The Founding

Provisions

Chapter 1 of our Constitution immediately follows the Preamble and sets out the all-important values that underpin this document. The foundational principles of a united democratic state are human dignity and the achievement of equality; non-sexism and non-racialism; supremacy of the Constitution and the rule of law; and votes for all in an accountable multiparty democracy. They express the highest ideals for our constitutional democracy and implicitly require respect for key concepts such as Ubuntu and the separation of powers.

In essence, Chapter 1 signals the revolutionary shift from an oppressive and discriminatory legal and governing system to a new democratic order infused with humane values. Here you will gain a fresh understanding of the founding values of freedom, dignity and equality along with concepts of non-sexism and non-racialism, constitutional supremacy and the rule of law. You will see how the values underpinning our Constitution stand in stark contrast to those of the

apartheid era.

The Republic of South Africa:

The Republic of South Africa is one, sovereign, democratic state founded on the following values:

Human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms.

Non-racialism and non-sexism.

Supremacy of the constitution and the rule of law.

Universal adult suffrage, a national common voters roll, regular elections and a multi-party system of democratic government, to ensure accountability, responsiveness and openness.

Navigate the section

Some of our storytellers

Cyril Ramaphosa

RAY ALEXANDER

ALBERTINA SISULU

ALBIE SACHS

HELEN JOSEPH

JACOB ZUMA

MAVIVI MYAKAYAKA-MANZINI

AHMED KATHRADA

DIKGANG MOSENEKE

WHAT ARE THE FOUNDING PROVISIONS?

The opening words of the Preamble to the Constitution, ‘We, the people …’, signify the collective nature of past and present struggles in South Africa and also the collective action needed to bring about the transformed South Africa envisioned by the Constitution. The Preamble makes it clear too that our history informs our future. It emphasises that we, the people, have entered into a social compact to heal divisions of the past, free the potential of every person, and to build a South Africa that is united in its diversity.

Following the powerful language of the Preamble is Chapter 1 of the Constitution which sets out South Africa’s founding provisions. These include:

- The value statement of the Republic of South Africa (section 1)

- The endorsement of the supremacy of the Constitution (section 2)

- The affirmation of common citizenship (section 3)

- Symbolic matters such as the national anthem and flag (sections 4 and 5)

- Details about the official status of official languages and respect for indigenous languages (section 6)

As a testament to its significance in the Constitution, section 1 is very deeply entrenched and difficult to amend. Section 74(1)(a) of the Constitution states that the founding values in the Constitution can only be amended with a supporting vote of 75% of the members of the National Assembly plus a supporting vote of 6 provinces in the National Council of Provinces. Whilst amending the Bill of Rights has a less difficult requirement of a supporting vote of two-thirds (66%) by the National Assembly and 6 provinces in the National Council of Provinces.

Section 1 - The value statement

The first of the founding provisions in the Constitution defines South Africa as a state founded on the values of ‘human dignity, the achievement of equality and the advancement of human rights and freedoms’.

Given our painful history, it was self-evident that human dignity is a fundamental value that permeates all rights in the interpretation

of rights.

Enver Surty

then African National Congress member of Parliament

1.1 Human dignity / Menswaardigheid / IsiThunzi SobuNtu

Under Apartheid

Apartheid laws and practices were premised on the belief that black South Africans were inferior and should be treated as subordinate to the white population. For centuries these laws had stripped black people of their dignity. The apartheid government strengthened all forms of discrimination and racism that had already been in practice under a succession of colonial governments and they codified and legalised inequality. For example, the Population Registration Act of 1950 required all South Africans to register and be classified as either ‘white’, ‘coloured’, ‘Indian’ or ‘Bantu’. The Group Areas Act of 1950 determined where people should live and work and which places they could move to or visit. The Abolition of Passes and Coordination of Documents Act of 1952 required all black South African males to carry passes. In 1956, the law was amended to embrace black South African women as well.

Migrant labour, exploitation, depressed living conditions, displacement and forced subjugation, collectively stripped black South Africans of their dignity. The full might of the state was often brought to bear on people who resisted this ideology and its deplorable consequences through legislation designed to silence anti-apartheid activists. Apartheid attacked not only race but class, gender and sexual orientation.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Human dignity expresses the belief that every person has intrinsic worth. Respect for the dignity of all human beings is particularly important in South Africa where for so long, the system of apartheid – and colonialism before it – denied a common humanity, thereby diminishing the dignity of all South Africans. The Constitution rejects this past and affirms the equal worth of all South Africans. Recognition and protection of human dignity is the criterion of South Africa’s democracy and is fundamental to the Constitution.

By placing human dignity at the epicentre of our human rights architecture and underpinning it with commitments to personal and social equality and freedom, the rights acquire a higher standing than merely that of a set of restraints upon the state.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

Dignity is the source of personal rights, such as the right to a name and the right to physical, mental and moral integrity. Dignity also forms the basis of a person’s innate rights to freedom and equality, life and privacy. The Constitution has been designed to protect and advance the rights and dignity of the vulnerable in our society, rather than to preserve the privileges of the powerful. Dignity underpins the Bill of Rights as a whole and for example amongst many other functions, gives protection against gender violence in the private domain. It provides for strong rights for children and it guarantees a right to fair labour practices.

We understood that dignity was the overarching right – the essence of the society we hoped to create – and that dignity first had to be expressed in equality.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

In Practice

The Constitutional Court has made its pronouncements on the meaning of dignity clear in many judgments. In S v Makwanyane and Another, the judgment which abolished the death penalty, Justice O’Regan stated that “without dignity, human life is substantially diminished”. She argued that establishing the founding constitutional value of human dignity acknowledges the intrinsic worth of human beings who are entitled to be treated as worthy of respect and concern.

In Freedom of Religion South Africa v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Others, the Constitutional Court had to decide whether reasonable and moderate chastisement of children by their parents was constitutional. The Constitutional Court held that moderate and reasonable chastisement impairs the dignity of a child and thus limits her or his section 10 constitutional right.

1.2 Equality / Ukulingana / Ku ringana

Under Apartheid

Inequality was the very basis of the apartheid system. The political and legal systems promoted the socio-economic standing of white people at the expense of black people and legalised inequality. Over the decades, thousands of resistance movements called for equality and wrote this demand into their constitutions and programmes of action. In present day South Africa, the deep scars of inequality can be seen in all spheres of life – for example, in access to quality healthcare, work, education and property.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

One of our Constitution’s objectives is the transformation of our society from a grossly unequal society to one in which there is equality between men and women and people of all races. Equality was the first fundamental right that the drafters agreed to. Non-sexism was put on a par with non-racism as a foundational value.

Section 9 of the Constitution sets out all the components of the right to equality. Section 9(1) provides that everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law. Section 9(3) proclaims that the state may not unfairly discriminate against anyone on the grounds of race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth. Discrimination on unspecified grounds can also violate the right to equality. There will be discrimination on an unspecified ground if it is based on attributes or characteristics which have the potential to impair the fundamental dignity of persons as human beings, or to affect them adversely in a comparably serious manner. Equality and the prohibition of unfair discrimination are fundamental to the guarantee of human dignity.

Equality means that all people should have equal opportunity to achieve their potential. The Constitution emphasises that the decades of systematic racial discrimination entrenched by apartheid cannot be eliminated without positive action being taken to achieve that result. Because of a history of dispossession and inequality, equality cannot always be achieved by treating everyone the same. The right strives to achieve genuine equality by ensuring that all members of society have equal opportunities. The Constitution requires us to look at the impact of discrimination on people to see whether it promotes or impedes the achievement of equality and opportunity.

We crafted the equality provision that addressed both the personal and social aspects of equality, with a full suite of social and economic rights, from basic human survival needs for food, shelter and care, to education and labour rights, laying down principles through which people could exercise their freedoms.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

In Practice

The Constitutional Court has expanded on the meaning of equality in a number of judgments. For example, in National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice & Others, the Constitutional Court held that the sodomy laws that criminalised sexual activity between consenting males violated the right to equality. The Constitutional Court has repeatedly referred to South Africa’s unjust history and the need to remove discriminatory laws. The Court has said the following:

Our history is of particular relevance to the concept of equality. The policy of apartheid, in law and in fact, systematically discriminated against black people in all aspects of social life. Black people were prevented from becoming owners of property or even residing in areas classified as ‘white’, which constituted nearly 90% of the landmass of South Africa; senior jobs and access to established schools and universities were denied to them; civic amenities, including transport systems, public parks, libraries and many shops were also closed to black people. Instead, separate and inferior facilities were provided. The deep scars of this appalling programme are still visible in our society. It is in the light of that history and the enduring legacy that it bequeathed that the equality clause needs to be interpreted.

The Constitutional Court

Brink v Kitshoff N.O.

1.3. Freedom / Inkululeko nokuphepha komuntu / Mbofholowo na tsireledzo ya muthu

Under Apartheid

Many laws were passed by the apartheid government (and its predecessors) to curtail the freedom of black people. Two of the most oppressive apartheid laws were specifically aimed at controlling the free movement of people, namely, the Group Areas Act of 1950 and the Natives (Abolition of Passes and Co-ordination of Documents) Act of 1952, commonly known as the ‘Pass Laws Act’ of 1952. According to Helen Joseph, a leading anti-apartheid activist, “LIPASA! AMAPASI!” would become “the most hated of all words … the badge of cold slavery with all its ugly implications … ” The impact of this law is summed up in the Federation of South African Women’s (FEDSAW) 1956 petition delivered to then Prime Minister Strijdom:

For hundreds of years, the African people have suffered under the bitterest law of all – the pass law, which has brought untold suffering to every African family. Raids, arrests, loss of pay, long hours at the pass office, weeks in cells awaiting trial, forced farm labour – these are what the pass laws have brought to African men: punishment and misery, not for a crime but for the lack of a pass.

We African women know too well the effects of this pass law on our homes, our children. Your Government proclaims aloud at home and abroad that the pass laws have been abolished, but we know that this is not true for our husbands, our brothers and our sons are still being arrested, thousands every day, under those pass laws. It is only the name which has changed. The reference book and the pass are one.

FEDSAW Petition, 1956

Black South Africans fiercely resisted these and the other laws that curbed their freedom. Undeterred, the apartheid State clamped down. Between 1916 and 1984, about 1 770 000 black South Africans were arrested under a battery of pass laws and influx control legislation. Campaigns and strikes organised and driven by political organisations, individual acts of defiance and single litigants all challenged apartheid laws. This was illustrated by the 1975 Komani NO v Bantu Affairs Administration Board, and 1983 Rikhotso v East Rand Administrator Board landmark cases which successfully challenged the Group Areas Act and pass laws respectively. Many people were arrested, imprisoned, detained, placed under house arrest, forced into exile and some killed protesting against such legislation as the pass law regulations, influx control and the permit system.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Freedom in the Constitution is in one respect about establishing a society in which persons are free to develop their personalities and skills, to seek out their own ultimate fulfilment, to fulfil their own humanness and to question all received wisdom without undue limitations placed on them by the government. These freedoms are fundamental to the guarantee of human dignity.

Our definition of freedom of the individual must be instructed by the fundamental objective to restore the human dignity of each and every South African. This requires that we speak not only of political freedoms. My government’s commitment to create a people-centred society of liberty binds us to the pursuit of the goals of freedom from want, freedom from hunger, freedom from deprivation, freedom from ignorance, freedom from suppression and freedom from fear.

Nelson Mandela

then President of South Africa

There is no unqualified ‘right to freedom’. Instead, specific instances of freedom are protected. The freedoms protected by the Bill of Rights are enshrined in a number of rights such as the freedom and security of the person (section 12), freedom of religion, belief and opinion (section 15) and freedom of expression (section 16).

Freedom, the third essential element in a culture of human rights, is in turn articulated in a suite of seven individually expressed rights. Some of them – security of the person, privacy, opinion, expression – function at the personal level, while others – assembly, association, political participation – are exercised socially.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

In Practice

In the Constitutional Court judgment, Ferreira v Levin NO & Others, the Constitutional Court defined freedom as “the right of individuals not to have obstacles to possible choices and activities’ placed in their way by … the State … individual freedom must be generously defined.”placed in their way by … the State … individual freedom must be generously defined.”

In S v Mamabolo, Russell Mamabolo criticized the decision of a High Court judge to grant bail pending appeal to Eugene Terre Blanche, the leader of a right-wing group, the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging. In a newspaper article Mamabolo said that the judge “had made a mistake”. The judge issued an order calling on Mamabolo to appear before him to explain on what basis he had made a mistake. The judge held that Mamabolo’s statement was a scandalous comment which impugned on the integrity of the court and that it was not the exercise of the right of freedom of speech, and convicted Mamabolo of contempt of court. Mamabolo challenged this conviction. In a judgment that enhanced freedom of speech, the Constitutional Court found that the contempt of court conviction in this case was unconstitutional and an unjustifiable limitation to the right to freedom of expression.

1.4 Non-racialism / Nierassigheid / go sa kgethololeng ka bomorafe

Under Apartheid

The system of colonialism and then apartheid subordinated black people in South Africa. They were systematically stripped of citizenship rights as well as political and socio-economic rights. The apartheid government enforced a plethora of legislation that collectively institutionalised racism in all spheres of life. Race became a key marker and classificatory system embraced by the apartheid government to control the lives of all South Africans.

In response, anti-apartheid activists supported by a range of political organisations and movements, came to embrace non-racialism as a driving force in their resistance. Albie Sachs explains the meaning of ‘non-racialism’ from his point of view:

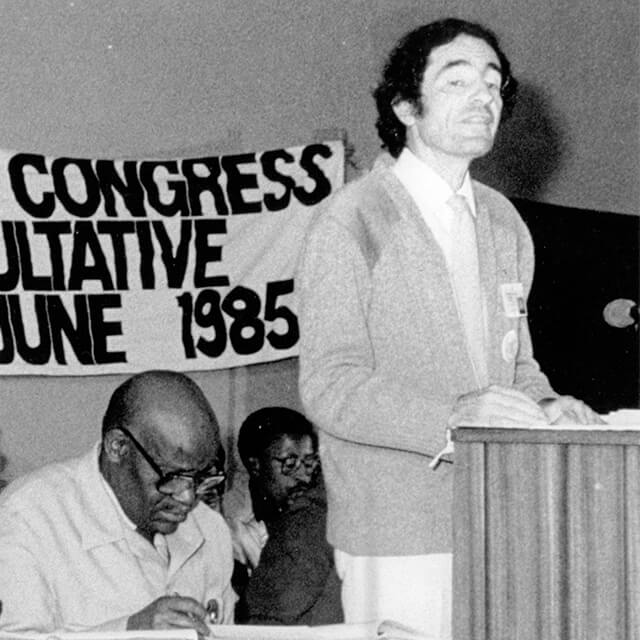

Non-racialism does not just mean the absence of racism – that’s empty. Non racialism means the elimination of all the apartheid barriers, in terms of access to government, in terms of freedom to move, so that everyone can feel that this is their country. But it doesn’t describe the quality and personality of the country and people. That is not a non-something — that is a something. It is a South African personality that is being constructed.

Albie Sachs

then lawyer and anti-apartheid activist, 1985

The demand for a non-racial South Africa united a wide range of resistance movements. In the late 1980s, the ever-broadening struggle for a non-racial future, known simply as the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM), gathered extraordinary momentum. In all its campaigns, the call for non-racialism was manifest, whether in the composition of crowds or the articulation of aims. The following quotes illuminate calls for non-racialism across the political spectrum in the broader anti-apartheid struggle:

The resilience of our people and their determination to be free defies all odds: it is an unshakeable belief in democracy and non-racialism which motivates them to forge ahead.

Message from the Youth Leadership

issued from underground by South African Youth Congress (SAYCO)

What is the unifying perspective of the Mass Democratic Movement? It is, simply, to turn our country into a non-racial, democratic and united South Africa.

Titus Mafolo

then spokesperson for the MDM

The ’70s saw the collapse of the partition state, the ’80s saw the shift to the integrated state — the ’90s will see the battle for the non-racial democratic state.

Frederik van Zyl Slabbert

then director of policy and planning for Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA)

In the face of the severest persecution and repression imaginable — banning, torture, imprisonment, maiming, killing — the ANC has a proud and incomparable record of consistently maintaining its policy of non-racialism.

Ahmed Kathrada

THEN HIGH COMMAND OF THE ANC'S MILITARY WING, UMKHONTO WE SIZWE

In Nelson Mandela’s first public address upon his release from prison in February 1990, his call was for a united, democratic and non-racial South Africa:

We call upon our white compatriots to join us in the shaping of a new South Africa — the freedom movement is a political home for you, too. Universal suffrage on a common voters’ roll in a united, democratic and non-racial South Africa is the only way to peace and racial harmony.

Nelson Mandela

Upon his release from prison in February 1990

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

This ideal of non-racism was enshrined first in the Interim Constitution and then in the final Constitution.

Fundamentally non-racialism has to be learned and taught. The alternative is to assume that it is something innate, instinctive, a thread that has always been there – and is unbreakable. But non-racialism is not an intrinsic part of political consciousness … each new generation must study it and learn it for themselves. It is a breakable thread. It does not arise naturally out of South African life, as does African nationalism. It has to be learned by teaching, by experience, by example.

Hilda Bernstein

then member of the Communist Party

In Practice

In the South African Revenue Services v Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration and Others (2016), the Constitutional Court dealt with a matter where the racist term ‘“kaffir’” was used in the workplace. The Constitutional Court held that there should be no neutralisation of racism and that courts must take a firm and unapologetic approach to fulfil their constitutional obligation and to eradicate racism and its tendencies.

Despite the strong ideological tradition of non-racialism in the liberation struggle in South Africa and the centrality of the founding principle of non-racialism in the final Constitution, the legacy of racism remains all too evident in South Africa today. There is increasingly vocal scepticism of non-racialism simply being synonymous with colour blindness with pointed questioning of exactly who this ‘blind’ non-racialism might be serving in contemporary South Africa. Recent activism on South African university campuses highlights dissatisfaction with the term non-racialism. One commentator on the #IAmStellenbosch campaign commented: “Non-racialism is the new magic cloak whiteness wears to disguise itself.”

1.5 Non-sexism / ukungabandlululi ngobulili / Kungabi khona kwelubandlululo ngokwebulili

Under Apartheid

Apartheid not only instituted racist laws against all black South Africans, but also passed laws that specifically discriminated against black women who occupied the lowest place in the apartheid hierarchy. As early as 1893, African women experienced the humiliation of being regarded as minors, irrespective of age or marital status; the marginalisation entrenched by the migrant labour system and the indignity of carrying a pass.

Indian and coloured women fared only slightly better. They were excluded from the migrant labour system and allowed to move freely to secure employment opportunities. They were, however, also subject to the apartheid system’s racial allocation of resources such as policies of job reservation and access to educational facilities.

White women, as members of the most favoured racial group in the apartheid racial hierarchy, were in the most advantageous position. This did not mean, however, that white women escaped all of the disadvantages and discrimination suffered by all women in a patriarchal society like South Africa. They were only given the right to vote in 1930, for example. In the private sphere, white women were subjected to highly patriarchal and sexist attitudes within their own communities. The system of racialised sexual subordination under apartheid and the violence to which women were subjected as a result, only began to emerge as an issue of national concern during the dying days of apartheid – perhaps because during the apartheid years, all women were considered

second-class citizens.

The energies of women’s organisations were directed toward achieving equality through the eradication of the racism of apartheid and not, at least initially, through the elimination of sexist, patriarchal structures. Most of the major women’s organisations in the pre-1990 period were secondary in status to the liberation movements or they operated with the specific purpose of opposing apartheid, although they did also articulate issues specific to women. Albertina Sisulu reflected on her role in the struggle for women’s rights within the broader context of national liberation:

In 1944, I joined the ANC Women’s League, which was formed to ensure that women’s issues could be discussed and acted on. It recognised the fact that men did not understand the problems that affected women directly such as children, maternity grants, education, cost of living.

Because some women were afraid to associate with the ANC but wanted to promote these kinds of concerns, we formed the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW). One of our first major campaigns was the anti-pass protest, resulting in the massive women’s march on the Union Buildings in Pretoria. The men were elated because of the number of women we were able to mobilise, but less happy when we promoted specific issues concerning the rights of women in relation to men.

Albertina Sisulu

Then anti-apartheid and women’s rights activist

Ray Alexander similarly believed that the struggle for women’s rights could not be divorced from national liberation and the struggle for equality in all spheres:

The lives of women, like those of men, are influenced and moulded by race, class and other factors. To suggest that these factors can be ignored in promoting the rights of women is tantamount to suggesting that the divide between rich and poor women, or black and white women can be glossed over or even accepted. I believe in equality between women and men, I believe in economic and racial equality between all people. The one cannot be separated from the other.

Ray Alexander

Then anti - apartheid and women’s rights activist

The Women’s National Coalition, formally launched in April 1992, was a historic moment in drawing together women from different class, racial and political backgrounds and pushing for women’s rights. While the coalition was developing the Women’s Charter, it also was engaged in lobbying in relation to discussions at the multiparty negotiations. The coalition identified three key areas of intervention: women’s inclusion on negotiating teams; the inclusion of non-sexism in the Constitutional Principles; and the inclusion of an equality clause in the Constitution that would supersede the right to custom and tradition.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

The Constitution uniquely contains the words non-racialism and non-sexism. Non-sexism is expressly identified as being on a par with non-racism as a foundational value of the Constitution. This means that women, who were previously oppressed due to their gender, are entitled to ‘full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms’ under a democracy.

The term ‘non-sexism’ is mentioned in the first document to be produced by CODESA. But when the technical team responsible for drafting the text of the Interim Constitution were finished, the term was not there despite a recommendation made by the Gender Advisory Committee at the Multi-Party Negotiating Process (MPNP). The first draft of the Constitutional Principles contained in the final Interim Constitution of November 1993, omitted all explicit reference to non-sexism. The coalition sent a submission to the MPNP asking for the explicit inclusion of the principle of non-sexism and prohibiting gender discrimination along with racial discrimination. The technical committee incorporated the demand to prohibit gender discrimination but excluded non-sexism from the Constitutional Principles, arguing that this was implied by the general terms of the Principles. Even the ANC wavered on the importance of explicitly including non-sexism, although the language of its own party documents had, since the declaration of 2 May 1990, emphasised a “non-racial, non-sexist democracy.” Jacob Zuma, acknowledged in other contexts that the inclusion of the qualifier was important:

Why not simply say democracy? Would that not automatically include being non-racial and non-sexist? The answer is NO … It is important for us to underline and emphasise that in the new South Africa our democracy will be inclusive. It will not define the concept or participation in the democratic process in terms of race, nor will it exclude any group. It is for similar reasons that we felt it necessary to describe the new South Africa as non-sexist. The truth is that ours is a very sexist society and women have been excluded from full participation.

Jacob Zuma

then Chairperson of the ANC for the Southern Natal region

This sentiment finally prevailed. The debate on the non-sexism clause was reopened when the Interim Constitution was presented to the Constitutional Assembly, and this time women members of Parliament successfully argued for the inclusion of the principle of non-sexism.

In the Constitutional Assembly we directed our energies to those aspects women felt very strongly about. We opened doors for women to participate and speak as full delegates. I remember at some stage the media referred to us as the ‘broomstick ladies’. This did not deter us – we confronted patriarchy head-on at the constitutional negotiations. I remember some quarters argued that the equality clause should not be extended to rural women, who they claim were content with their subservient position. Yet women marched to the negotiations from rural areas to demand equality. Our position at the negotiations table was thus strengthened by the women’s movement and their activities outside the Constitutional Assembly.

Mavivi Myakayaka Manzini

then member of the Constitutional Assembly

In Practice

The Constitutional Court has dealt with a number of matters that have concerned redressing the sexism of the past. In Hugo v. President of the Republic of South Africa and Others, the Constitutional Court considered the constitutionality of an executive order signed by President Nelson Mandela, that sought to pardon all mothers in prison on 10 May 1994, with minor children under the age of [twelve] 12 years.

This executive order was challenged by a male prisoner who argued that it unfairly discriminated against him on the grounds of sex or gender, and indirectly against his son – just because the latter’s incarcerated parent was not female. The Court acknowledged the generalisation about women bearing the greater proportion of the burden of childrearing and how that has historically been used to justify the unequal treatment of women. The Constitutional Court concluded that no public benefit would be gained by releasing fathers because they were not the primary caretakers of children.

The Court has acknowledged that there is a sexual division of labour that burdens women with childcare and household responsibilities. And it has also recognised that the gendered form of poverty results when families break down and women are usually left with the responsibility for children and consequent greater financial difficulties.

1.6 Rule of law / Umthetho womthetho / oppergesag van die reg

Under Apartheid

Prior to 1994, the rule of law in South Africa was in fact the rule by law. Parliament was the supreme law-making authority and therefore rule by law meant that the content of the law – whether it was just and fair – was of no concern. What was of concern was that there were laws in place that maintained structure in society even if that structure was devoid of justice, equality and freedom.

The apartheid legal system was a prime example of legal positivism that had gone wrong. A legal system that trampled on fundamental rights and freedoms, that was devoid of normative content, that was unjust; and yet its legal theorist still claimed that to be in accordance with the rule of law. Apartheid judges too escaped from their judicial consciences by claiming a duty to enforce unjust laws. In effect, rule of law had been replaced with rule by law. The law authorised racism, inequality, indignity and social and economic exclusion.

Former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke

in the Helen Suzman Memorial lecture, 2016

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

The rule of law requires the equality of all South Africans before the law, and also that laws are to be stated in a clear and understandable manner. The rule of law requires that public power should be exercised in compliance with the Constitution and within the boundaries set by the Constitution as the supreme law of the land.

It further requires the rational and non-arbitrary exercise of power. The rule of law ‘refers to a wider concept and deeper principle: fundamental fairness linked with the founding values of accountability, openness and responsibility’. Section 1(c) of the Constitution lists ‘supremacy of the Constitution and the rule of law’ among the founding values of the democratic South African state. Constitutional supremacy replaced parliamentary sovereignty and the supremacy of the Constitution entrenched the principle of judicial review, which meant the courts – unlike under apartheid – have the power to determine that the content of the law is constitutional. Because the Constitution, and not Parliament, is now supreme, the courts have the power to declare that law and conduct that is inconsistent with the rule of law as embodied by the Constitution, is invalid (in terms of section 172 of the Constitution).

In Practice

In the judgment of Dawood v Shalabi and Thomas v Minister of Home Affairs, the Constitutional Court noted that the rule of law required laws to be stated in a clear and accessible manner. In Chief Lesapo v North West Agricultural Bank, the Constitutional Court held that the principle against vigilantism and self-help is an aspect of the rule of law.

In respect of the importance of the public’s participation in law-making the Constitutional Court has made import pronouncements on this issue including

the following:

Public participation in the law-making process is one of the means of ensuring that legislation is both informed and responsive. If legislation is infused with a degree of openness and participation, this will minimise dangers of arbitrariness and irrationality in the formulation of legislation. The objective in involving the public in the law-making process is to ensure that the legislators are aware of the concerns of the public. And if legislators are aware of those concerns, this will promote the legitimacy, and thus the acceptance, of the legislation. This not only improves the quality of the law-making process, but it also serves as an important principle that government should be open, accessible, accountable and responsive. And this enhances our democracy.

Justice Sandile Ngcobo

in the judgment of Doctors for Life International v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others, 2006

1.7 Universal adult suffrage

Under Apartheid

Universal adult suffrage is the right of citizens in a given society, who are entitled to vote in an election, to elect a government to represent them. Usually, the only restrictions apply to people under a certain age and non-citizens. For most of the time that apartheid was in force, only people classified as ‘white’ were allowed to vote, meaning that only white voters were represented in Parliament.

The 1983 Constitution created a tricameral legislature with three parliamentary chambers: the House of Assembly (white representatives); the House of Representatives (coloured representatives); and the House of Delegates (Indian representatives). It allotted voting power to whites, Indians and coloureds, in a ratio of 4:2:1 respectively but gave no representation to black people. This system was largely rejected. The United Democratic Front (UDF) was initially set up to fight against the new ‘insult’ of the 1983 Constitution and its tricameral Parliament calling it ‘apartheid in disguise’. 90 000 students and 90 000 miners went on strike against the implementation of the tricameral Parliament.

Until 1994, black people in South Africa were denied citizenship rights including most civil, economic and political rights and the all-important and all-encompassing right to vote. In 1994, with the end of apartheid and the election of a new Government, the new Interim Constitution introduced non-racial democracy and declared that all men and women were equal. All eligible South Africans were able to cast their vote for the first time on 27 April 1994 to mark the end of apartheid rule and establish a new constitutional order.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Section 1 of the 1996 Constitution provides that two of the core values on which South Africa is founded, is ‘universal adult suffrage’ and ‘a national common voters roll’. It goes on to guarantee that ‘every adult citizen has the right . . . to vote in elections for any legislative body established in terms of the Constitution and to do so in secret’. However, democracy is about more than just elections. The Constitution gives each South African citizen the right and opportunity to get involved, during elections (representative democracy) and beyond (participatory democracy), in deciding upon matters that concern them or the society they live in, and to hold authorities to account.

The participation by the public on a continuous basis provides vitality to the functioning of representative democracy. It encourages citizens of the country to be actively involved in public affairs, identify themselves with the institutions of government and become familiar with the laws as they are made. Universal adult suffrage and all elements of a participatory democracy allows the voices of all to be heard and taken account of. Being able to vote for one’s own representatives in Parliament strengthens the legitimacy of legislation in the eyes of the people.

While the Interim Constitution was a politically negotiated product, the 1996 Constitution was not. The 1996 Constitution was produced through extensive public involvement, facilitated by the first democratic Parliament. It is important for the health of democracy for this tradition of public involvement in state affairs to be sustained beyond elections.

In some meaningful, more than merely symbolic sense, a mobilised and engaged grass roots is another ‘branch’ of government. It is the people exercising their power and voice in the purest form.

Professor Karl E. Klare

Northeastern University, Boston, USA

In Practice

In the Constitutional Court judgment, August v Electoral Commission, the Court recognised the prisoners’ right to vote, and consequently their right to participate in society, notwithstanding their incarceration.

Universal adult suffrage on a common voters roll is one of the foundational values of our entire constitutional order. The achievement of the franchise has historically been important both for the acquisition of the rights of full and effective citizenship by all South Africans regardless of race, and for the accomplishment of an all-embracing nationhood. The universality of the franchise is important not only for nationhood and democracy. The vote of each and every citizen is a badge of dignity and of personhood. Quite literally the judgment says that everybody counts.

Justice Albie Sachs

in the judgment of August v Electoral Commission, 1999

Section 2 - The supremacy of the Constitution

Under Apartheid

Constitutional supremacy replaced the system of parliamentary sovereignty which prevailed under apartheid. Under apartheid, Parliament had the right to make or unmake any law. In practical terms, this meant that the legislature – a body which theoretically represented the will of the people that had the vote under apartheid – could enact whatever legislation it desired. It also meant that Parliament had considerable powers and could enact unjust laws without any guidance from a democratic constitution or a Constitutional Court like we have today.

Further, parliamentary sovereignty meant that no person or body was recognised by the law as having a right to override or set aside the legislation of Parliament. For example, section 34 of the 1983 constitution stated that “no court of law shall be competent to inquire into or to pronounce upon the validity of an Act of Parliament.”

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Section 2 of the Constitution states that “the Constitution is the supreme law of the Republic, and any law or conduct inconsistent with it is invalid, and the obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled”. Constitutional supremacy means that all South Africans are bound by the Constitution as the highest law in the land and that all laws and conduct by public and private actors have to be consistent with the Constitution. As the highest law of a country, the Constitution is at the centre of the political and social life of the country. It defines the relationship between the State and the society, and between the different functions of the State.

In Practice

The supremacy of the Constitution means that even when the majority of the public believes in a particular law, for example the death penalty, their will can be overruled because it has been found to be inconsistent with the Constitution.

In S v Makwanyane, Justice Arthur Chaskalson, then the President of Constitutional Court stated that constitutional supremacy means that the Constitution trumps public opinion. He held that “public opinion may have some relevance to the enquiry, but in itself, it is no substitute for the duty vested in the courts to interpret the Constitution and to uphold its provisions without fear or favour. If public opinion were to be decisive there would be no need for constitutional adjudication”.

The Constitutional Court has struck down a number of laws and conduct inconsistent with the Constitution as the supreme law of the land. For example in Hugh Glenister v President of the Republic of South Africa & Others, the Court found that that Chapter 6A of the South African Police Service Act 68 of 1995, which created the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation, known as the Hawks, and disbanded the Directorate of Special Operations known as the Scorpions, was inconsistent with the Constitution and invalid to the extent that it fails to secure an adequate degree of independence for the DPCI.

Section 3 - Citizenship

Under Apartheid

Under the apartheid racial hierarchy, the white minority had full citizenship while black people who were the majority of the population were not entitled to citizenship. The Citizenship Act of 1970 provided that black people living throughout South Africa were legal citizens in the homeland designated for their particular ethnic group.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

One of the foundational values in the Constitution is that there is a common South African citizenship. The Constitution prohibits the creation of different classes of citizens. By requiring a common South African citizenship, the Constitution prohibits discrimination in respect of citizenship. All citizens are equally entitled to the rights, privileges and benefits of citizenship and are equally subjected to the duties and responsibilities that attach to citizenship. This provision therefore incorporates equality into the notion of citizenship.

In Practice

Kaunda v President of the Republic of South Africa involved an application brought by a number of South African citizens who were detained in Zimbabwe on various charges. It was alleged that they were mercenaries trying to stage a coup in Equatorial Guinea.

The applicants had sought an order directing the South African government to take action at a diplomatic level to ensure their rights under the Constitution were respected. In particular, they sought an order compelling the South African government to ensure that the death penalty would not be imposed on the applicants. The Constitutional Court held that South African citizenship requirements are such that citizens invariably, if not always, will be nationals of South Africa. They are entitled, as such, to request the protection of South Africa in case of need.

Section 4 - National anthem

Under Apartheid

The national anthem under apartheid originated from a poem, Die Stem van Suid-Afrika, written by author CJ Langenhoven in May 1918. The music was composed by the Reverend ML de Villiers in 1921. The South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC), because South Africa at the time was part of the British empire, played both the British anthem God save the King and Die Stem to close their daily broadcasts and the public became familiar with it. Die Stem was first sung publicly at the official hoisting of the national flag in Cape Town on 31 May 1928, but it was not until 2 May 1957 that the government made the announcement that Die Stem had been accepted as the official national anthem of South Africa.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Section 4 of the Constitution states that the national anthem of the Republic is determined by the President by proclamation. A proclamation issued by the (then) President Mandela on 20 April 1994, stated that the Republic of South Africa would have two national anthems. They were Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and Die Stem van Suid-Afrika (The Call of South Africa). However, following a proclamation in the Government Gazette No. 18341 (dated 10 October 1997), a shortened, combined version of Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and Die Stem is now the national anthem of South Africa.

Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika was composed in 1897 by Enoch Sontonga, a Methodist mission school teacher. The words of the first stanza were originally written in isiXhosa as a hymn. Seven additional stanzas (verses) in isiXhosa were later added by the poet, Samuel Mqhayi. A Sesotho version was published by Moses Mphahlele in 1942. Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika was popularised at concerts held in Johannesburg by Nokutela Dube and her husband, Reverend JL Dube’s Ohlange Zulu Choir. It became a popular church hymn that was later adopted as an anthem at political meetings. It was sung as an act of defiance during the apartheid years. The prisoners in the prisons of what is today Constitution Hill, sang the hymn every night at lights out at 8pm.

Section 5 - Flag

Under Apartheid

The old national flag of colonial and apartheid South Africa was introduced from 31 May 1928 and was used throughout the apartheid era. The British flag, which is also known as the Union Jack, was the official flag of South Africa prior to the adoption of the old flag, because the Union of South Africa was considered to be part of the British Empire. The justification for the changing of the flag was that the Union Jack represented only one section of the population, the English. The Minister of Interior, DF Malan, said the flag carried the potential for the resolution of the racial reconciliation between the Afrikaners and the English. For some, the final flag bore as its distinctive features the fusion of the Afrikaner and English traditions. It also became and still is a detested symbol of apartheid for many.

The old national flag was abolished in 1994 by South Africa’s first democratic and non-racial Parliament representing all the people of the country. The last lowering of the orange, white and blue flag was watched in silence by a South African delegation headed by Minister of Justice, Kobie Coetsee of the apartheid government, Namibian President Sam Nujoma and by representatives of African states and the Organisation of African Unity.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

The current South African national flag first flew on 10 May 1994 – the day Nelson Mandela was inaugurated as President, two weeks after the country’s first democratic elections of 27 April 1994.

The Transitional Executive Council (TEC) which governed South Africa after the adoption of the Interim Constitution in 1993 but before the first democratic elections in 1994, could not reach an agreement on all the submissions made by many South Africans on what the South African flag should look like. So the matter of the flag was referred to Frederick Bronwell, the former State Herald of South Africa, who was asked to submit a few designs as he had just designed the Namibian flag.

Bronwell submitted four designs and the TEC agreed on one design which was to become the national flag. That design was presented to Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk, who said that it should be the people that make the decision. Roelf Meyer recalls that a decision was never formally made but it was presented to the people and the current flag literally became the national flag because the people of South Africa accepted it.

The pivotal design of the flag starts at the flag post with a “V” shape which flows into a single horizontal band that leads to the outer edge. This symbolises the convergence of all the diverse South Africans taking a path towards unity.

South Africa’s flag is one of the most colourful, boasting a total of six colours. Some say that the different colours on the flag have a different meaning to different people and therefore there is no singular meaning. However, it has been recorded that the red, white and blue were taken from the flag of the Boer Republics. The remaining three colours – green, black and gold – were taken from the flag of the African National Congress. The green is meant to symbolise the fertility of the land, the black is representative of the people of the nation, while the gold represents the nation’s mineral wealth.

Section 5 of the Constitution provides that “The national flag of the Republic is black, gold, green, white, red and blue, as described and sketched in Schedule 1.”

There are strict protocols regarding the flying of the flag. For instance, at a public event, the flag must be to the right of the speaker.

In Practice

In 2019 the High Court held in Nelson Mandela Foundation Trust v Afriforum NPC and Another, that the gratuitous display of the old flag would now amount to hate speech. This rule extended to public and private areas with the exception where the flag is displayed for “genuine artistic, academic or journalistic expression in the public interest”.

Section 6 - The status of official languages and respect for indigenous languages

Under Apartheid

When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, it consisted of Transvaal, the Orange Free State, Natal and the Cape Province. Dutch and English were the two official languages. However, there were attempts to gradually replace Dutch with Afrikaans. On 8 May 1925, the Official Languages of the Union Act No 8 of 1925 was passed at a joint sitting of the House of Assembly and the Senate. By this Act, Dutch was replaced by Afrikaans. Both Afrikaans and English enjoyed equal status and rights. Afrikaans went on to become the language most closely associated with the formalisation and execution of apartheid.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Section 6 of the Constitution recognises 11 official languages: Sepedi (also known as Sesotho sa Leboa), Sesotho, Setswana, siSwati, Tshivenda, Xitsonga, Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa and isiZulu. South Africa has about 34 historically established languages. Thirty are living languages, and four extinct Khoisan languages.

IsiZulu is South Africa’s biggest language, spoken by almost a quarter (23%) of the population. Our other official languages are isiXhosa (spoken by 16%), Afrikaans (13.5%), English (10%), Sesotho sa Leboa (9%), Setswana and Sesotho (both 8%), Xitsonga (4.5%), siSwati and Tshivenda (both 2.5%), and isiNdebele (2%).

The nine African languages can be broadly divided in two:

- Nguni-Tsonga languages: isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, siSwati, Xitsonga

- Sotho-Makua-Venda languages: Sesotho, Sesotho sa Leboa, Setswana, Tshivenda

There are many more languages in South Africa that may not be official but exist within our diverse communities. Section 6(5) of the Constitution states that a Pan South African Language Board (PANSLAB) established by national legislation must promote and create conditions for the development and use of –

- all official languages

- the Khoi

- Nama and San languages

- sign language

PANSLAB also must promote and ensure respect for all languages commonly used by communities in South Africa, including German, Greek, Gujarati, Hindi, Portuguese, Tamil, Telegu and Urdu. In addition PANSLAB must promote and ensure respect for Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit and other languages used for religious purposes in South Africa.

Implied Foundational Values and Principles

There are values that are central to our Constitution that do not appear explicitly in the text like the foundational values set out in Chapter 1 of the Constitution, but which are implied in the architecture of the Constitution and which are just as important as the explicit values.

Ubuntu

South Africa has a history of deep divisions characterised by strife and conflict. However, one shared value and ideal that runs like a golden thread across its indigenous cultures, is the value of ubuntu – a notion now in post-apartheid South Africa that relates closely to the constitutional values of dignity, freedom and equality. Ubuntu means that motho ke motho ba batho ba bangwe/umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu which, literally translated, means a person is a person because of others.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

The Interim Constitution explicitly refers to ubuntu. Its text recognised that despite the injustices of the past, there is a need for understanding, not vengeance and a need for reparation, not retaliation. In addition, the Interim Constitution recognised the need for ubuntu and not victimisation.

South Africa’s 1996 Constitution makes no express mention of ubuntu. It does however recognise customary law. The Constitution requires the courts to apply customary law “when that law is applicable, subject to the Constitution and any legislation that specifically deals with customary law”. Ubuntu is inherent to customary law.

What Does Ubuntu Mean?

Justice Mokgoro writes that the concept of ubuntu, like many African concepts, is not easily definable. To define an African notion in a foreign language can be particularly elusive. Ubuntu has been described as a philosophy of life, which in its most fundamental sense represents personhood, humanity, humaneness and morality; a metaphor that describes group solidarity where such group solidarity is central to the survival of communities with a scarcity of resources. The fundamental belief that a person can only be a person through others means that an individual’s whole existence is relative to that of the group: this is manifested in anti-individualistic conduct towards the survival of the group if the individual is to survive. It is a basically humanistic orientation towards fellow beings.

A culture which places some emphasis on communality and on the interdependence of the members of a community. It recognises a person’s status as a human being, entitled to unconditional respect, dignity, value and acceptance from the members of the community such a person happens to be part of. It also entails the converse, however. The person has a corresponding duty to give the same respect, dignity, value and acceptance to each member of that community. More importantly, it regulates the exercise of rights by the emphasis it lays on sharing and co-responsibility and the mutual enjoyment of rights by all.

Justice Pius Langa

in the Judgment of S v Makwanyane, 1995

In Practice

In S v Makwanyane, Justice Mokgoro made the connection between ubuntu and dignity. She has argued that in interpreting the Bill of Rights in an all-inclusive value system in South Africa, ubuntu can form a basis upon which to develop a South African human rights law. Since S v Makwanyane, ubuntu has become an integral part of the constitutional values and principles that inform interpretation of the Bill of Rights and other areas of law. In particular, a restorative justice theme has become evident in the cases that encompass customary law, eviction, defamation, and criminal law matters.

Judicial Review

Under Apartheid

South African history demonstrates the vulnerability of the judiciary to manipulation by the apartheid government even while the pretence of independence was maintained. The apartheid government claimed consistently that the judiciary was independent. While formal structural guarantees of independence existed, and whilst at times the courts issued judgments contrary to the wishes of the apartheid government, a closer examination of the judiciary’s position reveals that the judicial branch was not truly independent. It did not effectively curb abuses of power by the other branches of government.

Under apartheid the approach to law that dominated the South African courts was that the law was to be interpreted within the framework of the words used by Parliament. The courts were not empowered to make any alterations or additions to the text of the law, as this function was solely the responsibility of Parliament. Under apartheid, courts were limited to enforcing the will of Parliament without any scrutiny as to how fair or just those laws were.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

Under apartheid, Parliament could overrule the courts but under a constitutional democracy, courts are independent and can overrule Parliament if its laws or conduct are inconsistent with the Constitution. This power that the judiciary has to scrutinise the conduct of elected branches of government such as the executive and Parliament is what is referred to as ‘judicial review’.

Although the phrase ‘judicial review’ does not appear in the text of the Constitution, the Constitution does, however, explicitly endow the courts with the authority to review the conduct of the other elected branches of government. Judicial review ensures that the roles and powers of state institutions are exercised in accordance with the Constitution. All constitutional democracies around the world give effect to judicial review. The independence of the courts is guaranteed by section 165(2) of the Constitution which provides that “the courts are independent and subject only to the Constitution and the law, which they must apply impartially and without fear, favour or prejudice.” This provision safeguards the judiciary from political interference and manipulation, thereby ensuring that the judiciary can objectively judge the conduct of the other branches of government.

Section 167 (4) provides that only the Constitutional Court can, amongst other powers, decide disputes between organs of state in the national or provincial sphere concerning the constitutional status, powers or functions of any of those organs of state; decide on the constitutionality of any parliamentary or provincial bill, and decide that Parliament or the President has failed to fulfil a constitutional obligation. The power of judicial review has often led to a clash between the executive and the judiciary. Some may argue that the powers of judicial review violate the doctrine of separation of powers.

As we have seen, separation of powers and provisions intended to be checks and balances do not mean that the three branches of government leave each other untouched. The judiciary is tasked with overseeing the compliance of the law by all branches of the state, its organs and all inhabitants of the Republic. The judiciary does not descend into the arena on a whim, but on a clear and dutiful mandate by the Constitution. When it does, the judiciary must not unduly trespass the terrain of other arms of the state. However, when the Constitution requires that the judiciary decide a particular controversy, that can never amount to overreaching. If it is trespass at all, it is one that the Constitution itself allows.

Then Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke

in a speech delivered at the University of the Western Cape, 2015

In Practice

The Constitutional Court has exercised judicial review powers in a number of judgments. For example, in all its socio-economic rights cases, the Court is essentially reviewing the government’s conduct in realising socio-economic rights.

In the Government of the Republic of South Africa versus Grootboom, the Constitutional Court reviewed the government’s housing policy. The Court adopted a cautious approach in interpreting the right to housing. In this case it was made clear by the Constitutional Court that it did not intend to take over the functions of the other branches of government, and that it did not have the expertise to draft the State budget nor to develop and implement policies. However, the Court did find that the government’s housing policy fell short of the demands of the right to access to housing set out in section 26 and that its policy on emergency housing was inadequate.

Separation of Powers

Under Apartheid

From its founding in 1910, the Union of South Africa was based on the Westminster system of government. This meant that the executive was responsible to, and formed part of, the legislature.

Even though the judiciary held a relatively independent position within this system, judges were appointed by the executive, meaning the executive could interfere with the judiciary. Also, the powers of the courts to check the conduct of the legislature and the executive were severely curtailed by what was referred to as ‘ouster clauses’ which were provisions in legislation that took away or purported to take away the jurisdiction (powers) of the courts.

This close relationship between the executive and Parliament, and the limitation on the powers of the court, meant that there was no real separation between the functions of these three branches of government. Neither branch of government was independent enough to check the conduct of the other branch of government.

The 1983 constitution brought about some changes to this system. For example, the President ceased to be a member of Parliament. However, the interwovenness of Parliament and the executive continued until the advent of the Interim Constitution in 1993.

In the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa of 1996

The doctrine of separation of powers does not appear by name in the Constitution. However, there is no doubt that it is accepted as a dominant organising principle of state power. Separation of powers is clearly implied in the manner in which the Constitution divides power and functions amongst the different branches of government.

The doctrine of separation of powers means that specific functions, duties and responsibilities are allocated to distinctive arms of government with a defined means of competence. In one respect it is a separation of three main spheres of government, namely, legislative, executive and judiciary. Within the constitutional framework the meaning of the terms legislative, executive and judicial authority is of importance:

- Legislative authority – The power to make, amend and repeal laws.

- Executive authority – The power to execute and enforce laws.

- Judicial authority – The power, if there is a dispute, to determine what the law is and how it should be applied in the disputes.

It is often said that separation of powers is a system of checks and balances. The general purpose of checks and balances is to make branches of government accountable to each other. Checks ensure that the different branches of government control one another internally, while balances serve as counterweights to the power possessed by the other branches.

Unlike under apartheid, judges are no longer appointed by the executive but rather are appointed by an independent body called the Judicial Services Commission. Also, the judiciary is given clear powers by the Constitution to check the conduct of Parliament and the executive.

The doctrine of separation of powers means ordinarily that if one of the three spheres of government is responsible for the enactment of laws, that body shall not also be charged with their execution or with judicial decision about them. The same will be said of the executive authority. It is not supposed to enact law or perform the functions of the judiciary and the judicial authority should not enact or execute laws.

The separation of powers between the three branches of government is not always simple as functions may overlap in some respects. For example, although law making powers are generally vested with Parliament, the courts through the judgments do make law and the executive has limited law making powers in that it can make subordinate (secondary) laws.

Although it is fundamental to democratic legal systems around the world, the doctrine of separation of powers is not rigidly defined. As the Constitutional Court pointed out in the First Certification judgment, “there is no universal model of separation of power … and in democratic systems of government … there is no separation that is absolute”.

In Practice

The question of whether or not the doctrine of separation of powers forms part of the 1996 Constitution has been considered and explained in several Constitutional Court cases. In Glenister v President of the Republic of South Africa, Chief Justice Langa confirmed that “the doctrine of separation of powers is part of our constitutional design”.

In the South African Association of Personal Injury Lawyers v Heath and Others case, Chief Justice Chaskalson stated that our Constitution is structured in a way that makes provision for a separation of powers. There can be no doubt that our Constitution provides for such a separation.

In Bernstein v Bester, the Court held that legislation that sought to bring the judiciary under the control of Parliament or the executive could be struck down under the doctrine of separation of powers, even if there was no express conflict between such legislation and the Constitution.

In De Lange v Smuts, the Court observed that: “[There is] no doubt that over time our courts will develop a distinctively South African model of separation of powers, one that fits the particular system of government provided for in the Constitution and that reflects a delicate balance informed both by South Africa’s history and its new dispensation, between the need, on the one hand, to control government by separating powers and enforcing checks and balances, and on the other to avoid diffusing power so completely that government is unable to take timely measures in the public interest.”