and play this type of politics, then very few people would like to deal with such a man.”

- Nelson Mandela’s response to de Klerk’s accusations that the MK is responsible for the political violence

Directly after the signing of the Declaration, FW De Klerk makes a hard-hitting speech, saying that the African National Congress (ANC) is “an organisation which remains committed to an armed struggle and cannot be trusted”. When De Klerk is finished, Nelson Mandela lambasts him for violating an undertaking not to discuss the armed struggle at this stage. Pointing his finger at De Klerk, he says with barely controlled anger, “This man is not to be trusted”. CODESA delegates listen to Mandela’s fury, motionless. De Klerk struggles to control his voice as he takes to the podium saying that the disagreement was an example of “how democracy should work”. He makes an impassioned plea for goodwill at CODESA.

Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk in an angry exchange just before the end of the opening session of CODESA. Graeme Williams

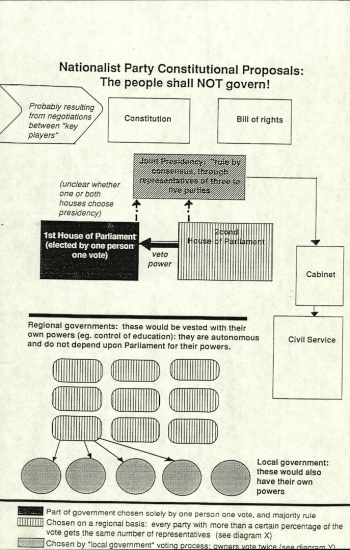

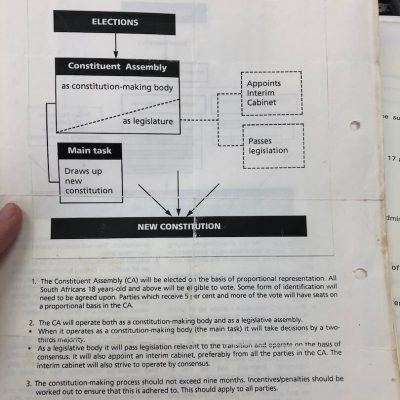

Diagrams from the ANC’s Political Education Discussion Paper of November 1991, showing the differences in the power of the majority in the NP and ANC proposals. The areas shaded in black represent bodies that are elected by one person, one vote. Dotted or striped areas represent bodies that are elected through mechanisms other than the majority vote. Albie Sachs Collection, UWC Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archives

March 1992

A breakdown in the negotiations

In the first months of 1992, political violence was worse than ever. Accusation follows counter-accusation about the causes of the rising death toll. Negotiations have also stalled over a constitutional vision for the country. The NP clings to notions of the protection of minorities and says that an elected majority would “swamp the constitution-making process”. As before, the ANC advocates for a non-racial democracy with an emancipatory Bill of Rights that protects all. Negotiations break down over these issues.

Diagrams from the ANC’s Political Education Discussion Paper of November 1991, showing the differences in the power of the majority in the NP and ANC proposals. The areas shaded in black represent bodies that are elected by one person, one vote. Dotted or striped areas represent bodies that are elected through mechanisms other than the majority vote. Albie Sachs Collection, UWC Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archives

March 1992

Mandela lays out concrete and achievable conditions for the resumption of negotiations. A primary condition is the establishment of an interim government. (This is later transformed into a demand for a Transitional Executive Council (TEC) that will oversee free and fair elections.)

The last whites-only vote in South Africa is the March 1992 referendum. Paul Weinberg

17 March 1992

FW De Klerk comes under attack from conservatives

In the meantime, conservative resistance to negotiations is hardening. De Klerk calls for a referendum amongst white voters to test his mandate for change. Black peopleare insulted by the poll that once again excludes them on racial grounds but Mandela urges his supporters not to disrupt the referendum and even calls on white ANC supporters to vote yes. The NP wins an overwhelming victory in favour of continuing with negotiations. The National Party returns to CODESA with renewed confidence and a misguided belief that they can retain power.

The last whites-only vote in South Africa is the March 1992 referendum. Paul Weinberg

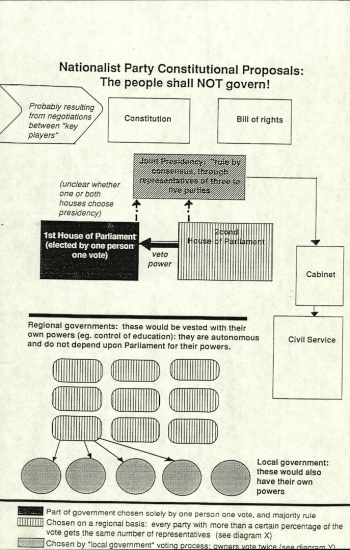

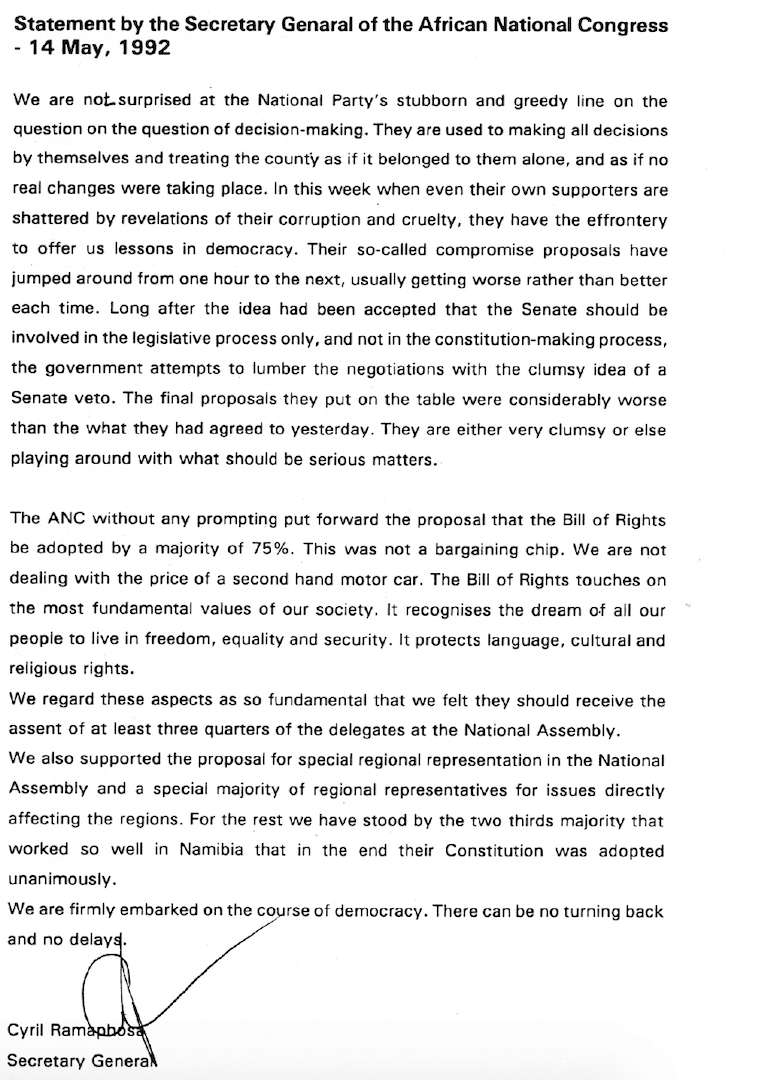

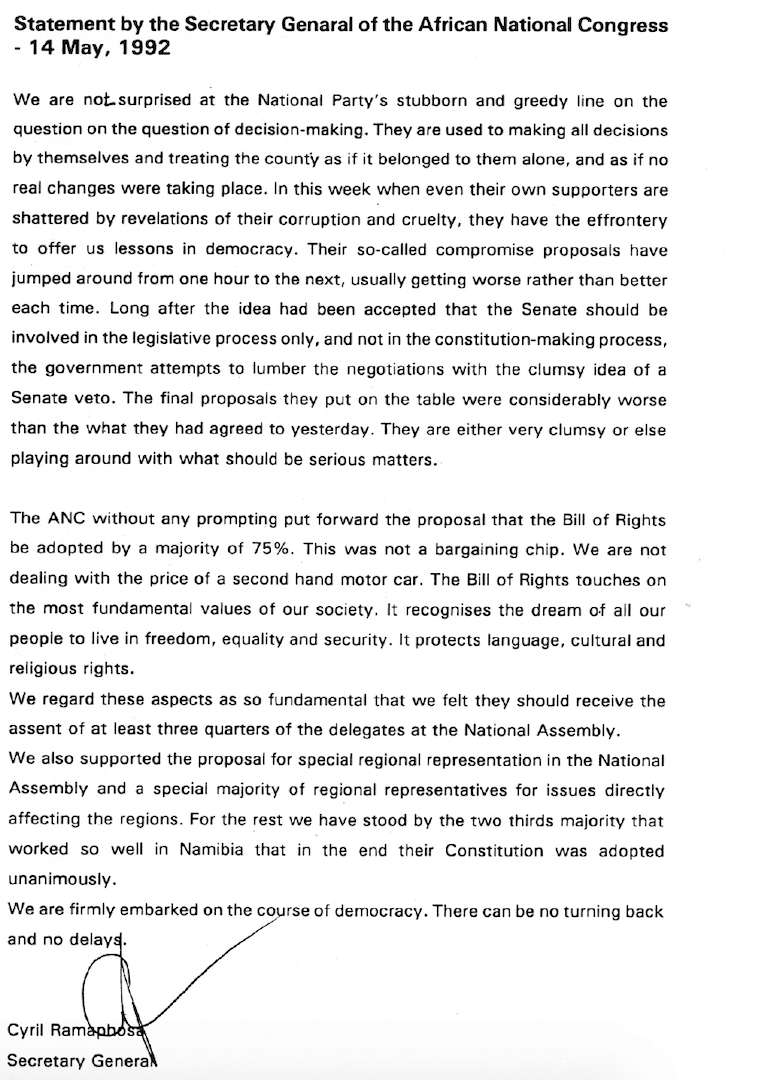

Statement signed by ANC Secretary-General Cyril Ramaphosa at the time of the ANC’s withdrawal from the negotiations, 14 May 1992 UWC / Robben Island Museum / Mayibuye Archives

15-16 May 1992

Deadlock at CODESA II

“I was convinced at the time that the government was not negotiating in good faith and that in actual fact it was attempting to entrench certain unacceptable supposed constitutional principles … So I was happy that we actually had a breakdown … ”

- Brigitte Mabandla, then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

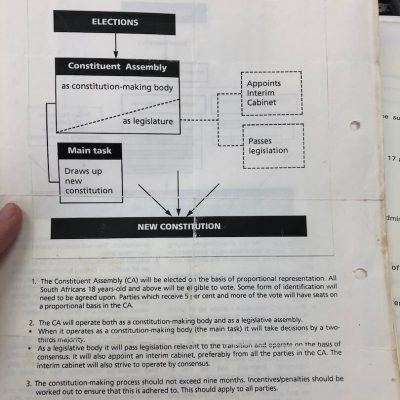

On 15 and 16 May, CODESA II or 2 as it is known, deadlocks over the question of the special majorities required to adopt a final constitution. The government wants important aspects of a new constitution to be settled or subject to change only by a 75% majority before any constitution-making body comes into being. On the other hand, the ANC insists that only a popularly-elected constituent assembly with a relatively free hand to write a new constitution should make that decision.

Statement signed by ANC Secretary-General Cyril Ramaphosa at the time of the ANC’s withdrawal from the negotiations, 14 May 1992 UWC / Robben Island Museum / Mayibuye Archives

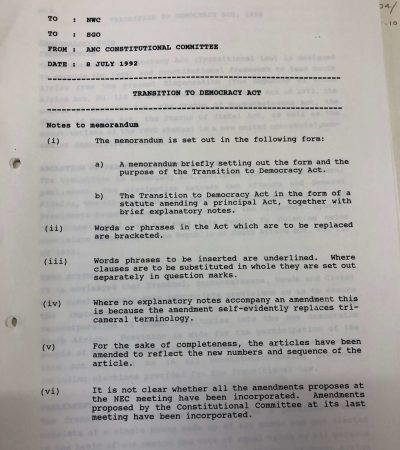

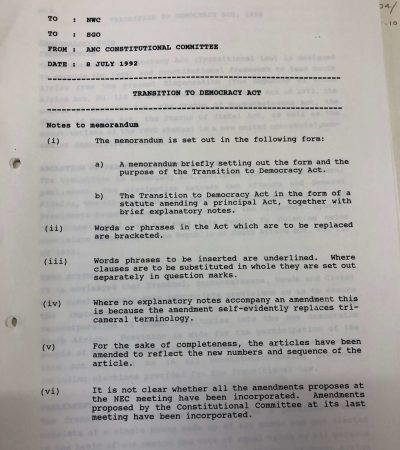

Transition to Democracy Act.Wits Historical Papers

28-31 May 1992

ANC proposes the Transition To Democracy Act

The Act provides constitutional guidelines for the transfer of power to the majority in a democratic society. Ultimately it informs the draft Interim Constitution in 1993.

Transition to Democracy Act.Wits Historical Papers

Comrades protesting in Alexandra. Graeme Williams

June 1992

Rolling mass action

“The breaking off of talks marked an important return for the ANC to the politics of mass mobilisation. It served to remind the illegitimate regime that they were negotiating with a political movement which had the support of the majority of South Africans.”

- Cyril Ramaphosa, then chair of the ANC’s Negotiations Commission, at an ANC press conference

The ANC, in Alliance with the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), decides to demonstrate its power for change through the use of ‘rolling mass action’, in the hope that strikes and street demonstrations would force the NP to agree on an interim government and a non-racial democracy. The alliance also demands that De Klerk puts an end to the crippling violence in the country.

Comrades protesting in Alexandra. Graeme Williams

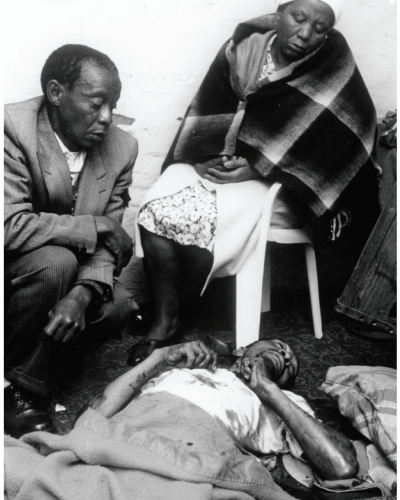

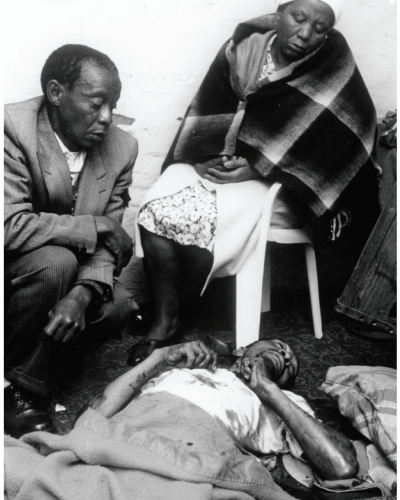

Relatives with an injured victim of the massacre. Avusa

17 June 1992

The final straw

“I am convinced that we are not dealing with human beings but animals. We will not forget what the NP and IFP have done to our people."

-Nelson Mandela speaking at Boipatong after the massacre

Ongoing political violence between the ANC and IFP reaches its climax with the Boipatong Massacre. IFP hostel dwellers attack residents of the township in their homes in the middle of the night. Forty-nine people are killed and many more are injured. Others die in the coming days.

Relatives with an injured victim of the massacre. Avusa

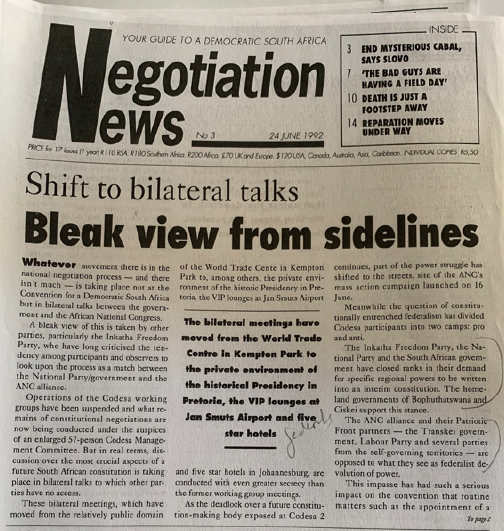

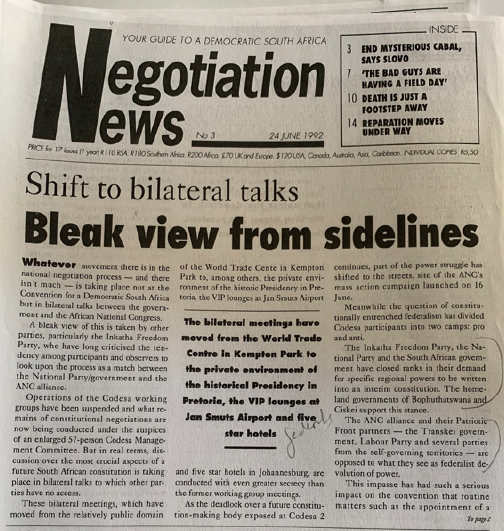

“Negotiation News 24 June 1992.” UWC / Robben Island Museum / Mayibuye Archives

23 June 1992

Negotiations break down

“One of the saddest developments in the transformation of the country and the most blatant example of the NP’s dual strategy of prolonging negotiations indefinitely while conducting a reign of terror against black communities.”

-Cyril Ramaphosa, then chair of the ANC’s Negotiations Commission

Relations between the apartheid government and the ANC reaches an all-time low. The ANC accuses the NP of having a hand in the Boipatong Massacre, suspends talks and issues a set of demands. The Boipatong Massacre proves to be a turning point in South Africa’s history – just as the Sharpeville Massacre had been 32 years earlier. It changes De Klerk’s status forever, and Mandela takes on the mantle of leadership of the country. The NP becomes a pariah in the townships.

“Negotiation News 24 June 1992.” UWC / Robben Island Museum / Mayibuye Archives

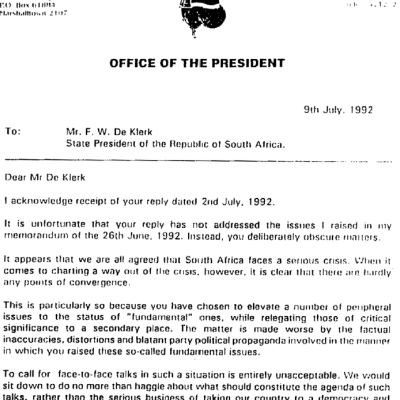

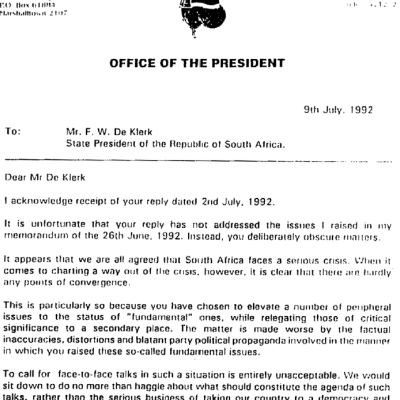

Correspondence highlighting the tension between Mandela and De Klerk after Boipatong. University of Fort Hare / ANC Archive

26 June 1992

Mandela sends an angry letter to De Klerk

Mandela demands that the government address the issue of police involvement in violent massacres and that it accepts the inevitable fact of majority rule.

Correspondence highlighting the tension between Mandela and De Klerk after Boipatong. University of Fort Hare / ANC Archive

2 July 1992

De Klerk responds to Mandela’s letter

De Klerk responds. He denies involvement in the violence but takes steps to control it. He refuses to commit to majority rule. In the same breath, he refers to the issue of the future of hostels to the Goldstone Commission, he issues a proclamation banning dangerous weapons and agrees to the international monitoring of violence.

Placard accusing FW de Klerk of being a murderer during the Defend Democracy campaign in Cape Town. Benny Gool / Oryx Archives

2 August 1992

United Nations (UN) Secretary-General, Cyrus Vance, heads for South Africa

After holding a special session about violence in South Africa, the UN Security Council adopts special resolution 765 calling for a representative of the Secretary-General, Cyrus Vance, to visit SA. In August 1992, the UN Monitoring Committee under the leadership of Vance, arrives in the country. Vance discusses the release of political prisoners as well as the abandonment of the armed struggle with Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pik Botha.

Placard accusing FW de Klerk of being a murderer during the Defend Democracy campaign in Cape Town. Benny Gool / Oryx Archives

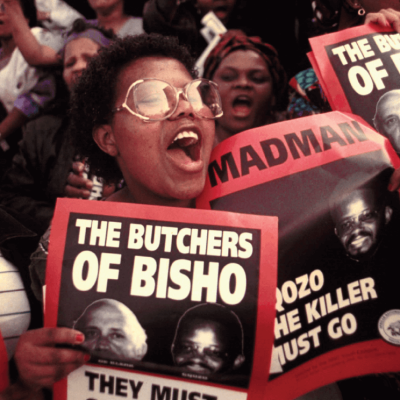

Cartoon depicting the “channel” September 1992. Zapiro 1992

31 August-2 September 1992

A new channel of communication

“For a period … we had practically no progress except for the telephone calls between Cyril and myself just to keep the line going.”

-Roelf Meyer, then chief negotiator for the National Party <

“We knew that it was only through some understanding between us that we could make a real attempt to resolve the problems between the ANC and the government.”

-Cyril Ramaphosa, then chair of the ANC’s Negotiations Commission

The ANC appoints its chair of the Negotiations Commission, Cyril Ramaphosa, to keep communication with the government open through a channel with the NP’s representative, Roelf Meyer.

Cartoon depicting the “channel” September 1992. Zapiro 1992

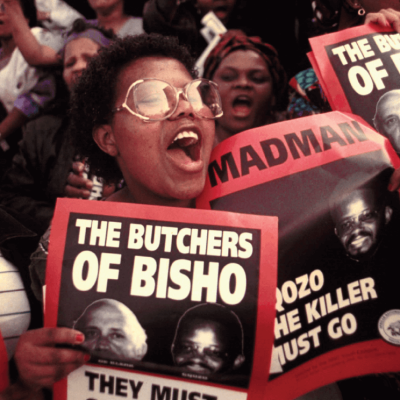

Protesters flee after police open fire during the ANC march on Bisho in the Eastern Cape, 18 September 1992. Greg Marinovich / Africa Media Online

7 September 1992

Bloodshed in Bisho

“Just as we arrived at the razor wire, the shooting began. Then we heard explosions. We all dropped to the ground. Then there was a short pause before a second volley of fire started. Several people in my immediate vicinity were shot. The shooting continued for a minute or two. When the shooting ended, many people were dead and many more were injured. We were shocked and outraged. There had been no provocation by the marchers, who were all unarmed and controlled by marshals.”

-Cyril Ramaphosa, then chair of the ANC’s Negotiations Commission, in a press interview after the massacre

The ANC arranged a march on Bisho, the capital of the ‘independent’ Ciskei homeland as part of its continued rolling mass action campaign. Eighty thousand people participate in a protest to oust the Ciskei’s unpopular military leader, Brigadier Oupa Gqozo, hated by many as a despot. As marchers approach the Bisho stadium, Ciskeian soldiers open fire killing 29 people and injuring hundreds. The media accuses ANC leaders of ‘recklessness’ in leading the march while also recognising that it was the government’s ‘surrogates’ who were responsible for the deaths of so many people.

Protesters flee after police open fire during the ANC march on Bisho in the Eastern Cape, 18 September 1992. Greg Marinovich / Africa Media Online

26 September 1992

Let us start again

While Boipatong caused the negotiations to be broken off, the bloodshed at Bisho leads both sides to seek solutions. A week after the massacre, Mandela compresses the ANC’s 14 preconditions for resuming talks to three. They are the release of 200 disputed political prisoners, the ban on cultural weapons, and the fencing off of 18 migrant workers’ hostels in the Witwatersrand area. There is much to-ing and fro-ing between the government and the ANC before De Klerk announces that the government would accept the ANC’s demands. This is considered a turning point moment in the negotiations.

A protest against those believed to be responsible for the Bisho Massacre. Adil Bradlow

26 September 1992

A milestone pact

Mandela and De Klerk seal their commitment to negotiations by signing the Record of Understanding, which resolves the central drama of the constitution-making process and leads to the resumption of negotiations. Significantly, the NP abandons its demand for ‘entrenchment of power sharing as a constitutional principle’ and its insistence on group rights.

A protest against those believed to be responsible for the Bisho Massacre. Adil Bradlow

Mayibuye Magazine March 1992 “Phase II Sovereign Structures”. South African History Archives

September 1992

Give and take: The Sunset Clause

Joe Slovo introduces the notion of a ‘Sunset Clause’, which allows for power sharing in a Government of National Unity for five years after a democratic election. The white civil service will remain in place.

Mayibuye Magazine March 1992 “Phase II Sovereign Structures”. South African History Archives

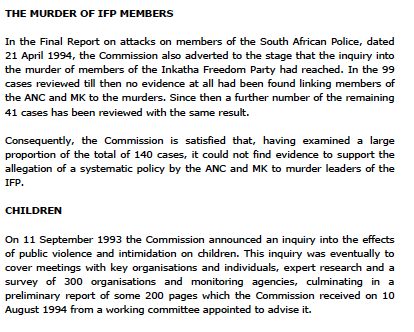

Goldstone Commission Final Report. Hurisa

1 October 1992 - 20 September 1993

FW De Klerk appoints Judge Richard Goldstone to investigate violence

The Goldstone Commission confirms evidence of third force activities. It finds that senior police officers are sponsoring violence and death squads in an effort to try to destabilise South Africa, make elections impossible, and stop the nation’s transition to democracy.

“[There exists] a horrible network of criminal activity among senior South African police force officers who helped to sponsor violence.”

-Justice Richard Goldstone in his report to De Klerk

Goldstone Commission Final Report. Hurisa

This photograph of Bophuthatswana President, Lucas Mangope, CP leader, Ferdi Hartzenberg, IFP leader, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, and Bophuthatswana delegate, Rowan Cronjé, was taken when the homeland governments and right-wing Afrikaner parties formed COSAG. These strange bedfellows were united in their determination to ‘draw a line against the manipulation of the talks’ by the ANC and the government. Avusa

6 October 1992

Concerned South Africans Group (COSAG) is formed

The IFP, Conservative Party (CP) and some homeland governments form an opposition group saying that the ANC and NP have too much power between them. They threaten civil war unless their demands for federalism are met.

This photograph of Bophuthatswana President, Lucas Mangope, CP leader, Ferdi Hartzenberg, IFP leader, Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, and Bophuthatswana delegate, Rowan Cronjé, was taken when the homeland governments and right-wing Afrikaner parties formed COSAG. These strange bedfellows were united in their determination to ‘draw a line against the manipulation of the talks’ by the ANC and the government. Avusa

November 1992

The Further Indemnity Act

This Act allows for the release of all political prisoners who had been convicted as criminals under apartheid. Between late 1992 and 2 February 1993 1 477 prisoners are released.

5 December 1992 - 4 February 1993

Bonding at the ‘bosberade’ (meetings)

The ANC and NP hold a series of meetings in secluded, relaxed settings called ‘bosberade’. They discuss matters of security, violence, the elections, the homelands and planning for a multi-party conference. The purpose of these meetings is to plan the resumption of multilateral negotiations.