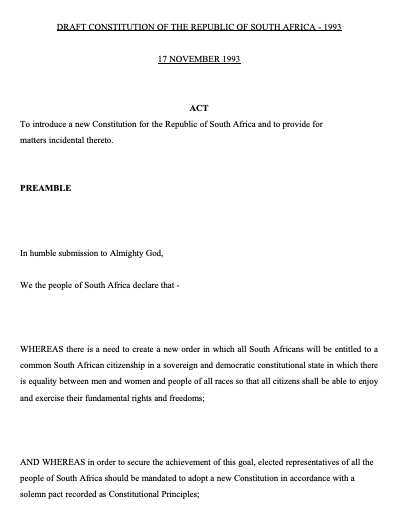

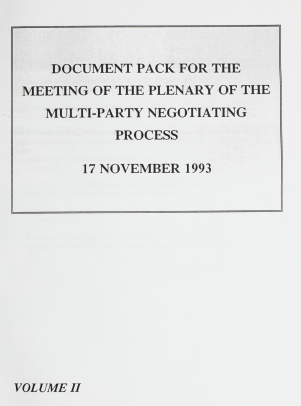

Events leading up to the adoption of the Interim Constitution

18 NOVEMBER 1993

National Archives and Records Service of South Africa

Sticking

points:

The stalemate around the death penalty and the right to life clause was one of the most difficult issues for negotiators. Leon Wessels, chief negotiator for the NP, helped break the deadlock. He suggested writing the right to life into the Constitution without any qualification, and leaving it open for the Constitutional Court to interpret this right. So, the term ‘constructive ambiguity’ was born. “Everyone can claim a victory, and the fight is postponed to another day and another forum,” said Wessels.

Final

agreement:

Other issues remained. While workmen were laying out the red carpet for the ceremony to ratify the Interim Constitution, De Klerk and Mandela personally became involved in negotiations. By 17 November – Cyril Ramaphosa’s birthday – Meyer jubilantly announced that the NP and the ANC “were in tandem on all remaining constitutional issues”. They now had to try desperately to persuade smaller parties – who felt that they were mere rubber stamps in the process – to go along with the deal. Final agreement was reached on 18 November. The technical team led by Arthur Chaskalson and Dikgang Moseneke worked round the clock to produce the final text

Success at last:

The Interim Constitution, which came into effect on 27 April 1994, would last until the new, democratically elected Parliament had performed its function, as not only the transitional legislative body, but also as the Constitutional Assembly responsible for drafting and delivering the final constitution.

The Interim

Constitution:

The Interim Constitution set in place a revolutionary principle in South Africa’s constitutional history, namely that the Interim Constitution would be the supreme law and that any law or act inconsistent with its provisions would be of no force. It provided a radical shift from apartheid rule to democratic elections, and also provided a historic bridge between the then still racist present and a multi-racial and equal future.

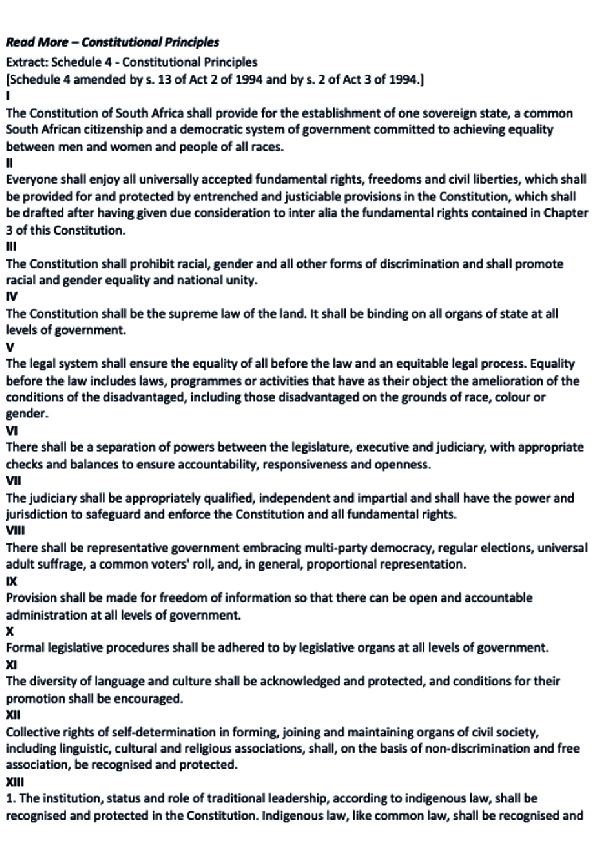

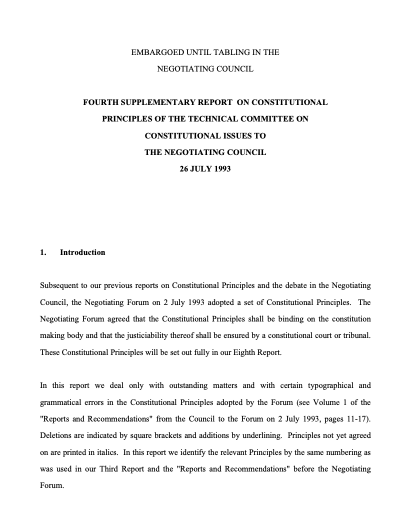

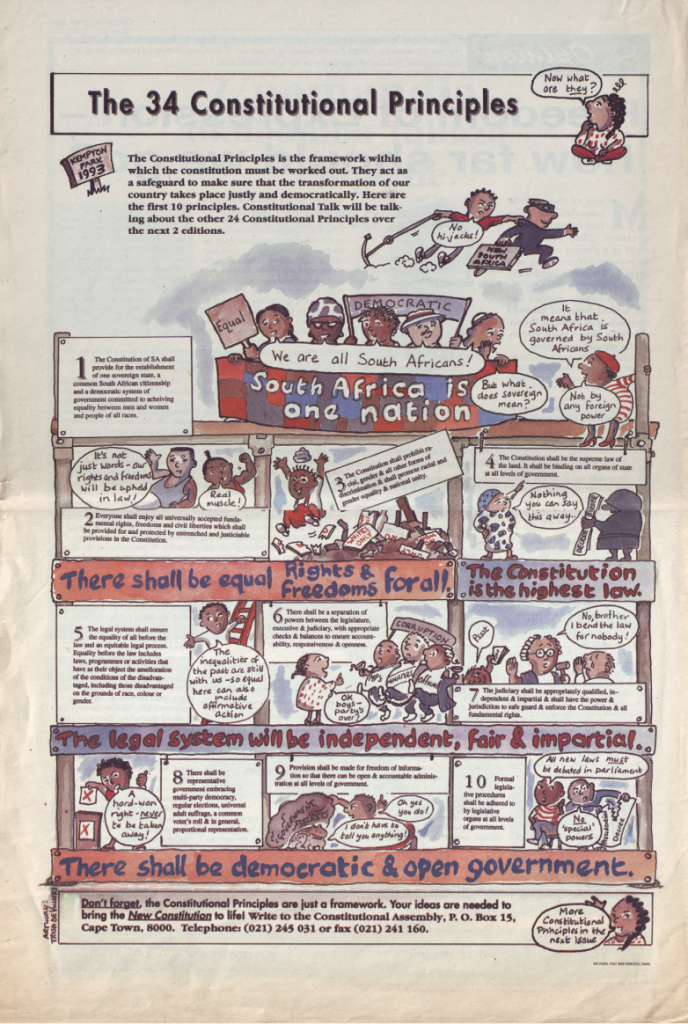

Constitutional

principles:

The Interim Constitution provided for the creation of the independent Constitutional Court to certify that the text of the final constitution adopted by the Constitutional Assembly complied with these Principles. According to a statement by the ANC, the Constitutional Principles should give “all participants the guarantee that they are not signing a blank constitutional cheque which could permit discrimination against themselves or any other section of the community in the future.” At the same time, they were not so detailed so as to pre-empt the work of the elected constitution-making body.

Going

forward:

The key issue now was to ensure free and fair elections to choose the members of the Constitutional Assembly who would draft the final Constitution in keeping with the Principles.

In their own words

“Women’s rights were integrated into the [Interim Constitution] in a way that few constitutions in the world had managed to achieve. It was thanks to a powerful movement of women across South Africa, mobilised behind skilled negotiators like Frene, Brigitte, Baleka, Thenjiwe and Mavivi, that women’s interests were secured in our Constitution.”

-Pregs Govender, then a leader of the Women’s National Coalition

“After the umpteenth late night, the small task team … got together, dog tired, to finally settle the stalemate situation surrounding the right on life and the death penalty … Joe Slovo remarked tiredly: ‘Years ago, in Lusaka, we had all the answers. Here we are now, tired to death, and we do not know how to go forward.’ Had the tool [of constructive ambiguity] not been available, the negotiators would still be at loggerheads today.”

–Leon Wessels, then Cabinet Minister and NP representative at the MPNP

“Ironic as it was, we had to rely on this very institution [the Tricameral Parliament] to bring an end to apartheid and usher in the new constitutional order.”

-Hassen Ebrahim, then National Coordinator of the ANC’s Negotiation Commission

“We would have liked to have seen something closer to the power-sharing in the Swiss or Belgium model. We would like more clearly defined rights for the regions and minorities. But we were satisfied that we had substantially succeeded in achieving the total package that I had spelled out as our bottom line during the referendum the year before.”

–FW de Klerk, then President of South Africa

“I knew from the very start that we wouldn’t fail. The NP was a formidable enemy. They were armed militarily and in terms of resources. But they were completely poverty stricken when it came to the will and determination to be free. They didn’t have it. We had it. Our people were united and they wanted to be free and that is what gave us strength … I knew that our victory was very certain. Nothing could stop this tidal wave towards freedom.”

-Cyril Ramaphosa, then ANC chief negotiator at the MPNP

“If ever there was a day that dawned with great promise, it is this day … If ever, in the troubled history of South African law-making, there was a document that could set the record straight, it is this measure. This is a moment to be cherished … This law determines the direction our country is to take. We are not merely witnessing great times. We are, indeed, writers of history and creators of the future.”

–Roelf Meyer, at the reading of the Interim Constitution Bill in Parliament, 17 December 1993

“Nobody will say that the [Interim] Constitution is a perfect one, but as one (often extremely critical) newspaper editor had said: ‘It’s the best that we have’. And although the contents can be improved upon, the process by which it was given birth will one day be acknowledged as one of the most extraordinary phenomena of modern-day constitutional history.”

-Dr Theuns Eloff, then Head of the Administration at the MPNP, in a personal reflection on the lessons learnt from CODESA and the MPNP, 1994