Constructing

A New Home

On 14 February 1995, just less than a year after South Africa’s first democratic elections, President Nelson Mandela inaugurated South Africa’s first Constitutional Court. It was initially located in makeshift accommodation in an office block in Braamfontein, Johannesburg. The inauspicious building was offset by the significance of this new Court. Nonetheless, it was clear from the very start that a new building for the Constitutional Court would have to be built. This was to be South Africa’s first national post-apartheid government building.

This is a young country. People feel deeply and passions swirl. The Constitutional Court, possibly more than any other institution, stands for, defends and symbolises the integrity of our nation and the fundamental rights of all our citizens. We want a place that will reflect the importance with which people view this Court, the role it plays in their lives and its function of ensuring that the Constitution is sovereign.

Justice Pius Langa

then Deputy President of the Constitutional Court

The dramatic change in South Africa was not from white to black, but from the rule of men to the rule of law. It was a natural consequence that it was the Constitution that was going to be the prevailing power in the new South Africa. It followed that the body that was the protector of the Constitution – the Constitutional Court ‑ should be recognised by a building of commensurate importance. It was going to be the first major building of the new South Africa and the first major public building.

Justice Johann Kriegler

Navigate this section

Some Of Our Storytellers

FLO BIRD

JUSTICE PIUS LANGA

JUSTICE JOHANN KRIEGLER

JUSTICE ALBIE SACHS

JUSTICE KATE O’REGAN

JUSTICE SISI KHAMPEPE

JUSTICE YVONNE MOKGORO

JEFF RADEBE

HERBERT PRINS

Choosing a Site

The first task of the Department of Public Works (DPW) – which was the government ministry responsible for building the new Constitutional Court – was to work with the City Council to find a suitable site. The Court was a prestigious tenant and many interested landlords vied to attract the judges to their premises.

We were wooed by many people who tried to persuade us to build the Constitutional Court on their site. We visited Crown Mines, the old synagogue in Wolmarans street, and down near Anglo American where De Beers is, and the Johannesburg Technikon … I was looking at all of these sites with only half an eye because I knew where we were going.

Justice Johann Kriegler

The Wolmarans street shul is a fascinating building, but it didn’t breathe. The independence of the Court required that it had its own space, that it should not be too crowded by the city. We were also referred to the old post office. It’s a marvellous old building, but again it’s crowded in by the city.

Justice Albie Sachs

We were shown the Pieter Roos Park where the Court would be in a slightly more contemplative setting than at the inner-city sites. But there are so few green spaces in Johannesburg that I was opposed to the idea of diminishing public open spaces.

Justice Kate O’Regan

Visiting the Old Fort

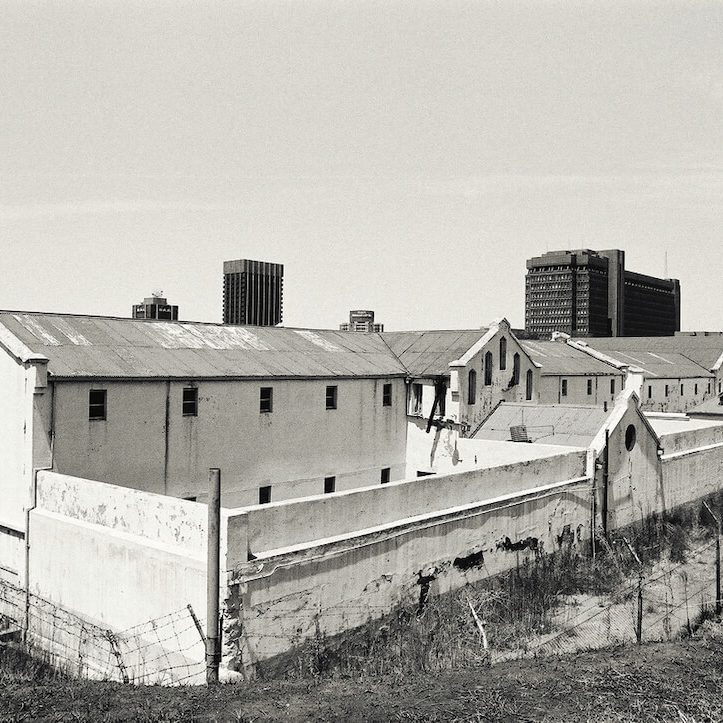

One of the sites suggested by the Johannesburg City Council was the Old Fort prison, parts of which were occupied at the time by the Rand Light Infantry and the Johannesburg Security Department. The judges visited the site as a large group.

the Fort.

Justice Yvonne Mokgoro

I had known about this site for donkeys’ years. When I was still practicing at the bar, I used to come and see clients here. Also, I’m a Joburg freak, and I went to the Fort after the prisons department had abandoned it on more than one occasion. I felt like a little boy – there was something adventurous about coming to this abandoned place.

Justice Johann Kriegler

I’d never been there. I hadn’t interviewed clients there. I hadn’t been locked up there but in Cape Town. It had a totally ruined, derelict character. But it was the site’s potential for renovation and resurrection that was so captivating. My heart just flipped, because the chance of turning things around, which we’ve done with our country, was so intense and powerful.

Justice Albie Sachs

I recall wading our way through long grass and black jacks and rubble all over the place, and having a look and realising that indeed it would be a remarkable site for the Court, even though it did look a bit like a rubbish dump at the time.

Justice Kate O’Regan

I remember my mother used to visit a relative of mine who was also incarcerated under the terrorism act and would say every time, ‘I’m going to Number 4’ … a terrible place … With time I saw that there was a need for the Court, given its stature and its mandate, to be located in a place such as this one.

Justice Sisi Khampepe

The hidden attractions

Through the weeds, the rubble and the ruins, the judges could see the potential of the prison site. Its location in the inner city, the views it commanded over Johannesburg and most importantly, the history of the prison were all compelling reasons for the judges to locate the Court at Number Four.

I was very excited about converting this place, not just physically, but emotionally too into a place that protected human rights. The site would urge us not to forget what happened in the past. The bricks would be there as reminders that this is a route that we never, never want to take again.

Justice Yvonne Mokgoro

We felt excited by the symbolism of the old prison, whose function had once been so oppressive, becoming, under the Constitution, a place representing freedom and human rights.

Justice Pius Langa

then Deputy Chief President of the Constitutional Court

The location cheek by jowl with Hillbrow was a draw card rather than a detractor. We were particularly concerned about not having a remote, alien place. To place the Constitutional Court where it was accessible was a non-negotiable.

Justice Johann Kriegler

The other wonderful thing was that it is both looked upon and commands a view, which seemed appropriate for a court like this.

Justice Kate O’Regan

Before the Court moved to Constitution Hill, Justice Sachs used to take us to the site. He told us it was a prison before and when he explained to us the reason why they chose this site, I thought it was reasonable for me because it’s in the centre of Joburg, its where people who just have no money or who need to come to Court, with legs or with a train, they can manage to come.

Godfrey Disemelo

head of security at the Constitutional Court

Demolishing the Awaiting Trial Block

Together with two advisory architects, Vivien and Derek Japha, the judges identified the position for the Court at the highest point on the northern slope of the site. But they were faced with a dilemma. The Awaiting Trial Block (ATB) part of the prison complex was in the way. The prison was symbolic of the very nature of the jail – black men and women repeatedly being arrested and criminalised because of the colour of their skin. The prison had, over the years, also housed waves of political prisoners, including the treason trialists in 1956 and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) anti-pass protesters led by Robert Sobukwe. Passions and principles came to the surface in a debate about whether or not the ATB could be demolished.

One day, Derek Japha and I walked over to the site. He said he thought it was a wonderful site for a new building. It’s got space. It’s got slope. It’s connected with the urban fabric, but not dominated by it. He was very inspired. But he said if we kept the Awaiting Trial Block, the Court would be overshadowed by it. It wouldn’t have any space. The prison would have to go.

Justice Albie Sachs

The National Monuments Council was immediately up in arms. They thought we were going to destroy a national heritage site. I had a fairly pungent response for them: ‘You heritage people have got a temerity to talk about us wanting to destroy it. You’re allowing it to go to wreck and ruin. When last did any of you go and have a look at it? Ceilings are being taken out and hobos are occupying it.

Justice Johann Kriegler

The Monuments Council and its successors have always had a terrible problem – the legislation provides for all kinds of strong preservation measures, but neither now, nor in the past, have there been the necessary funds from the government to make it possible for the Council to carry out their preservation functions properly.

Herbert Prins

then heritage consultant

Differing views

A decision had to be made. The National Monuments Council (NMC), the national heritage conservation authority of South Africa, wanted the Court on site but they strongly opposed the demolition of the Awaiting Trial Block (ATB). The judges stood firm.

When the NMC said to the judges ‘We love the idea that you build your Court here, but we think you should keep the Awaiting Trial Block,’ this fell to some extent on deaf ears. It came to a point where there was an impasse between the judges and the Monuments Council. The judges said ‘Look, this is where the Court should go. And if we can’t build our Court there, then we will have to look somewhere else for a site’.

Herbert Prins

then heritage consultant

There was a hell of a fight. I was absolutely horrified, because we felt that the Awaiting Trial Block was tremendously important. And of course, the City Council and the Central Johannesburg Partnership were leaning very heavily on the Monuments Council to give the Court permission to knock it down.

Flo Bird

member of the National Monuments Council

Quite frankly, I am not a great fan of prisons and I don’t feel this huge regret when prisons are razed to the ground. What was it going to be used for, a rather ugly, 1940s building, in which people had suffered enormously, very often unjustly? That something can rise, phoenix-like from the ashes, which is the antidote to it, seems to me to be a powerful message of possibility for transformation in South Africa. I suppose it’s very difficult to get everybody to agree.

Justice Kate O’Regan

A decision was eventually made in early 1997. The National Monuments Council (NMC) gave way to the judges’ request that the Awaiting Trial Block (ATB) be demolished to make way for the new Court. As part of the agreement, the NMC insisted that the building be commemorated as part of the new developments.

There was really no alternative but to give permission to demolish the Awaiting Trial Block. The Court presented us with an incredible opportunity to take care of the site. This decision has been very seriously criticised by many people, particularly ex-prisoners, who feel that that particular building had a very important place in the whole complex.

Herbert Prins

then heritage consultant

I am happy to have been the mayor at the time the Council agreed. I pushed to put the Constitutional Court there, as this is a victory for the people who once were in the prison. It is a way of honouring their part in the struggle for liberation.

Isaac Mogase

then Mayor of Johannesburg and former prisoner at Number 4

Consensus was reached with the heritage representatives that we could use the site but would make as little of an inroad as possible into the other prison buildings. The thought that The Old Fort was going to be preserved and that Number Four was going to be preserved was a wonderful relief.

Justice Johann Kriegler

The Old Fort was the Robben Island of Johannesburg. A new Constitutional Court rising there would dramatise the transformation of South Africa from a racist, authoritarian society to a constitutional democracy … This wasn’t just a neutral space – this was a space of intense drama, of human emotion, of repression, of resistance. And here was the chance to convert negativity into positivity.

Justice Albie Sachs

A new design approach

Public buildings in South Africa are usually designed in-house by the Department of Public Works (DPW) or by DPW appointed architects. The judges felt, however, that the new Court should reflect the excitement and optimism about a new accessible system of justice that the new Constitution brought with it. They decided that a competition would be the best way to break with the intimidating and derivative public architecture of the past.

This serves as an apex Court in all constitutional matters and matters of general public importance so it must be seen to be different because the work that it does is more than demanding.

Justice Sisi Khampepe

When the government hands out work to its favourites, the favourites produce what they think the government wants. For the sake of good architecture, you need competitions. That’s how you get fresh ideas and innovation.

Justice Albie Sachs

merging architects.

Ian Phillips

then special advisor to Minister of Public Works

This is the first architectural competition which has been approved by the government as an alternate way for the state to engage in the design of important sites that reflect our legacy.

Jeff Radebe

then Minister of Public Works

Trusting our own imaginations

A diverse set of skills and political acumen was needed for the job of drawing up the competition brief. A number of interested parties got involved, including the Department of Justice, which was putting up the money; the Department of Public Works, which was responsible for public buildings; the Johannesburg Metropolitan Council, which owned the land and were interested in the development of the Court; the National Monuments Council (NMC), which was concerned about what was going to happen to heritage buildings; and, of course, the judges themselves.

Why were the judges themselves so involved in the building project? I never thought of it as anything but a public trust. We are the Constitutional Court; we are establishing a monument; it has got to be worthy of that trust that has been given to us. All human beings – let me say all males – are ego-driven. The thought that we could contribute to something concrete, something for the ages, was very exciting. We were destiny aware. We were making jurisprudence and a building to go with it.

Justice Johann Kriegler

their own.

Justice Laurie Ackermann

The design brief

The Department of Public Works agreed to waive its space specifications for the new building. Architects, government officials, heritage experts and the judges debated and decided on issues ranging from the detailed specifications for the Court chamber to personal ablution facilities.

We needed to describe an African court in all its character – physically and psychologically. We wanted to capture the spirit of an African building; open, welcoming, warm and accessible. In Tswana, we have an expression ‘Kago ee bontshang botho’ meaning a building with humanity, a place where you want to be because you feel that you are valued as a human being. Your dignity is recognised and treasured.

Justice Yvonne Mokgoro

Of all the drafting I’ve done in my life, including helping draft sections of the Constitution, this must have been amongst the most delicate and interesting. We spent months on the brief, both on getting the text and the specifications right. But the key thing wasn’t the accommodation, that was straightforward. The difficult thing was describing the character of the building.

Justice Albie Sachs

We made some important interventions. The Department of Public Works states that judges are entitled to private bathrooms. We traded in that privilege for extra space in our chambers. Having communal toilets is more sensible for plumbing purposes than having private ones.

Justice Johann Kriegler

- The building must be rooted in the South African landscape, both physically and culturally.

- It should not overemphasise the symbols or vernacular expressions of any section of the population, nor be a pastiche of them all.

- It should weather gracefully and be made of material which is enduring.

- It must be restrained, simple and elegant rather than opulent, garish or ornate.

- It should have a distinctive presence, as befits its unique role and should convey an atmosphere of balance, rationality, security, tranquillity and humanity.

- It should be dignified and serious, but it should have a welcoming, open and attractive character and make everyone feel free to enter and safe and protected once inside.

The competition

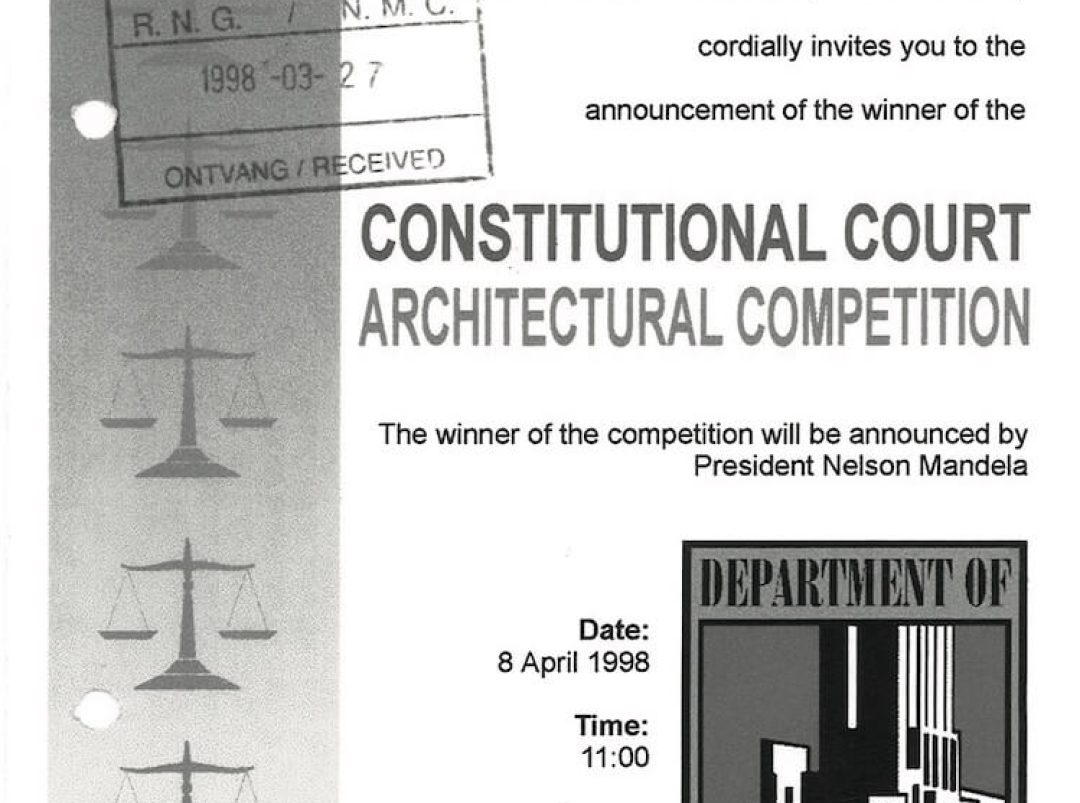

The nature of the competition itself also came under scrutiny. After much debate, the judges and the Department of Public Works decided to go for an international, two-stage competition. The first stage required submissions on the key concepts for the Constitutional Court and for the development of the site as a whole. The second stage would involve five finalists who would submit detailed design proposals for the Court and the environs. Non-architects were encouraged to participate because there were very few trained black architects in South Africa at that time. All entrants would be anonymous.

Spurred on by the democratic experience of the Constitutional Assembly, which brought all of our people into the task of writing our new democratic Constitution, we insisted that we must ensure that as many people who wished to make a contribution to the design of the Constitutional Court should do so, regardless of whether they are qualified architects or not.

Jeff Radebe

then Minister of Public Works

The competition was structured so that anyone could put forward their vision for the site.

Vivien Japha

then vice-president of the South African Institute of Architects

I motivated very strongly for a national competition. I said, ‘It’s our Constitution; it’s our history. We’ve got architects. We can do it.’ But Laurie Ackermann said, ‘Go for an international competition. If South African architects are the best, then they’ll win.’

Justice Albie Sachs

The jury

Eight people representing the various interest groups were selected for the jury. Albie Sachs represented the Court, and Herbert Prins, the National Monuments Council. Isaac Mogase, an ex-prisoner at Number 4 and the mayor of Johannesburg at the time, represented the local council, and Gerard Damstra, also an architect, the Department of Public Works. Willie Meyer represented the South African architectural profession. Three major international architecture figures made up the rest of the jury: Charles Correa of India, Geoffrey Bawa of Sri Lanka and Peter Davey, UK-based editor of the Architectural Review. Thenjiwe Mtintso, also an ex-prisoner at the Women’s Jail and chair of the Commission on Gender Equality, was approached when it became apparent that there were no women on the jury.

I brought in my own particular expertise of being a freedom fighter, an African woman, a former detainee of the notorious women’s prison. I asked myself what the building should say to women. I took what I knew from my late mother, a poor black woman who grew up in the rural areas and migrated to the informal settlements of Joburg. She would say that these places scare the hell out of you. ‘They are ugly, heavy and austere.’ She knew, because she was regularly arrested for the ‘dompas’. This Court needed to be for the people, unlike anything of the old order.

Thenjiwe Mtintso

then Chair of the Commission on Gender Equality

I was detained at Number Four on a number of occasions … My wife, a nursing sister, had to struggle to keep the home going. Two of my children were in tertiary education and graduated while I was in detention. I was obviously very excited to now be a member of the jury. If I had told the warders that one day I would be the Mayor of Johannesburg and on the jury to select a new Constitutional Court building, they would have killed me.

Isaac Mogase

then Mayor of Johannesburg

Naming Constitution Hill

Just prior to the competition brief going out, the National Monuments Council (NMC) managed to have the whole site declared a national monument. Up until then, only the Old Fort part of the prison complex had been declared a national monument. But from now on, any changes to any of the heritage buildings on site would be subject to NMC approval.

The intention of the declaration is to protect the cultural significance of the property. The NMC commits itself to the commissioning of comprehensive conservation survey of the to-be-declared complexes of buildings … to better understand the precinct’s heritage dynamic, both tangible and intangible.

JJ Bruwer

then Manager Northern Region, NMC

The very last decision that was made before the competition brief went out, was what the site would be called.

The question of a name for the precinct arose. I proposed that the whole area be called ‘Freedom Hill’ and that it be dedicated to freedom. Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson responded with ‘Constitution Hill’. I was a little dubious; I thought that was giving a kind of a legal slant to the place. But I’m very pleased that he made that suggestion. The word freedom is everywhere – you have ‘Freedom Square’ and ‘Freedom Park’, freedom this and freedom that. ‘Constitution Hill’ is much more specific and it gives it a very distinctive character. From then on we referred to the development as ‘Constitution Hill’.

Justice Albie Sachs

The launch of the competition

The competition was launched on 15 April 1997 at a formal ceremony in the Women’s Jail. During the ceremony, a partnership declaration was signed between the parties who were to be involved in the building of the court.

of innovation.

Jeff Radebe

then Minister of Public Works

Responses to the competition

The competition attracted an unexpected amount of interest, both locally and abroad.

The esteem in which our Constitutional Court is held, both by ourselves and in the international community, is aptly demonstrated by the interest which this competition attracted from across the world. In the international participants, whether in the competition or in the adjudication, we see the living reality of solidarity in struggle transformed into partnership for development and the entrenchment of democracy.

President Nelson Mandela

Five hundred and sixty architects and non-architects with a vision of what the Old Fort could become are working to meet the deadline of 6 November for the first phase of the competition. Few would have expected the unusual strength of local and international interest. Clearly, South Africa’s transition to democracy still causes international astonishment.

Carmel Rickard

journalist

As a result of the very positive experience this architectural competition has produced, the government recently agreed to adopt similar competitions as an alternative method for procuring designs for major government building projects.

Jeff Radebe

then Minister of Public Works

The five finalists

There were eventually 185 formal entries for the first stage of the competition. Forty were from other countries. The jury chose five finalists – entry numbers 13, 49, 50, 69 and 120. Each of the finalists was given detailed inputs by the jurists so as to develop their ideas for the second and final stage of the competition.

The five finalists’ entries were posted up on panels in the City Council’s Metro building. We’d limited the amount of space that people could use – I think it was three boards of a certain size. We didn’t want to give any advantage to people who could invest a lot of money on fancy models and so on. There was a great range of different concepts.

One project was manifestly African. It picked up on the idea of three huge concrete huts that would have been dramatic on the hill. Another that the architects liked very much was the citadel, not dissimilar to the Alhambra in Granada; a third was a bold glass and steel structure in the modern idiom. I called it Danish. A fourth was based on the theme of family, it had a warm and friendly character. I called it the three bears. The last one I called mish-mash because it wasn’t clear what the building would be like. I had a feeling that a woman was involved because little buttons were used to show where the trees would be. It had a sense of anticipation, democracy. I loved it and so did Thenji.

Justice Albie Sachs

And the winner is ...

The jury argued passionately about the merit of each of the entries. There was much discussion and debate. In the end, they chose the design that they felt captured the spirit of the brief and all that the building was to embody.

Everybody came up with something. It was not one man’s thought, but all the pieces put together. We were all equal. We all had a part in deciding. After some days, we agreed on one thing: the Court had to have a tinge of being African. This was because Johannesburg was an important city, the gateway into Africa.

Isaac Mogase

then Mayor of Johannesburg

The chances are good that the winning entry will become a watershed in the history of South African architecture and that it will make a contribution to the development of a new style in architecture.

Charles Correa

then Chief International Assessor

Dear Minister, We, the jury of the architectural competition for the Constitutional Court building, have the honour of informing you that we have selected entry number 120 as the winning entry.

- The Jury is of the opinion that the submission numbered 120 by the Competition Registrar is the winner of the competition. It has reached this conclusion because:

1.1 More than any other submission this one project has an image which is deemed to be appropriate to the aspirations of the competition brief.

1.2 It could be the pre-eminent building on the north slope of the site, not because of its monumental scale, but because it has the potential to express a new architecture which is rooted in the South African landscape, both physically and culturally.

1.3 The fragmented nature of the design disaggregates the built form to the scale of surrounding buildings. It is a conscious response to context and the need for construction methods which give opportunities for the exploitation of informal and alternative building procedures, technologies and material. This approach is more likely to succeed in revealing African trends than a self-conscious application of traditional stylistic elements or borrowing from European or historical building precedent.

Letter from the jury to Minister of Public Works Jeff Radebe

13 March 1998

The award ceremony

The winners were announced at a ceremony at the Old Fort on 8 April 1998. Everyone was delighted that when the identity of the finalists was finally revealed – four turned out to be South African and that the other was from Zimbabwe. The award ceremony was a joyous, fun occasion, and President Nelson Mandela made the most of it.

I feel distinctly uncomfortable on this occasion, and in fact I’m wondering what I’m doing here at all. Here I find myself sitting in the middle of a prison. I spent enough of my life there. As soon as the proceedings are over, I’m going to leave, just to make quite sure that nobody locks us up accidentally … And now I have the honour of presenting the winner of the competition. And the winner is … OMM Design Workshop and Urban Solutions!

President Nelson Mandela

at the award ceremony

I get quite emotional looking back at some of the pictures when we won the competition. We were amazed. We were in the right place at the right time. We were young South Africans who embraced what was going on in our country. That gave us a huge advantage over the international submissions.

Janina Masojada

winning architect

I am heartened by the fact that although there have been entries from all over the world, a South African design has won.

Justice Arthur Chaskalson

the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court

The Court’s physical foundations will rise from the horrific memories of torture and suffering which was perpetrated in the dark corners, cells and corridors of the Old Fort prison. Rising from the ashes of that ghastly era, this new institution will shine forth as a reminder for the future generation of our prevailing confidence and optimism that South Africa will never return to that abyss and indeed is a better place for all.

President Nelson Mandela

at the award ceremony

The winning design

The winning team comprised three architects and an urban designer – Janina Masojada, Andrew Makin, Erik Orts Hansen from OMM Design Workshop in Durban and Paul Wygers from Urban Solutions in Johannesburg. The team was young and passionate, and ready to take on the challenges the new Court presented.

We decided that if we’re going to do this thing, we’re going to do it to win. And we loved it. We loved the process; we loved the engagement, the stimulation of it. It embodied all the ideas that we believe in. We worked really hard, and we had the advantage that we were then at the stage where we had no dependents. We could work 18 hours a day, smoke three packets of cigarettes. It was a huge, huge thing in our lives. It was totally consuming.

Janina Masojada

winning architect

Two of the competition assessors – Charles Correa and Geoffry Bawa – were our architectural ‘heroes’ at university. Their thinking and achievements nourished our understanding of the nature of architecture in a diverse, ‘unresolved’ society like ours (and theirs). And with Albie Sachs it was clear that this competition was as much about dignity and the essence of what it means to be alive and human, as it was about architecture. Having Thenjiwe Mtintso, then head of the Commission on Gender Equality, on the jury, gave us confidence ‑ knowing the otherwise male jury was balanced by a powerful female voice.

Andrew Makin and Janina Masojada

winning architects

What set the winning design apart from the other entries was that it started from an urban design position. The design was an intervention that responded to the city around the Court, making connections across and beyond the site.

The brief called for a building in total isolation. No one had really considered how you were going to get to the building from the surrounding streets. And it was a derelict, overgrown and uninhabited environment. We designed a precinct rather than a building.

Janina Masojada

winning architect

Very early on I realised that there was only one place where you can put the Court – in juxtaposition with the Number Four prison. It was the only way you can ensure the thoroughfares across and through the Hill. Once we had decided on that and had established the journey between the two buildings, between the past and the present then all the other pieces fell into place.

Paul Wygers

urban designer

We had to ask ourselves what makes cities democratic? And the answer here relates to choices. Democratic cities offer people choices – which, in turn, relates to freedom of movement, freedom of access, and appropriate, mixed land use that meets the needs of the people and offers them a range of amenities and opportunities, conveniently.

Andrew Makin

Winning architect

The public response

The winning design attracted significant attention from the public, the media and the architectural profession.

This, the winning award, is architecture of a high order; subtle symbolism, sensitive planning for local conditions; an empathic response to a site of unique historic value; a quiet, assured, mature aesthetic. It has in the assessors’ words, ‘the potential to express a new architecture which is rooted in the South African landscape, both physically and culturally.’

Alan Lipman

heritage architect

From dream to reality

The competition allowed the winning designers to dream up a court. But architects are all too familiar with the gap between initially conceiving a design and actually making the building happen. While the jury loved the ideas and spirit of the building, they had noted areas of the design that were open to question. Now was the time to thrash out the realities. The designers, the judges and two architects from the jury who had been asked to stay on as advisors – Willie Meyer and Herbert Prins – worked together as a team going forward.

We came up to Johannesburg and met with the building committee, made up of some of the judges and some of the competition jury. They wanted us to assure them that in the course of design development the building would maintain its intentions and objectives. They said ‘You won because of your conceptual ideas, and because of your document but we still don’t know what the building looks like.’ They wanted us to agree that as part of the design work, some of the jury would continue their involvement in the project.

Janina Masojada

winning architect

Each section of the building was discussed with the relevant people ‑ not only the judges but members of the library staff, the administrative staff, and so on. The architects encouraged that kind of process, and it was extraordinarily exciting to be part of it.

Justice Kate O’Regan

Every aspect of the Court would be symbolic. The judges did not want a wall or fence around the Court because walls and fences create intimidating boundaries between people and institutions. The Court had to be a place where anybody, school children, people who go to work can easily pass through with no barriers. The judges wanted to be able to hear the children’s voices when they play in the streets of Hillbrow. The Court wanted to be the arch that connects the life between the city centre, Hillbrow and the suburbs.

The opening

The spectacular new Court building was opened on Human Rights Day, 21 March 2004. At the moving ceremony, President Thabo Mbeki described the building as an ‘architectural jewel’ and believed that the Court’s location made ‘the categorical statement that our country has broken with its past of despotic and tyrannical misrule’. He proclaimed the Court ‘a shining beacon of hope for the protection of human rights and the advancement of human liberty and dignity’.

Hundreds of dignitaries including 37 judges from around the world, South Africa’s own legal community, several Cabinet ministers and members of the Constitutional Assembly watched 27 children, all born in 1994, come up to the podium to recite the rights enshrined in the Constitution in the 11 official languages. The President then declared the seat of the highest Court in the land open.

The great wooden doors to the Court swung open to admit President Thabo Mbeki, the First Lady, Zanele Mbeki, Chief Justice Arthur Chaskalson, the Constitutional Court Justices, Speaker of Parliament, Frene Ginwala, Deputy Minister of Justice, Cheryl Gillwald, Johannesburg mayor Amos Masondo (once a political prisoner at the Old Fort) and Sam Shilowa, the Premier of Gauteng. The crowd applauded. In this acclaimed new building, the 11 judges would stand guard over the Constitution.

It is a building of light, a building of respect, a building of fragility but also of strength. It’s a building that reflects our history because it incorporates the degrading structure of a historical prison upon which the foundation is built.

Justice Edwin Cameron

When we moved here, I was appointed as a Senior Security. So, the responsibility became high. I think the idea of the architect for this building was transparency, but my job was to balance that with security concerns. You would think it would be scary to be next to Hillbrow but because of our policy of transparency people are able to see in and so people have a respect for the Court – so we have not had security concerns.

Godfrey Disemelo

head of security Constitutional Court