Founding the

new

court

The Interim Constitution established a Constitutional Court consisting of a President and ten justices. It would be a brand new court using completely new values with unprecedented responsibilities and powers. Soon after his inauguration on 10 May 1994, President Nelson Mandela appointed Arthur Chaskalson as President of the Court and then four judges taken from the ranks of the higher judiciary. The six remaining justices were selected from a list of ten lawyers prepared by the Judicial Services Commission (JSC) after it had publicly interviewed 21 candidates.

The result was that the first bench was made up of four independent-minded judges from the apartheid era, plus two recently-appointed judges, two advocates and three law professors who had distinguished themselves as lawyers fighting for human rights and social justice. Together, the justices set out to tackle the many complex and interesting decisions required to bring to life a new court. They laid the foundation for a Court that became known for its collegial and non-hierarchical style of work, for robust internal debates that produced powerful and well-reasoned judgments and for its general accessibility to the people of South Africa.

Navigate this section

The Appointment of Judges

In June 1994, President Mandela, in consultation with the cabinet and Chief Justice of the Appellate Division, Michael Corbett, appointed Arthur Chaskalson to be the first President of the Constitutional Court.

I got a message that the President wanted to see me … When I got [to the Union Buildings], he immediately wanted to know whether I would do him the honour of becoming the President of the Constitutional Court, which was his way of putting things.

Arthur Chaskalson

reflecting on the moment of being offered the position of head of the Court

Chaskalson was a towering figure in South Africa’s legal landscape at the time. He had been a member of the defence team in the Rivonia Trial of 1963 and had subsequently acted as the defence counsel for anti-apartheid activists in several high profile trials. In 1978, he became the founder and director of the Legal Resources Centre which fought for justice and human rights and provided legal aid to poor and marginalised communities. During the negotiations, he became a member of the ANC Constitutional Committee and was characterised as one of the most influential participants – particularly in the process of writing the Interim Constitution. In the words of President Mandela, he was a man of ‘measureless integrity’.

Front row [L-R]: Kobie Coetzee (Minister of Justice), Frene Ginwala (Speaker of the National Assembly), President Nelson Mandela, Deputy President Thabo Mbeki, and Michael Corbett (Chief Justice at the time). Back row [L-R]: Yvonne Mokgoro, Kate O’Regan, Richard Goldstone, Ismail Mahomed, Arthur Chaskalson (President of the Constitutional Court), John Didcott, Albie Sachs, Laurie Ackerman, Pius Langa (Deputy President of the Constitutional Court), Sydney Kentridge, Tholie Madala. Private collection of Albie Sachs

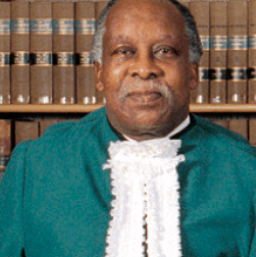

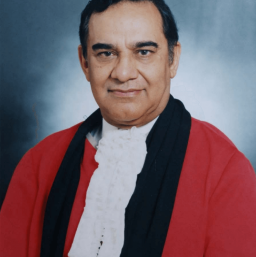

Again, in consultation with Michael Corbett and Arthur Chaskalson, President Mandela then appointed four judges from the ranks of the Appellate Division, the highest court under apartheid. An important consideration for their appointment was how they had conducted themselves within the apartheid legal system. Justices Laurie Ackerman, Richard Goldstone, Tholie Madala and Ismail Mahomed were appointed.

They were perceived to be very progressive judges, whose records indicated that they subscribed to the culture and principles of the new constitutional order.

Justice Pius Langa

then Deputy President of the Constitutional Court

The remaining six judges went through gruelling interviews before being appointed in October 1994. The Judicial Services Commission (JSC), headed by Chief Justice Corbett, and consisting largely of judges, legal professionals and members of Parliament, publicly and vigorously interviewed 25 out of an original list of 100 candidates. One of the major guiding principles was the ‘need for the judiciary to reflect broadly the racial and gender composition of South Africa’.

The process of appointing the judges was entirely transparent and the JSC interviews were conducted in public with the media present. The JSC received comments and views from the public about the suitability of the candidates. This was a decisive break from the past where judges were appointed in secret by the State President or, at a later stage, on the recommendation of the Chief Justice. The aim of the process is to preserve the integrity of the Bench by ensuring public participation and high levels of transparency.

Following the interviews, the JSC submitted a list of ten candidates to President Mandela, who, again after consultation with the Cabinet and now with Arthur Chaskalson, the newly elected President of the Constitutional Court, appointed the final six judges. They were Yvonne Mokgoro, Pius Langa, Kate O’Regan, Albie Sachs, Johann Kriegler and John Didcott. With the exception of John Didcott, not one of the other five appointees had ever been a judge before.

The eleven judges were to serve for a single, non-renewable term of initially seven years. Later, the Constitution provided that Constitutional Court judges would be appointed for a non-renewable term of 12 years but must retire at the age of 70. In 2001 the positions of President of the Constitutional Court and Chief Justice were merged, and President Chaskalson became Chief Justice Chaskalson.

Our backgrounds before being appointed to the Court could not have been more varied. We were advocates, judges from other courts and law professors … one had got his law degree while a prisoner on Robben Island. One had been a court interpreter, another a nurse … Yet motley as our lives and professional experiences had been, we quickly became a warm, collegial and united court … We all felt it a great privilege to be on the Court. There can be no greater challenge and no greater pleasure for a judge than to feel part of a generation that lays the foundations of a creative, principled and operational jurisprudence of constitutional democracy that will endure.

Justice Arthur Chaskalson

in the special anniversary publication, The Constitutional Court of South Africa: The First Ten Years, 2005

The face of the judiciary had substantially changed. Yet the challenge to meet the Constitution’s demand for a judiciary representing both the racial and gender composition of South Africa had not been entirely fulfilled. However, today’s bench is much closer to the diverse representation envisioned by the Constitution.

But when you look at the gender representivity in the Court – women are not as well represented as one would have wished. But there has been at least some development, some changes.

Justice Bess Nkabinde

The Court is inaugurated

On 14 February 1995, in a makeshift courtroom in a Braamfontein office park, President Nelson Mandela inaugurated the Constitutional Court and poignantly opened the ceremony saying:

The last time I appeared in court was to hear whether or not I was going to be sentenced to death. Fortunately for myself and my colleagues we were not. Today I rise not as an accused but, on behalf of the people of South Africa, to inaugurate a court South Africa has never had, a court on which hinges the future of our democracy.

FORMER President Nelson Mandela

speech at inauguration of the Court, 1995

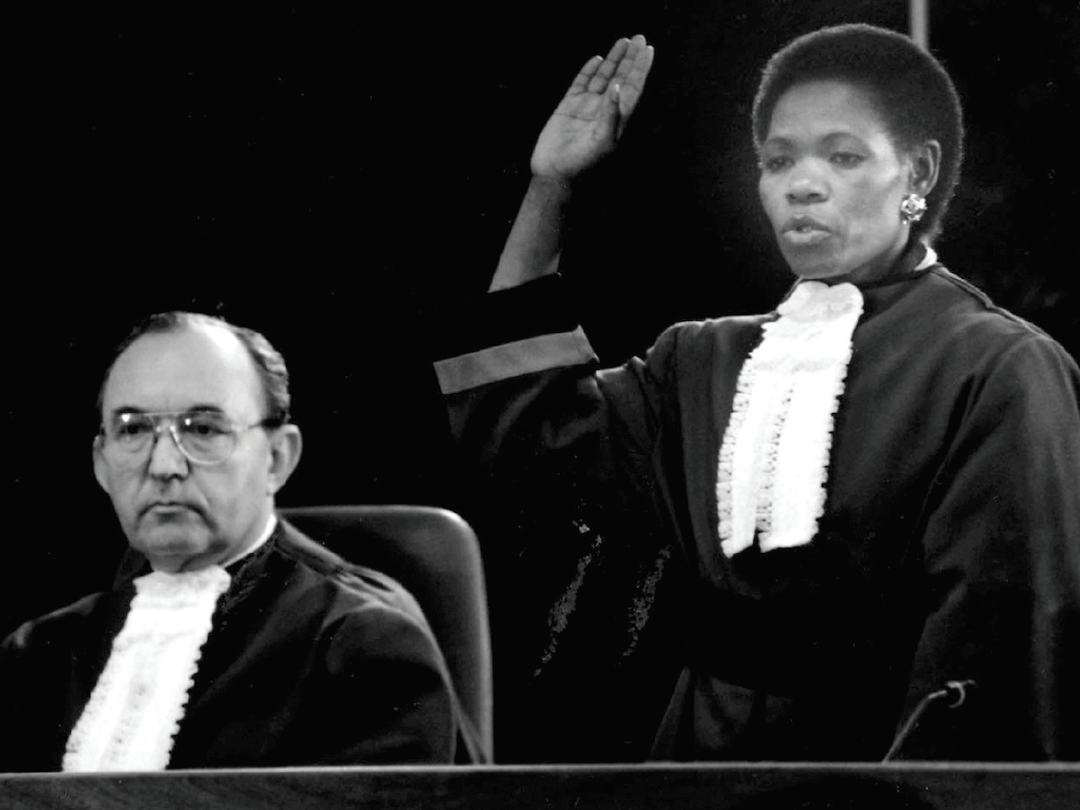

The judges took their oath of office in front of President Mandela and the Minister of Justice, Dullah Omar.

I, A.B., swear/solemnly affirm that, as a Judge of the Constitutional Court, I will be faithful to the Republic of South Africa, will uphold and protect the Constitution and the human rights entrenched in it, and will administer justice to all persons alike without fear, favour or prejudice, in accordance with the Constitution and the law. (In the case of an oath: So, help me God.)

With six judges speaking in English, two in Afrikaans, one in isiZulu, one in seSotho and one in isiXhosa, a new respect for language diversity

was already being instituted.

To Judge Arthur Chaskalson and other members of the Constitutional Court let me say the following: yours is the most noble task that could fall to any legal person. In the last resort, the guarantee of the fundamental rights and freedoms for which we have fought so hard lies in your hands. We look to you to honour the Constitution and the people it represents. We expect from you, no, demand of you, the greatest use of your wisdom, honesty and good sense – no shortcuts, no easy solutions. Your work is not only lofty, it is also lonely.

Former President Nelson Mandela

At the inauguration of the Court, 1995

And indeed, the newly appointed Justices had been given a lofty and noble task. As the ultimate guardians of South Africa’s hard-won constitutional democracy, they were also now responsible for certifying the Constitution of 1996.

It was both fascinating and exhilarating to be part of this. The Court had to establish its jurisprudence, almost from scratch. Again, this was a momentous responsibility. But perhaps the most important achievement was the acceptance of the Court’s work by the South African people. This established the position of the judiciary, and its independence, as being a key part of the South African firmament.

Justice Pius Langa

then Deputy President of the Constitutional Court

Within 24 hours of the inauguration, the Court would be hearing its first and one of its most challenging cases – the question of the

constitutionality of the death penalty.

It was a new Court. Some of us had high expectations that it will bring about changes, that it would take the lead in construing the Constitution and lead us in understanding this new system … So we expected the Constitutional Court to take the lead in shaping the new legal system. Which it did.

Justice Chris Jafta

Inventing a new institution

In the first informal meetings of the eleven judges, they understood that they had been given a blank cheque. The judges had the task of inventing a brand new institution. They had to decide how the Court would function and all other elementary ‘household’ arrangements.

Here we had this Court with new ideas, a new face of the Court, and people who were driven by a desire for social justice. These judges started from nothing. I mean, nothing. No rules, no chamber, absolutely nothing. You looked at the Court with admiration, and you looked at the judges with admiration. These people started this from nothing, and there they are transforming our society in this way.

Justice Bess Nkabinde

Here are just some of the decisions that had to be taken and how they were resolved.

What is the Court’s new symbol?

How would the Court’s logo convey its place in Africa, the Constitution’s historical roots in the struggle for human rights and be infused with the spirit of a new democracy? How would it confirm the Court’s ethos and culture as a source of protection for all especially as the justice system under apartheid had been so tainted?

The Court’s logo is based on the notion of ‘justice under a tree’. This is a direct reference to lekgotlas, the traditional African way of consultation and resolution of differences. Village elders preside to rule on community affairs, often under a tree. The logo signifies a new kind of justice in South Africa – one that would protect the rights of people.

Should there be any hierarchy amongst the judges?

“The first meeting was quite amusing with Justice Laurie Ackermann suggesting that the order of seniority should be alphabetical and Justice John Didcott, who was the oldest member of the Court, suggesting that it should be determined by age.”

-Justice Richard Goldstone

The judges decided on an anti-hierarchical court with no rule of seniority amongst them.

How would the judges be addressed?

Would they keep the old tradition of being addressed as ‘My Lord’ or ‘My Lady’?

The judges were adamant that they would not be addressed by these titles under the old tradition. As part of creating a court that was a sharp break from past traditions, meant that they should be addressed simply as ‘justices’.

What would the judges wear?

“Should we robe or not robe? After all we were a new court with new ideas of justice. Some had the idea that maybe we shouldn’t robe and then the counter idea was no, we need to robe. We need to look like a Court because if we don’t robe, it would not be convincing. What won at the end of the day was the fact that we should robe and then the question became, what colour? Should it be different, should it be the same?”

-Justice Yvonne Mokgoro

As a new post-apartheid institution, the judges wanted to make a statement through their robes which would set them apart. They decided on a specially designed green robe with red and black trim.

What kind of institutional culture should be created?

How would the Court animate the ideals of the Constitution?

The judges set out to create a collegial court where they could openly share their views with one another. The Court’s working culture, in order to live the ideals of the Constitution, had to be consultative and collaborative. This would ensure a diversity of perspectives that would enrich the Court’s jurisprudence.

How should the judgments be written?

How could they be made accessible for non-lawyers?

“The quality of the judgments has a lot to do with the collegial approach to them.”

-Justice Johann Kriegler

How should the Court be staffed?

What considerations should be taken into account?

Initially, the Court had no staff but soon the judges were able to appoint law clerks who would support the judges with research and writing judgments.