Events leading to the breakdown of CODESA and the launch of the Rolling Mass Action Campaign

MID - 1992

Graeme Williams

1992:

The year started with optimism. De Klerk had unexpectedly accepted the ANC’s demand for an interim government and achieving a climate favourable to free political participation. But, once again, there was a wide gulf between the two parties in understanding what this meant. As before, the ANC called for a rapid transition to an interim government, with CODESA deciding as little as possible on substantive issues. While it still enjoyed power, the government insisted on a long period of shared rule, with CODESA determining as much as possible.

The clashes in

Working Group 2:

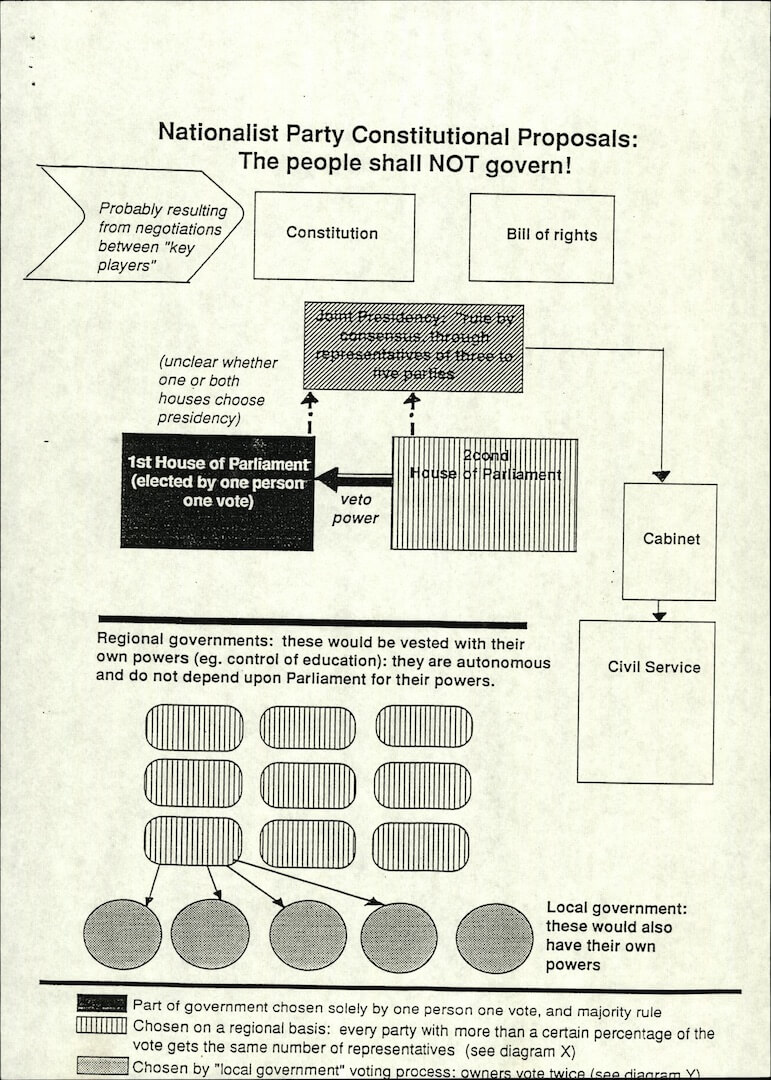

There was also a head-on collision in Working Group 2 around the structures and character of the South African state. Two completely different proposals were on the table. In its submission to this group, the government remained insistent that sustainable democratic structures should not be equated with ‘simple or unqualified majoritarian rule’. An elected majority would ‘swamp the constitution-making process and that is where negotiation will end’. As before, the ANC advocated for a non-racial democracy with an emancipatory Bill of Rights protecting all.

In response to

the stalemate:

Mandela laid out concrete and achievable conditions for the resumption of negotiations. A primary condition was the establishment of an interim government. (This was later transformed into a demand for a Transitional Executive Council that would oversee free and fair elections. The present government would continue and Parliament would vote itself out.) By March 1992, the progress of the working groups had halted.

The all-white

referendum:

In the meantime, conservative resistance to negotiations was hardening. De Klerk called for a referendum amongst white voters to test his mandate for change. The NP won an overwhelming victory in favour of continuing with negotiations. The NP returned to CODESA with renewed confidence and a misguided belief that they could retain power.

The second

plenary session:

On 15 and 16 May, CODESA 2 as it was known, deadlocked over the question of the special majorities required to adopt a final constitution. The government wanted important aspects of a new constitution to be settled or subject to change only by a 75% majority before any constitution-making body came into being, while the ANC insisted that only a popularly-elected constituent assembly with a relatively free hand to write a new constitution should make that decision. Ramaphosa announced the ANC’s withdrawal from Working Group 2. This meant the collapse of CODESA 2. The plenary received a report of failure on 16 May and then adjourned in a sombre spirit, never to be reconvened. Three days later, the ANC withdrew all constitutional compromises offered in Working Group 2.

The ANC–SACP–COSATU

Alliance:

While the politicians battled it out, the grassroots members of the alliance felt increasingly frustrated. For most people in townships across the country, there were no visible changes. How people lived, how laws were made, how the police and army operated, and who owned the land, were exactly as before. The release of political prisoners was proceeding very slowly with many still stuck on Robben Island. Moreover, most South Africans’ lives were now plagued by violence. Mandela repeatedly voiced his disbelief that a head of state, with a sophisticated security apparatus, could not do something to stop the violence engulfing the country.

Rolling

mass action:

The ANC-SACP-COSATU Alliance decided to demonstrate its power for change through the use of ‘rolling mass action’, in the hope that strikes and street demonstrations would force the NP to agree on an interim government and a non-racial democracy.

The first

stay-away:

The NP reacted with fury to what it believed was ‘euphemistically called mass action but was, in reality, physical confrontation’. The party believed that the ANC was “now making demands in a threatening manner in order to coerce the government into irresponsible concessions that could not be negotiated with the parties at CODESA”.

In their own words

“A one-man-one-vote election would put the cart before the horses by starting off with a simple majoritarian system which is actually the goal or desired outcome that some parties seek to achieve by the negotiations. On the basis of a majority-takes-all result, such an election would leapfrog the whole negotiating process – it would predetermine its outcome. The elected majority will swamp the constitution-making process and that is where negotiation will end. The government has no mandate to enter into a constitution-making process which has the effect of negating the negotiating process by imposing simple majoritarian decision-making.

“The majority is not the only interested party in constitution-making. A constitution is a structuring of the political process for all communities, and therefore requires a broader agreement than just a majority, so as to ensure its acceptance by all major political groupings and communities. There must be broad multi-party involvement in its acceptance.”

-Tabled by the South African government at CODESA Working Group 2

“So the NP proposed that it would be Mandela for six months, De Klerk for six months, and Buthelezi for six months, and the three of them would have to govern throughout by consensus. This would effectively have given the power of veto to each president, and instead of the constitution being the doorway to transformation, it would have become the barrier to change. It would have been a total disaster.”

–Albie Sachs, then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

“I was convinced at the time that the government was not negotiating in good faith and that in actual fact it was attempting to entrench certain unacceptable supposed constitutional principles … So I was happy that we actually had a breakdown … I think now there is almost consensus in the country … That there should be elections whereas at that particular point the government was still unclear.”

-Brigitte Mabandla, then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

“Both the NP and the ANC do not have sufficient confidence in arriving at a settlement through sheer negotiation and both are resorting to additional strategies – violence on the one hand and mass mobilisation on the other hand. The government wants to negotiate with a weakened ANC, and attempts to weaken the ANC on the ground by attacking its supporters, by creating the impression that it is not able to look after its people.”

–Fatima Meer, professor of sociology, author and activist

“That was the moment and that battle was won. It was won in the streets of South Africa, it was rolling mass action. Hundreds of thousands of people went out into the streets, and they were disciplined, they were organised.”

-Albie Sachs, then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

“Inkatha have been hard hit by the violence. More than a dozen of our local leadership and some of our senior leadership … Have been assassinated or badly wounded. Not enough arrests are being made.”

–Suzanne Vos, then representative of the IFP

“It’s easy to blame the police … I think the police have a ghastly time of it trying to keep peace in the townships. They’re put in an impossible position most of the time. They’re shot at. A lot of them have been killed. What police force in the world is killed off like they are?”

-Sheila Camerer, then Deputy Minister of Justice and NP negotiator at CODESA

“White minority rule and violence are two sides of the same coin. However much we may cry out against the violence and demand that the government stops it, they will be involved. For that reason, it has become an urgent priority to establish an interim government of national unity and also to have democratic elections to change the balance of forces.”

–Valli Moosa, then ANC negotiator at CODESA

“Ultimatum politics can’t be part of the negotiation process … The ANC simply do not seem able to adjust to a democratic political process … ANC rhetoric has degenerated into incitement to violence and hatred at grassroots level.”

-Roelf Meyer, then Minister of Constitutional Affairs and lead NP negotiator at CODESA

“This kind of war talk only increased the levels of violence. I pleaded that leaders on all sides start talking in conciliatory terms.”

–Dawie de Villiers, then Cape NP leader and negotiator at CODESA

“It was very sad indeed that there was a great deal of public recrimination between two very important organisations in the sight of all of the world. South Africa was ill served by those events … I hope the spirit of CODESA is coming back into our hearts.”

-Dr Zach de Beer, then leader of the Democratic Party

“I remember [an angry meeting] where Barbara Hogan and Tokyo Sexwale reported quite sharply on the violence in our township … The situation was indeed frightening. The response from this meeting was unanimous – we should take to the streets with a programme of rolling mass action. This was clearly going to raise the temperatures even more, but this was inevitable since it was evident that there was a direct linkage between the turmoil and conflict in our streets and at the negotiation table.”

–Hassen Ebrahim, then National Coordinator of the ANC’s Negotiation Commission