Part 1 - The pre-colonial and Union period

Nokuthela Mdima Dube. Date unknown.Cherif Keita

Early women pioneers

Many early women pioneers broke free of the stereotypical roles imposed on them, forged new identities against the odds and led important struggles against oppression. Their names and stories seldom appear in historical records. To name but a few: Krotoa, later named Eva, was an interpreter of Dutch and Portuguese and became a key participant in the trade industry and a negotiator during the frontier wars. Emma Sandile, also known as Princess Emma, was taken away from her family to be educated as a Victorian woman and became a landowner, the first known black woman to hold a land title in South Africa. Nokuthela Mdima Dube was one of the first black women to qualify as a teacher specialising in Music and Home Economics. She became a key activist and with her husband built the Ohlange Institute in Inanda which established the newspaper Ilanga Lase Natal. She co-authored Amagama Abantu (A Zulu Song Book).

Nokuthela Mdima Dube. Date unknown.Cherif Keita

Charlotte Makgoma Manye on the cover of a postcard created in about 1890. Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries

1891

Charlotte Maxeke - The first black woman graduate

Charlotte Makgoma Manye (later Maxeke), known affectionately as the mother of black freedom, first entered the public stage when she joined the African Native Choir for a tour to England and North America in 1896. Whilst she was in London, she attended suffragette meetings and heard women like Emmeline Pankhurst speak about the women’s franchise. She was offered a scholarship to study at Wilberforce University in Ohio and studied under the prominent pan-Africanist scholar, WEB Du Bois.

She became the first black South African woman to earn a university degree and assisted many others to study in the USA. On her return to South Africa, she took her first active steps in organised politics when she attended the annual meeting of the SA Native Convention (SANC) or Ingqungqutela in Queenstown. Because women were not invited to become members of the organisation, she was forced to wait outside, causing a great stir.

Charlotte attended the inaugural conference of the South African Native National Conference (SANNC) in 1912. She went on to break many of the stereotypical roles assigned to women at that time and chipped away at the edifice of authoritarianism that was imposed on women. She also spoke to men as well as women about what she was expecting from them:

“We want men to protect the women of their nation, not men who hurt and endanger women when they become aware of their rights.”

-Charlotte Maxeke, in a speech in 1922

"I regard Mrs Maxeke as a pioneer in one of the greatest of human causes, working in extraordinarily difficult circumstances to lead a people, in the face of prejudice, not only against her race but against her sex. I think that what Mrs Maxeke has accomplished should encourage all men, especially those of African descent."

-WEB Du Bois, leading pan-Africanist activist-intellectual praising his former student in a preface of the 1930 book written about her

Charlotte Makgoma Manye on the cover of a postcard created in about 1890. Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries

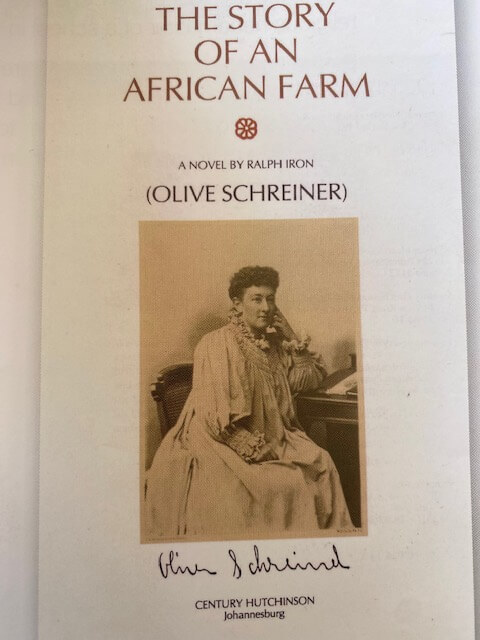

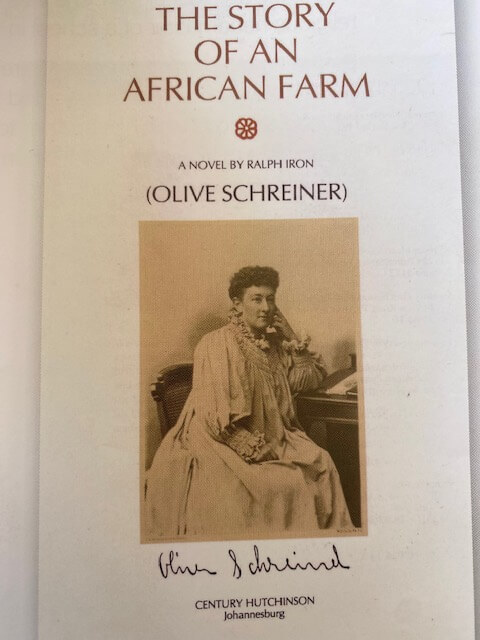

Schreiner only admitted to being the author of this book seven years after it was published.

1905

Olive Schreiner - Author and activist

Olive Schreiner, daughter of a missionary, wrote her book, Story of an African Farm, at the age of 21 under the pseudonym Ralph Iron. It explores the injustice of racism and the oppression of women and it became a sensation in England. When she went back there, she became heavily involved with women suffragettes fighting for votes for women, and in particular got close to Sylvia Pankhurst, a socialist feminist. Schreiner’s book, Women and Labour, showing the connection between women’s struggles and workers’ struggles, became one of the bibles of the women’s movement. On her return to South Africa, she was at first dazzled by Cecil John Rhodes, but after the invasion of what became Rhodesia, she wrote the first great denunciation of Rhodes. When the Union of South Africa was created in 1910, she predicted that it would fail because it did not include the native races. Today, Schreiner is remembered as a foremost South African writer, feminist and social theorist.

“It is delightful to be a woman, but every man thanks the Lord devoutly that he isn’t one.”

-Olive Schreiner in The Story of an African Farm

Schreiner only admitted to being the author of this book seven years after it was published.

An early photograph of Hellen ‘Nellie’ James and her husband, Abdullah Abdurahman, possibly taken on their wedding day, c.1894. Unknown

1900's

Petitioning against passes

From the early 1900s, the colonial governments required every African male person over 16 to carry a service book listing their employer and place of residence. The Orange Free State was the first territory in South Africa to implement the pass laws for women. In 1905, the Orange River Colony Vigilance Association sent petitions and delegations to every level of authority calling for a repeal of women's pass laws. For a decade, these vigilance associations along with the African Political Organisation (APO) in Cape Town, appealed for the repeal of women’s passes. They were supported by the APO Women’s Guild which was formed under the leadership of Scottish-born Mrs Hellen (‘Nellie’) Abdurahman (née James).

“The Guild’s aim is promoting unity among the Coloured women of British South Africa, and to aid and assist towards the uplifting of the race ... to obtain better and higher education for children, and … to assist and encourage as far as possible the work carried on by the men members of the APO.”

-Extract from a 1910 APO report

An early photograph of Hellen ‘Nellie’ James and her husband, Abdullah Abdurahman, possibly taken on their wedding day, c.1894. Unknown

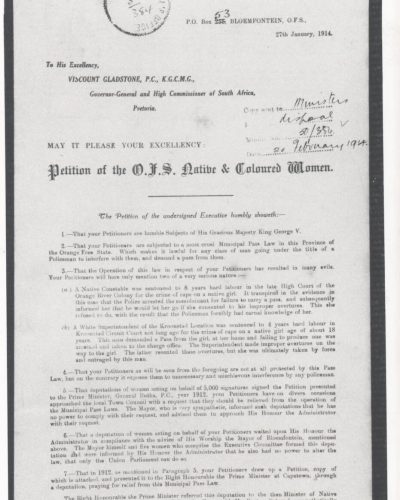

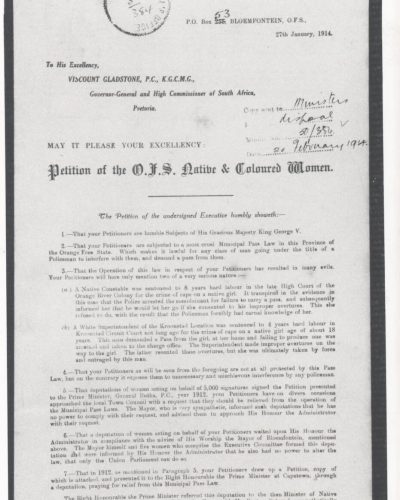

A copy of the Native and Coloured Women’s Association 1914 petition. National Archives and Record Services South Africa

1910

Union and resistance

After the Act of Union in 1910, it became clear that only an act of parliament could change the pass laws. In 1912, the Native and Coloured Women’s Association (NCWA) was formed under the leadership of Catharina Symmons and Katie Louw. They openly defied the law, marching on the local administration offices, delivering petitions and dumping passes. Participants faced arrest. The NCWA also protested against sexual harassment carried out by police officials who were enforcing pass law regulations.

"A white Superintendent of the location demanded a pass from the girl at her home and failing to produce one was arrested and taken to the charge office. The Superintendent made improper overtures on the way to the girl. The latter resented these overtures, but she was ultimately taken by force and outraged by this man."

-The 1914 petition

A copy of the Native and Coloured Women’s Association 1914 petition. National Archives and Record Services South Africa

Rev Walter Rubusana, date unknown. Unknown

1912

Women’s anti-pass delegations

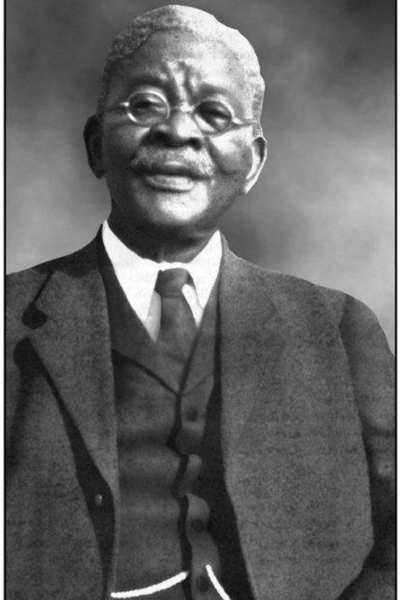

African National Congress (ANC) in 1923, passed a resolution against passes for women, they did not willingly take up the issue. Instead, women took up the cause on their own behalf. In 1912, they petitioned the various provincial governments of the Cape and the Free State to repeal existing laws. On their own initiative, they met with the supposedly liberal Henry Burton, Minister of Finance of the Union, to present a 5 000 signature petition against passes. Their arguments referenced equality and demanded an end to sexual abuse by police. Mpilo Walter Benson Rubusana accompanied the women's deputation to present the petition to the Minister. He is one of many men that would support women’s struggles.

Rev Walter Rubusana, date unknown. Unknown

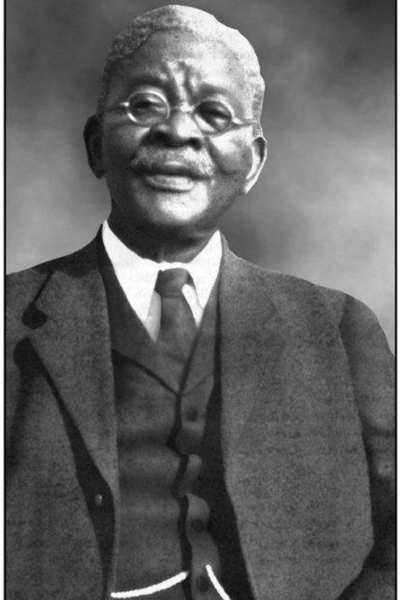

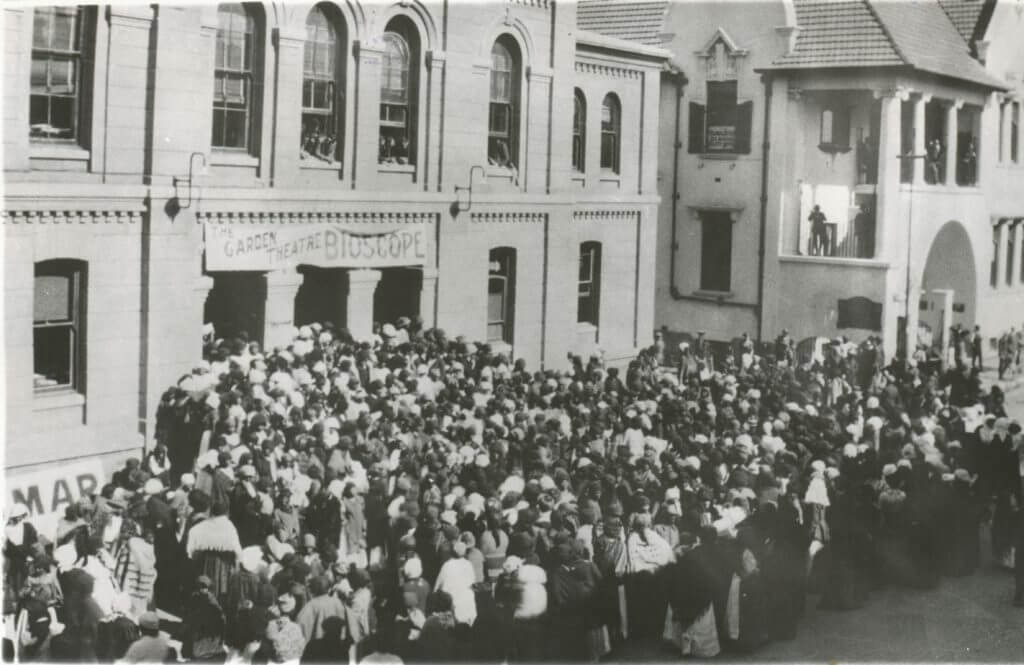

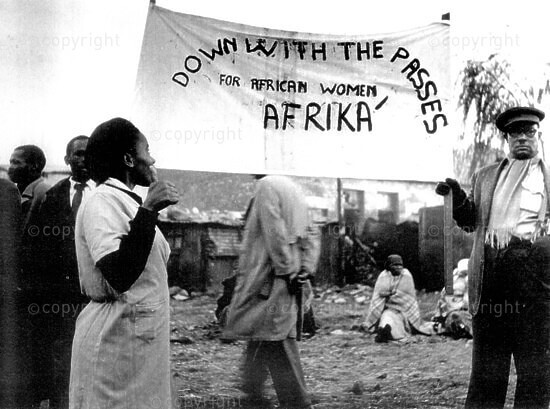

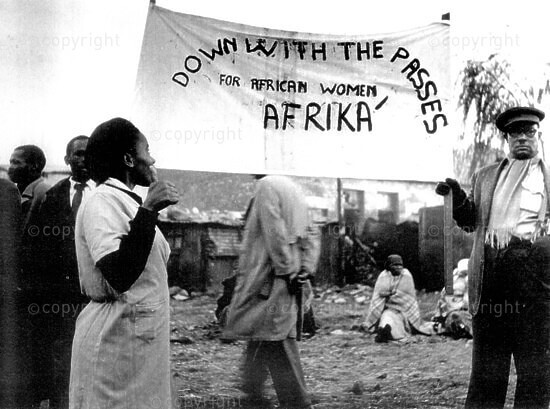

Black and coloured women protesting against pass laws in Bloemfontein, Orange Free State in 1913. National Museum

1913

Anti-Pass protests in Bloemfontein

The women’s appeals to the authorities fell on deaf ears. Indeed, the women of Bloemfontein found themselves targeted for police action to a much greater extent. In May 1913, women launched a passive resistance campaign in the Waaihoek location in Bloemfontein. Women refused to carry the residential permits imposed by the local authorities as these tightly restricted the everyday lives of women. By June, the resistance had escalated into a full-out clash between women and the police. Two hundred angry women demonstrators, carrying sticks, led by Charlotte Makgoma Manye (later Maxeke), marched into town to see the mayor. When he was eventually cornered, he claimed that his hands were tied. The women promptly tore up their passes and generally provoked the authorities into arresting them. They shouted at the police, “We have done with pleading, we now demand!” Eighty women were arrested.

The writer, Sol Plaatje wrote about the strength and courage of these women when he visited them in the Kroonstad Prison:

“They don't care even if they die in jail. They swear they will cure that madness; they will stop their protest only when the law prevents policemen from stopping and demanding passes from other men's wives.”

-Extract from the newspaper, Tsala ea Batho

Black and coloured women protesting against pass laws in Bloemfontein, Orange Free State in 1913. National Museum

Women outside Central jail in prayer with Alan Paton in remembrance of Valliamma R Munuswami Mudaliar, date unknown. Unknown

1913

ransvaal women satyagrahis march

The main mobilisation by Mahatma Gandhi of Indian women in South Africa was over the refusal of the courts to acknowledge Muslim and Hindu marriages as legal marriages, because they were potentially polygamous. Wives were referred to as concubines and their children as illegitimate. As part of the broader passive resistance campaign against unjust laws led by Gandhi, Transvaal women Satyagrahis became actively involved in resistance in 1913. Scores of brave women crossed the Natal-Transvaal border on foot and were arrested and sent to prison in Pietermaritzburg. Many were the wives of men who had been imprisoned during the Satyagraha Campaign and had had to carry the burden of providing for their families while their husbands were detained.

Gandhi saw these women as an important inspiration and said that they were like ‘a lighted match to dry fuel’. Some of the women participating in the march were Mrs Veerammal Naidoo, Mrs N. Pillay, Mrs K Murugasa Pillay, Mrs A Perumal Naidoo, Mrs PK Naidoo, Mrs K. Chinnaswami Pillay, Mrs NS Pillay, Mrs RA Mudalingum, Mrs Bhavani Dayal, Miss Minachi Pillay, Miss Baikum Murugasa Pillay and sixteen year old Valliamma Munusamy Moodaliar. Conditions inside the jail were appalling. Valliamma R Munuswami Mudaliar later died from a fever contracted in prison.

“Armed only with the patriotism of faith, the sacrifices of our mothers and daughters [finding themselves in jail] were particularly severe.”

-Mahatma Gandhi

Women outside Central jail in prayer with Alan Paton in remembrance of Valliamma R Munuswami Mudaliar, date unknown. Unknown

Part 2. The Interwar Years - 1918 - 1945

Charlotte Maxeke. Historical Papers AB Xuma Collection

1918

Charlotte Maxeke and the Bantu Women’s League

By 1918, women's protests against the pass laws had spread throughout the country. A group of women, led by Charlotte Maxeke, established the Bantu Women’s League (BWL) in response to the threat of the Orange Free State government to reintroduce passes for black women. The BWL’s work included representations to the authorities through delegations, meeting with the prime minister and other officials, and through appearing before commissions of inquiry. For example, Maxeke gave evidence before the Moffat Commission on the indignities women suffered from carrying the night passes. As a result of these efforts, pass law enforcement for women in the Free State was relaxed followed by the eventual exclusion of women from pass laws on a national basis in 1923.

“This work is not for yourselves - kill the spirit of ‘self’ and do not live above your people, but live with them. If you can rise, bring someone with you. Do away with that fearful animal of jealousy - kill the spirit, and love one another as brothers and sisters.”

-Charlotte Maxeke, at the second conference of the National Council of African women, 1930

Charlotte Maxeke. Historical Papers AB Xuma Collection

Mary Fitzgerald’s election poster for the Johannesburg Municipal Election. Wikipedia

1911

‘Pickhandle Mary Fitzgerald’

Mary Fitzgerald was an Irish-born South African political activist, remembered as the first female trade unionist in the country. In 1911, during Johannesburg’s first major strike by white tram workers, Fitzgerald spoke at a protest meeting while holding a pickhandle that had been dropped by mounted police to break up the strike. The pickhandle became her trademark, earning her the nickname of ‘Pickhandle Mary’. Fitzgerald went on to lead a group of women to sit on the tracks and they were successful in keeping trams from leaving the station. She was involved in many other strikes in Johannesburg leading her ‘pickhandle brigade’ to break up anti-union meetings. She was influential in a miners’ strike during the miners’ strikes of 1913 and 1914, and during the tumultuous 1922 strike. She also travelled to England to speak at huge labour rallies.

In the first elections for the Johannesburg municipality in 1915, Mary was elected to the city council and served until 1921. She was the first woman to hold public office in the city. She was a role model for other women to become public figures and also set the tone for women’s trade union activism in the years that would follow.

Mary Fitzgerald’s election poster for the Johannesburg Municipal Election. Wikipedia

Members of the Communist Party of South Africa. Ray Alexander can be seen in the centre surrounded by women activists. Date unknown. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

1920's

The rise of women in trade unions

In the aftermath of the First World War, thousands of women – both African and Afrikaner – were pushed off the land and forced to take up work in the city. Here they faced poor and exploitative working conditions. This era saw a burgeoning of activity in factories across the country. Women joined unions and fought for issues specifically affecting women - such as sexual abuse, low wages and unfair labour demands - to become part of the trade union programmes. A striking feature of the union movement was that women were mobilised along gender and class lines rather than that of race. Unions gave women a new public platform that obliged men to start treating them as equals - although this often involved resisting the conventional roles imposed by their fellow male unionists. Women also had to fight for their rights to participate in any form of organisation outside of the home. Although women became more active in the union movement, they were still largely absent from the leadership. Exceptions to this were Johanna Cornelius, Emma Mashinini, Lydia Kompe, Maggie Magubane and Ray Alexander Simons.

“They [male organisers] expected me to do things … I got used to resisting, saying, 'I am not here to become a tea girl.’ .... My husband also didn't take anything in the union into account … He expects me to be at home between 5.30 and 6.00 pm. After I became a shop steward, I had many meetings. That made him very unhappy and it made our life very miserable. He couldn't see why I was involved in this … He was scared that I’d land in jail … I think it's time for women to come together and see this thing as a major problem for us. Eventually we must achieve the same rights.”

-Lydia Kompe, Transport and General Workers Union

“... with discussion around democracy and equality within the unions, and the increasing involvement of women … we hope to start changing attitudes.”

-Maggie Magubane, General Secretary of the Sweet Food and Allied Workers Union

Members of the Communist Party of South Africa. Ray Alexander can be seen in the centre surrounded by women activists. Date unknown. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

Front page of Black Administration Act No 38 of 1927. South African Government

1927

Black Administration Act 38 of 1927

This act declared that the Governor-General was the Supreme Chief of all natives. In providing for the control of all African people, it established a separate and inferior system of justice for Africans. So-called Native Law was interpreted by white Native Commissioners in a way that formalised patriarchy and subjected women to the control of their fathers and husbands. Women were barred from inheriting estates regardless of their marital relationship or familial ties to the deceased. Instead, the nearest living male relative inherited all the relevant property. Furthermore, African black women were now regarded as minors, irrespective of their age or marital status. As a result, black women had no legal parental rights concerning their children.

Front page of Black Administration Act No 38 of 1927. South African Government

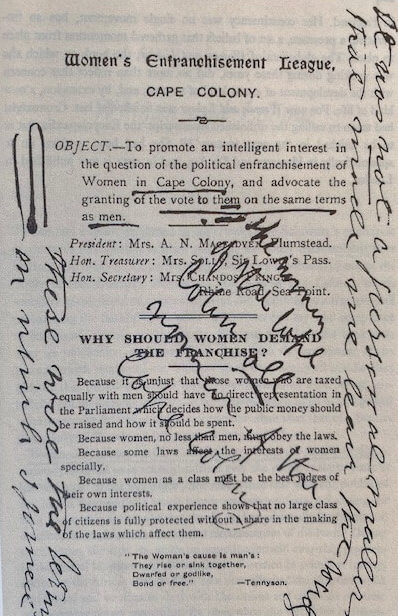

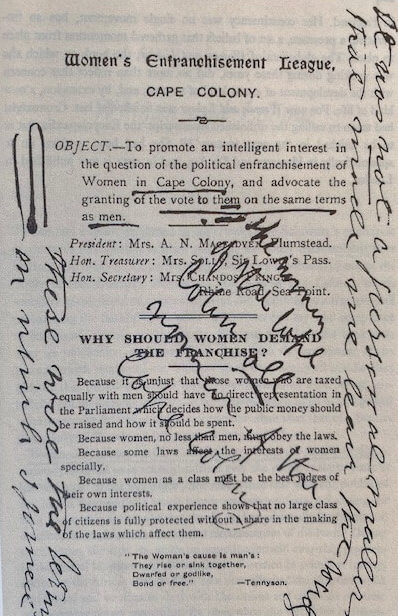

Schreiner angrily scribbled “all women of the Cape colony” on this league pamphlet, 1980. First and Scott

1930

White women fight for the vote

Women's suffrage was a persistent issue in white politics between 1892, when a motion calling for a qualified franchise for women was defeated in the Cape House of Assembly, and 1930, the year when Parliament enfranchised all white women over the age of 18. The 4 000 or so members of the national women's suffrage movement - who proclaimed that they would now take their rightful place as equals with men in political life - had failed to forge any sense of sisterhood or commonality. Their movement epitomised white women’s preparedness to fight for the vote for a mere quarter of the women in the country rather than for general suffrage for all women. Indeed, Olive Schreiner, who was once the vice-president of the Cape Women’s Enfranchisement League, resigned in 1914 in protest against white women’s endorsement of a racial basis to the franchise campaign. In the end, the white women’s vote had less to do with the efforts of the suffragette movement than with Herzog’s desire to slash the proportion of black voters in relation to white voters in the Cape Colony. In effect the weight of the black vote decreased from 3.1% to 1.4%.

“Compared to the suffrage campaign being waged by Emily Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union in England, the SA campaign was a timid and decorous affair.”

-Cheryl Walker, author and gender activist

Schreiner angrily scribbled “all women of the Cape colony” on this league pamphlet, 1980. First and Scott

Charlotte Maxeke, date unknown. Unknown

1930's

A National Council for African Women (NCAW)

This organisation was formed at the All-African Convention to broaden and deepen black women’s political voice. Charlotte Maxeke was elected as president. After Maxeke’s death in 1939, teacher and social worker, Minah Soga, was appointed president. Unlike the ANC, the NCAW created women’s self-help and social activist organisations across the country as a form of political mobilisation.

“Do not live above your people, but live with them. If you can, bring someone with you. Do away with that fearful animal jealousy − kill that spirit [of self] and love one another as brothers and sisters. The animal that will tear us to pieces is tribalism. I saw the shadow of it and it should cease to be. Stand by your motto – the golden rule.”

-Charlotte Maxeke’s Presidential address at the NCAW conference, 1938

Charlotte Maxeke, date unknown. Unknown

1932

Amadodakazi – Baradi Ba Africa / Daughters of Africa (DOA)

Cecilia Lillian Tshabalala, the leader of the DOA, explained that this federal union of women’s organisations was formed with three principal goals: "To promote sisterhood, to develop a community of mutual service, and to better society.” By the early 1940s, DOA branches were formed across the then provinces of Natal and the Transvaal. They were a small but influential forum for women’s engagement in nationalist public culture working alongside all-female social welfare organisations such as the NCAW and the Zenzele Clubs. The DOA played a key role in civic struggles such as the Alexandra Bus Boycotts of 1943 for example. Members included prominent women activists such as Nokutela Dube, Joyce Mpama, Bertha Mkize, Madie Beatrice Hall Xuma and Nokukhanya Bhengu.

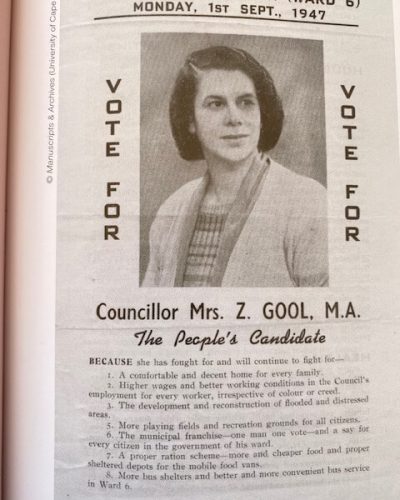

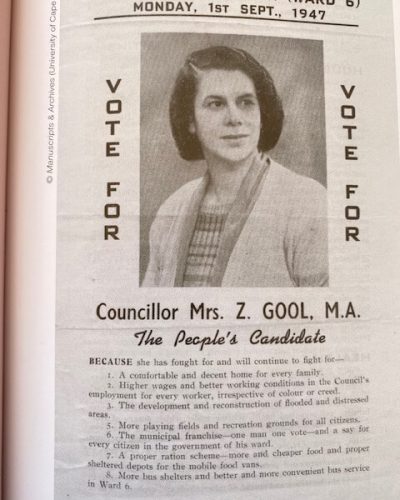

Gool’s poster for election as ward council. Manuscripts and Archives, University of Cape Town

1938

Cissie Gool and the National Liberation League (NLL)

Gool was one of South Africa’s greatest political leaders. Born in Cape Town in 1897 to a well-known political family, Gool was determined and independent from a young age. She became the first black woman to receive a degree from the University of Cape Town. Instead of becoming a psychologist, however, she formed the National Liberation League of South Africa (NLL) and committed to end racial inequality. In 1938, she organised a march against the Cape Government to protest against plans to introduce separate areas for white and black people to live in. Gool captivated the crowds with her passionate oratory and her singing in an electrifying soprano.

Whilst president of the NLL, Gool stood for elections to become the Municipal Councillor for District Six. She won and remained Councillor of the area for 13 years. She became known as the ‘Jewel of District Six’ for the significant impact she made on people’s day-to-day lives. She resigned from the Council in protest against the apartheid government’s introduction of the Group Areas Act in 1950. Thereafter, Gool was accused of being a communist, and was banned from all political activity. Gool found other avenues to continue the fight. She studied law and became the first black women advocate at the Cape Town bar.

Gool’s poster for election as ward council. Manuscripts and Archives, University of Cape Town

Madie Hall Xuma,1952. Jurgen Schadeberg / Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

1943-1948

The ANC Women’s League (ANCWL)

In 1941, a resolution was passed to revive the women's section of ANC. Two years later, women were given access to formal ANC membership and shortly thereafter, the ANC Women’s League was launched – although the launch date is recorded as 1948 in the ANC archives. Madie Hall Xuma was its first president, followed by Ida Mtwana. The ANCWL was prominent in the 1952 Defiance Campaign and active in fighting against passes, Bantu Education and other social issues. Women’s activism impacted on the male dominated ANC leadership culture. In 1956, Lilian Ngoyi, then Women’s League president, was elected to the ANC National Executive Committee.

Madie Hall Xuma,1952. Jurgen Schadeberg / Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

A Passive Resistance Campaign meeting at Durban's Red Square. UWC-Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archives

1946

Second passive resistance campaign

In 1946, the Natal Indian Congress launched a second passive resistance campaign against the anti-Indian Land Act. It was led by Drs Naicker and Dadoo. Large numbers of Indian women played an active role. At the end of that campaign, almost 2 000 Indians were imprisoned for defying segregationist laws - 300 were women. Many other women actively supported the campaign by door-to-door fundraising, collecting food and offering childcare support.

A Passive Resistance Campaign meeting at Durban's Red Square. UWC-Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archives

Part 3. The fight against Apartheid - 1948

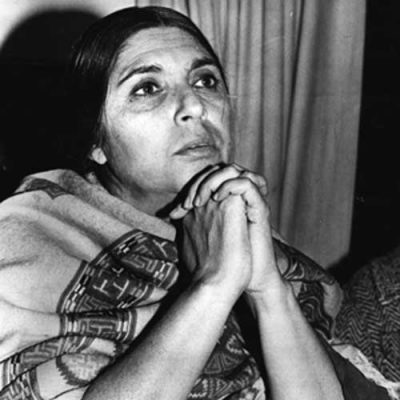

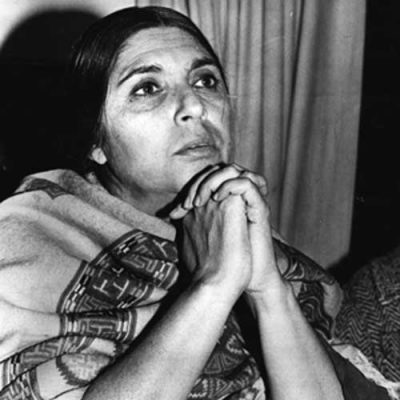

Fatima Meer, date unknown. Unknown

1952

Durban and District Women’s League

Women from the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) and the ANC established the Durban and District Women's League with Fatima Meer as President and Bertha Mkhize, then President of the ANCWL, serving as Chair. It was the first organisation with joint Indian and African membership – a union ahead of their parent bodies which still operated in consultation with each other but remained separate. The league actively engaged in the 1952 Campaign of Defiance of Unjust Laws.

Fatima Meer, date unknown. Unknown

Women protest the implementation of the passes, 22 December 1952. Cape Times

1952

Defiance Campaign

On 26 June 1952, the ANC launched the Defiance Campaign against six unjust apartheid laws:- the Group Areas Act; the Bantu Authorities Act; the Suppression of Communism Act and the Separate Representation of voters. Women from the ANCWL, the Congress of Democrats, the South African Indian Congress and allied organisations played a key role in the acts of defiance across the country. Over eight thousand people were arrested for participating in this campaign. The campaign ushered in a decade of the participation of both men and women in resisting apartheid.

“The Defiance Campaign was a very big thing. There were six laws in particular that we wanted to get them to stop because they were very bad laws ... Dr Moroka and Walter Sisulu sent a letter to the Prime Minister asking him to take back these acts, but when he said no, then we decided we must go ahead with the Defiance Campaign.”

-Francis Baard, trade unionist, organiser for the ANCWL

Women protest the implementation of the passes, 22 December 1952. Cape Times

Women protest the implementation of the passes, 22 December 1952. Cape Times

17 April 1954

The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) and the Women’s Charter

FEDSAW was launched as a multi-racial women's organisation and lobby group to address women’s issues more directly. The thrust for FEDSAW came from working class women who had been organised in the trade union movement, speaking in their own voice as activists on the ground. Its founders were the trade unionists Ray Alexander, Frances Baard and Florence Matomela, leader of the ANCWL in the Eastern Cape.

‘What Women Demand’, colloquially known as the Women’s Charter, was adopted at its launch. It set our goals for the emancipation of women and made two sets of practical demands - firstly, claims for equal legal rights with men and secondly, demands for services and amenities to ‘protect the mother and child’. As a political manifesto, the Charter strongly linked racial and gender struggles, arguing that the women’s struggle was part of a wider struggle for liberation in the struggle for a socialist state. There were limitations to the charter as the demands failed to challenge the deeply patriarchal attitudes to the role of women in society. The national struggle was still seen as the priority with the struggle for gender rights subordinated to that of race.

“We, the women of South Africa ... African, Indians, European and Coloured, hereby declare our aim of striving for the removal of all laws, regulations, conventions and customs that discriminate against us as women …

A Single Society: We women do not form a society separate from the men. There is only one society, and it is made up of both women and men. As women we share the problems and anxieties of our men, and join hands with them to remove social evils and obstacles to progress …

Freedom cannot be won for only one section or for the people as a whole as long as we women are in bondage.”

-From the Preamble of the Women’s Charter

Women protest the implementation of the passes, 22 December 1952. Cape Times

Members of the Black Sash organisation protest against apartheid laws outside Johannesburg City Hall, circa 1955 Jurgen Schadeberg / Getty Images

1955

Birth of the Black Sash

This organisation of white women was formed in response to a cynical ploy by the apartheid government to remove coloureds from the common voters' roll. It was initially called the Women's Defence of the Constitution League but came to be called the Black Sash because women protestors wore black sashes to indicate that they were in mourning for the National Party’s disregard for the constitution. At first, the organisation organised marches, petitions, overnight vigils and protest meetings and then later opened advice offices to provide information concerning the legal rights of black South Africans. These offices played a critical role in the fight against apartheid and provided an important space for white resistance. The Black Sash stood out in a context where few white women associated themselves with the national liberation struggle or joined the powerful women’s movements.

“The sight of white middle class women, well dressed, well spoken, well behaved - demonstrating against the government enraged many of its supporters … the women were exposed to verbal abuse and threats of violence. Not only were they defying the government, they were defying a set of unwritten rules about seeming and proper conduct for women.”

Cheryl Walker, author and activist

The Sash was reorganised in 1995 as a non-racial humanitarian organisation, working to 'make human rights real for all living in South Africa'.

Members of the Black Sash organisation protest against apartheid laws outside Johannesburg City Hall, circa 1955 Jurgen Schadeberg / Getty Images

Some of the delegates on the main platform of the Freedom Charter meeting at Kliptown. From left to right: a delegate from Port Elizabeth, E. P. Moretsele, President of the Transvaal branch of the ANC, Leon Levy, president of the SACTU, Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi and unknown. Museum Africa / Africa Media Online

1955

The Freedom Charter

After a consultative process involving 50 000 volunteers gathering ‘freedom demands’ of people residing in urban and rural areas, the Freedom Charter was adopted at Kliptown in Soweto. This statement of core principles of the Congress Alliance consisted of the ANC, the South African Indian Congress, the Congress of Democrats and the Coloured People’s Congress. Its opening demand, "The People Shall Govern!", was a clarion call throughout the decades.

FEDSAW drafted a document called ‘What Women Demand’ and most of these demands appeared in the final Charter - except for the demand for social amenities in the reserves as this would have endorsed the apartheid division of land in the rural areas. The committee of twelve that drafted the final text included several women such as Ruth First, Hilda Bernstein and Helen Joseph.. Beata Lipman wrote out the original version of the Charter.

Some of the delegates on the main platform of the Freedom Charter meeting at Kliptown. From left to right: a delegate from Port Elizabeth, E. P. Moretsele, President of the Transvaal branch of the ANC, Leon Levy, president of the SACTU, Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi and unknown. Museum Africa / Africa Media Online

Preparing to march, undated, circa 1955-1956. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

1950's

Lipasa! Amapasi - anti-pass demonstrations

In 1952, passes were again extended to African women leading to the imprisonment of thousands. Multiple protests erupted across the country. In 1954, 2 000 women were arrested in Johannesburg, 4 000 in Pretoria, 1 200 in Germiston, and 350 in Bethlehem. In 1955, 2 000 women marched to the Native Commission's office in Vereeniging.

“We women will never carry these passes. I appeal to you young Africans to come forward and fight. These passes make the road even narrower for us. We have seen unemployment, lack of accommodation and families broken because of passes. We have seen it with our men. Who will look after our children when we go to jail for not having a pass?”

-Dora Tamana, at an ANC Women’s League meeting in Langa in 1953

Preparing to march, undated, circa 1955-1956. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

The 1956 women’s march. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

9 August 1956

Women’s March to Pretoria

The anti-pass campaigns culminated in the now famous march of 20 000 women to the Union Buildings in Pretoria. The call-to-action flyers of the ANCWL and FEDSAW explained: “Passes mean prison; passes mean broken homes; passes mean suffering and misery for every African family in our country; passes are just another way in which the government makes slaves of the Africans; passes mean hunger and unemployment; passed are an insult ...”

Women arrived from all corners of South Africa. The march was led by Helen Joseph, Rahima Moosa, Lilian Ngoyi, and Sophie Williams-De Bruyn (only 18 at the time). They carried stacks of petitions to present to the then Prime Minister J.G. Strijdom. Women sang 'Wena Strijdom, wa'thinthabafazi, wathint'imbokotho uzokufa!' ('You Strijdom, you have touched the women, you have struck against rock, you will be crushed.) The women stood in silence for 30 minutes, many with babies on the back, whilst Strydom refused to accept the petitions. The march demonstrated the rise to political prominence of women in the struggle against apartheid and their great courage.

The 1956 women’s march. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

Lilian Ngoyi at the time of her second presidency of the ANC Women’s League, 1956. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

A national conference and a new national president

FEDSAW hosted its national conference the day before the march since many of its members had travelled from different parts of the country to participate. Lilian Masediba Ngoyi - who was the one who had knocked on President Strijdom’s door to present the petition - was elected national president. In her presidential address, she asked the audience why they had “heard of men shaking in their trousers, but who ever heard of a woman shaking in her skirt?” She urged women to continue protesting passes and to reach out to others especially in the rural areas and educate:

“Strijdom! Your government now preaches and practises cruel discrimination. It can pass the most cruel and barbaric laws, it can deport leaders and break homes and families, but it will never stop the women of Africa in their forward march to freedom during our lifetime!”

-Lilian Ngoyi’s warning to Prime Minister Strijdom

All four of the women leaders of the famous 1956 march in Pretoria came from the trade union movement. Lillian Ngoyi was a shop steward in the GWU; Helen Joseph represented the GWU’s medical aid; Sophie Williams was from the Textile Workers Union and Rahima Moosa was from the Food and Canning Workers Union.

Smaller women-led marches against the pass laws continued for the rest of the decade.

Lilian Ngoyi at the time of her second presidency of the ANC Women’s League, 1956. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

Women demonstrators held placards reading, ‘We stand by our leaders’ in support of the treason trialists, 19 December 1957. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

5 December 1956

Mass arrests and the Treason Trial

In a mass police swoop in the early hours of the morning, 156 political activists were arrested at dawn and charged with treason. The arrested were imprisoned in the Old Fort prison complex – now Constitutional Hill. Jacqueline (Jackie) Arenstein, Francis Baard, Ayesha Dawood, Lily Diederichs, Sonia Bunting, Ruth First, Bertha Gxowa, Helen Joseph, Florence Matomela, Ida Fiyo Mntwana, Lillian Ngoyi, Debi Singh and Annie Silinga were part of the group of women held in the Women’s Jail in separate sections for white and black prisoners. Ironically, their imprisonment gave them the opportunity to organise in a way that was difficult at the time.

“We didn't know why we were arrested until we went to court and met each other there. Hawu! And then we see there are so many of us! We listened to what the charges were … After a time we were released from prison although the case was still going on.”

-Francis Baard, trade unionist and women’s leader

There was mass action, mainly by women, outside the Drill Hall where the treason trialists first appeared. Women also arranged with local communities to ensure that food was brought to Old Fort prison where the treason trialists were being held.

Eventually the number of accused was whittled down to 31. After the longest Treason Trial in South African history, all were acquitted of treason in 1961. The judges agreed that the state had failed to prove the ANC or the Freedom Charter as communist.

Women demonstrators held placards reading, ‘We stand by our leaders’ in support of the treason trialists, 19 December 1957. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

Women protesting in Cato Manor over living conditions, government beer halls and passes for women, October 1959. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

1959

Mass Action in Umkhumbane

After World War II, a large section of Durban’s black population moved to the informal settlement of Umkhumbane on the ridges of Cato Manor. From 1958, the authorities began to implement plans to eradicate Cato Manor and transfer its population to the new township of KwaMashu. The police also started to issue passes to African women and to clamp down on illegal beer-brewing, forcing people to drink in government owned beer halls. Armed with sticks, Dorothy Nyembe led a group of women protestors who attacked the beer halls, chasing out the male customers and destroying the beer. The protest spread rapidly to other Durban beer halls and a successful beer boycott was launched. The police responded violently to the women protestors who bravely challenged them. The men of Umkhumbane responded with anger to the brutal treatment of the women.

“We do not want our husbands to go and spend their money in the Corporation Beerhalls. The Corporation encourages them to do this and we women suffer.”

-Gertrude Kweyana, women’s rights activist

Women protesting in Cato Manor over living conditions, government beer halls and passes for women, October 1959. Baileys African History Archive / Africa Media Online

THE EXISITNG TIMELINE STARTS BELOW HERE!!!!!!

Part 8. Writing the Constitution - 1994 - 1996

Members of Parliament and executives of the Women's League, Ntombi Shope, Thandi Modise and Bathabile Dlamini outside Parliament, August 1994.Roy Wigley

May 1994

Women at the heart of the new democracy

One of the striking features of South Africa’s first democratically elected Parliament, which doubled up as a Constitutional Assembly to draft South Africa’s final Constitution, was the prominence of women activists. One hundred and seventeen - over 27 percent - of the members were women. When Nelson Mandela was chosen by Parliament to be South Africa’s democratically elected President, he took with him from his old office into his new office two strong feminists Barbara Masakela and Jessie Duarte. The other forceful personality who had helped structure his office had been Frene Ginwala. In his first State of the Nation address, President Nelson Mandela proclaimed:

“It is vitally important that all structures of government, including the President himself, should understand fully that freedom cannot be achieved unless the women have been emancipated from all forms of oppression.”

The first democratic Parliament was praised for its gender-inclusivity:

“From being one of the world’s most sexist governments our new Parliament, with its 106-strong contingent of women, has emerged as one of the world’s most progressive. South Africa has moved from 141st place on the list of countries with women in Parliament, to seventh … With a jump from 2.7 per cent to 26.5 per cent, South African women are now better represented than their British and American counterparts.”

- The Sunday Times

Members of Parliament and executives of the Women's League, Ntombi Shope, Thandi Modise and Bathabile Dlamini outside Parliament, August 1994.Roy Wigley

June 1994

the Women’s Charter for effective equality

Although the broader political context had significantly changed after the elections and certain victories for women had been secured, the charter was still deemed to be an important intervention. Activists believed that it would represent a national consensus among women about the minimal demands of the women's movement and guide future legislative and policy interventions. After all, the charter campaign had already made an impact by enshrining gender equality and the possibility of affirmative action in the final Constitution. The original multiple demands of the charter were reduced to help consolidate and speed up the process. The final charter was presented to President Mandela in June 1994.

1996

The final Constitution prohibits gender discrimination

The first democratic Parliament doubled as a Constitutional Assembly (CA). The CA were given just two years to draft the text for the country’s first democratic Constitution. The National Coalition of Women continued to monitor the process. Skilled political activists together with technical experts and advisors and the broad women’s constituency helped to keep gender issues at the centre of the constitution-making process. The role of women in the constitution-making process was a continuation of the role they played in the struggle they waged throughout history.

“In the Constitutional Assembly, we directed our energies to those aspects women felt very strongly about. We opened doors for women to participate and speak as full delegates. I remember at some stage the media referred to us as the ‘broomstick ladies’. This did not deter us – we confronted patriarchy head-on. I remember some quarters argued that the equality clause should not be extended to rural women, who they claim were content with their subservient position. Yet women marched to the negotiations from rural areas to demand equality. Our position at the negotiations table was thus strengthened by the women’s movement and their activities outside the Constitutional Assembly. ”

- Mavivi Myakayaka-Manzini, ANC Theme Committee 4

1996

New legislation and institutions protecting women’s rights

The new government’s embrace of gender equality as a foundational principle of the new democracy, led to policies, programmes and laws that advanced women’s interests. Parliament moved quickly to introduce new legislation within a human rights framework to eradicate gender inequality, create substantive representation for women as well as to protect women in the domestic sphere. Public participation in the law-making process of the Assembly was now actively encouraged and there was a close and cooperative relationship between civil society and Parliament. New laws outlawed rape in marriage, promoted reproductive choices, offered protection from domestic violence for women, illegalised discrimination against women and promoted equal status under customary law.

“The presence within the state of women and men deeply committed to progress on gender equality was central to the achievement of many policies and laws … They retained relationships with women in civil society and were able to work in partnership to advance certain laws and policies … The fact that the Speaker had been a leading gender activist in the early 1990s, assisted these processes.”

- Catherine Albertyn, Professor of Law in ‘Towards Substantive Representation: Women and Politics in South Africa’

Part 9. Making the Constitution a lived reality - 1996 onwards

Taking root in day-to-day life

Despite women’s unprecedented participation in law-making and Parliament, and the newly entrenched human rights institutions and courts, enormous challenges remain for South Africa’s children and women. While some women have greater access to healthcare and resources, conditions on the ground remain hopelessly inadequate. Poverty is deepening. There are high rates of disease and infection amongst women.

For Catherine Albertyn, “From being one of the world’s most sexist governments our new Parliament, with its 106-strong contingent of women, has emerged as one of the world’s most progressive. South Africa has moved from 141st place on the list of countries with women in Parliament, to seventh … With a jump from 2.7 per cent to 26.5 per cent, South African women are now better represented than their British and American counterparts.”

Violence against women

The safety of women and children remains one of the most enormous challenges to be tackled. The country has one of the highest femicide rates in the world with more than 2 700 women and 1 000 children murdered in a single year. It is estimated that around 51% of women in South Africa have experienced abuse at the hands of their partners.

Women's Month in 2018 was marked by countrywide intersectional marches and pickets over violence again women, children and gender non-conforming people. It was organised by WomenProtestSA under the banner #thetotalshutdown. The rallying cry was "My body, not your crime scene" called on men to stop the abuse of women and children. "We have nothing to celebrate on 9 August," said the organisers of #TheTotalShutdown, referring to the annual commemoration of the women's march against apartheid passes.

Just over a year later, the harrowing rape and bludeoning to death of 19-year-old student, Uyinene Mrwetyana, by a post office worker at the local post office in Cape Town, tipped South Africans over the edge. Women poured onto the streets country-wide shouting ‘Am I next?’. The #IamNene ignited a movement. The President was asked to account and to make urgent interventions to stop the violence.

“We have been suffering in silence in our homes, scared and alone and we need to come together. We can't live like this anymore. We are not free. This is not a free South Africa.”

-Student protester, during a #IamNene

South Africa joined the global 16 Days of Activism for No Violence Against Women and Children campaign in 1998. Shamin Chibba

1996 onwards

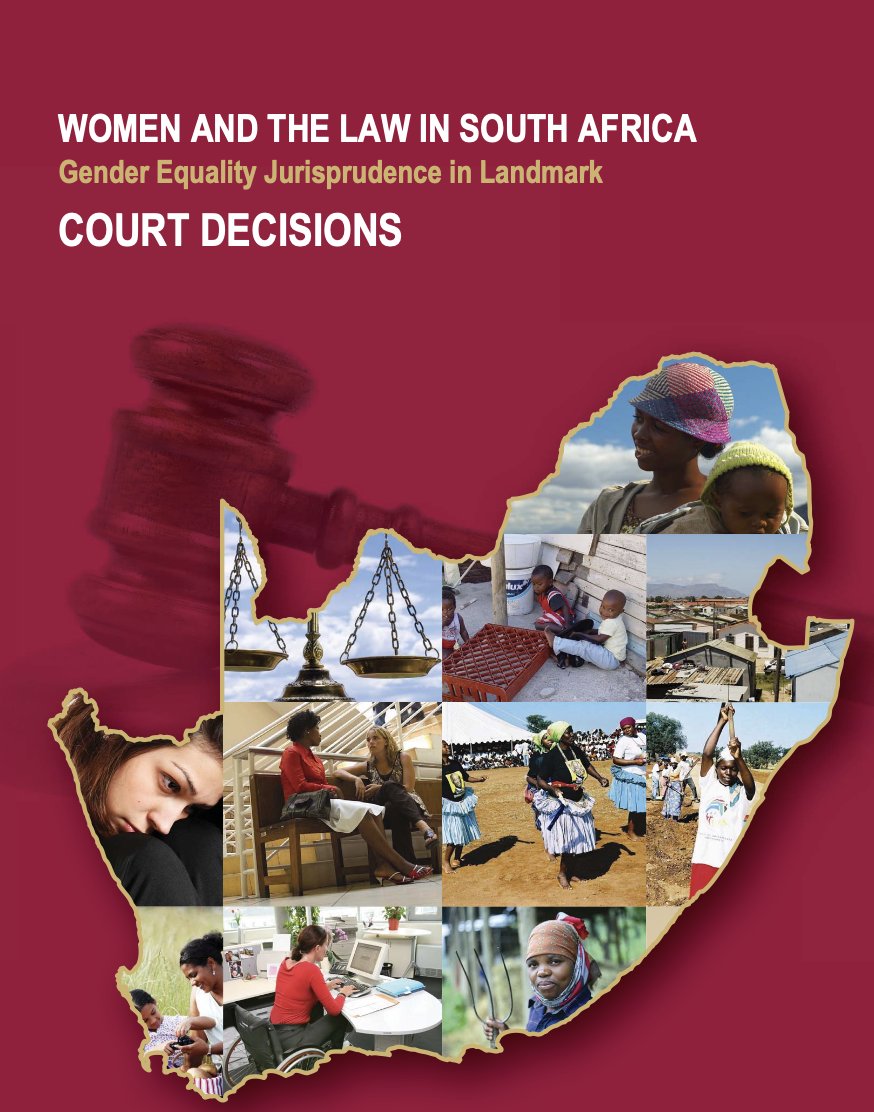

Victories for women at the Constitutional Court

The Constitutional Court has dealt with a number of cases linked to the struggle of women’s rights as human rights. Many cases illustrated the devastation caused by gender–based violence and have exposed inequalities in customary and divorce law. The judgements of the Constitutional Court have contributed to restoring the dignity of the women who are victims of inequality and of human rights violations.

South Africa joined the global 16 Days of Activism for No Violence Against Women and Children campaign in 1998. Shamin Chibba

The Struggle Continues

A formidable task remains in South Africa to ensure that women’s issues are raised and actively dealt with. The struggle for gender equality is currently being waged in both the public and private sphere. The high rates of femicide and rape in the private realm are echoed by violent rhetoric of sexism and patriarchy in the public domain. A new generation of African feminists are forging new paths outside of conventional political organisations. In a recent seminar, writer, activist and WISER Writing Fellow, Sisonke Msimang, was forthright in her critique of the ANC Women’s League:

“I have a huge problem with the ANCWL and the betrayal of the feminist vision that we fought for. Gender-based violence has become a-politicised. My generation of African feminists have taken to ‘direct action’ to politicise the GBV issue as a credible form of a new political grammar.”

The united actions by women to ensure women’s equality are diverse and a spate of new organisations have emerged over the last 20 years. South African women, who have played a leading role in resistance politics since the early 20th century - as evidenced by the example of Charlotte Maxeke and others in this timeline - continue to fight for gender and racial equality. The liberation and safety of women remains a critical issue in our country today.