The Journey to

the Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights contained in the final Constitution of 1996 has a long history and is the realisation of decades of struggle for national liberation. Its origin lies in the courage and dreams of millions of ordinary people to overcome their suffering and one day live as free human beings in the land of their birth. Many of those who were imprisoned, tortured, banished and forced into exile never gave up on the dream of living in a country where all would enjoy basic human rights. Many gave their lives.

South Africans expressed their anger about the conditions under which they were forced to live in songs, newspapers, books; and also in a series of political documents – declarations, charters and a Bill of Rights – where they spelt out their vision of what the fundamental rights of every single South African should be. When Oliver Tambo established a Constitutional Committee to convert the ideals of the Freedom Charter into an operational plan for South Africa in 1986, Pallo Jordan reminded the ANC that it had first adopted a Bill of Rights in 1923. He also brought key documents and declarations drawn up on the African continent and internationally to the table as inspiration and to make use of the invaluable jurisprudence that had evolved over decades. In this section you can explore some of the important documents that informed the South African Bill of Rights.

The documents

What informed our generation, tasked with continuing with that struggle in the writing of the Constitution, was to learn from those who had gone before us.

Mavivi Myakayaka-Manzini

then ANC member of the Constitutional Assembly

The Bill of Rights is the product of our history, the demands of earlier generations for equal rights, the influence of hundreds of individuals and NGOs, international expertise, technical advice and the submissions of ordinary South Africans. All these coalesced into a document which is proudly owned and fiercely defended by all South Africans.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

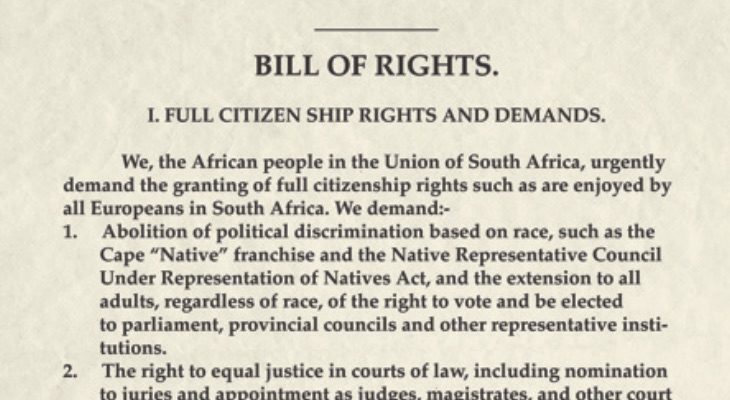

1. The 1923 African Bill of Rights

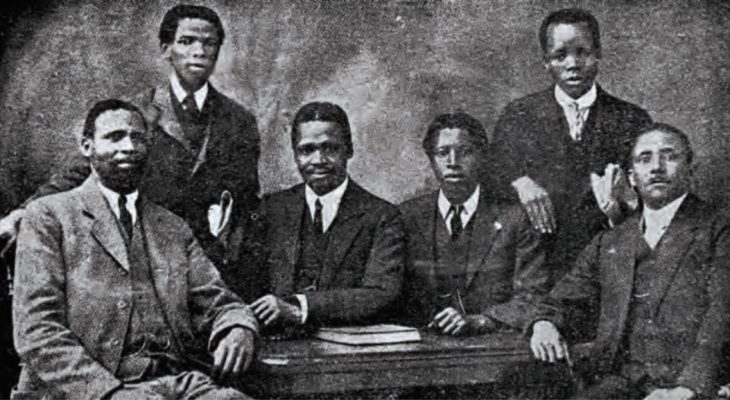

The members of the SANNC deputation that left for Britain to plead for the recognition of rights for black people by the Union after the end of World War I, included Thomas Levi Mvabaza, Richard Victor Selope Thema, Rev. Henry Ngcayiya, Sol Plaatje and Josiah Tshangana Gumede – all founding members of the ANC. National Library of South Africa, Cape Town

Between March and June 1919, a deputation of members from the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) left for Britain to plead for the recognition of rights for black people by the Union after the end of World War I. Three years later, during the annual convention of the SANNC in Bloemfontein held on 28-29 May 1923, the delegates adopted a resolution on a bill of rights. This early African Bill of Rights urged the South African and British governments to recognise the rights of black South Africans. It called for equal treatment of all people, equal access to land, direct representation and voting rights as reflected in these clauses:

Clause 1: That the Bantu inhabitants of the Union have, as human beings, the indisputable right to a place of abode in this land.

Clause 2: That all Africans have, as the sons of this soil, the God-given right to unrestricted ownership of the land in this, the land of their birth.

Clause 3: That the Bantu, as well as their coloured brethren, have, as British subjects, the inalienable right to enjoyment of those British principles of the liberty of the subject, justice, equality for all classes in the eyes of the law that have made Great Britain one of the greatest world powers.

Clause 5: That the African people should be accorded direct representation by members of their own race in all legislative bodies of the land, otherwise, there would be ‘no taxation without representation.

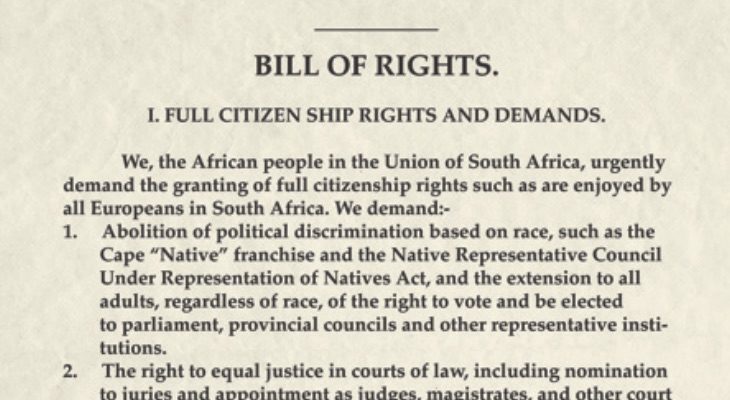

2. The 1943 African Claims in South Africa Document

The African Claims Document, which included a Bill of Rights, demanded that all South Africans be granted the same rights and freedoms as those enshrined in the Atlantic Charter of August 14, 1941. This charter, proclaimed by American President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was a statement of the peace aims of the allies and an affirmation of certain common principles ‘on which they based their hopes for a better future for

the world’.

In December 1942, the ANC President, Dr. A.B. Xuma, appointed a committee to interpret the Atlantic Charter from an African point of view. The committee was chaired by Professor Z.K. Matthews and consisting of prominent African professionals and intellectuals of varied political views. Their report entitled ‘Africans’ Claims in South Africa’ contained a Bill of Rights and was unanimously adopted by the ANC annual conference on 16 December 1943. This statement of the aspirations of the African people was one of the ANC’s most important documents, inspiring the Freedom Charter of 1955 and also influencing the

final Constitution.

I call upon chiefs, ministers of religion, teachers, professional men, men and women of all ranks and classes to organise our people, to close ranks and take their place in this mass liberation movement and struggle, expressed in this Bill of Citizenship Rights until freedom, rights and justice are won for all races and colours to the honour and glory of the Union of South Africa whose ideals – freedom, democracy, Christianity and human decency – cannot be attained until all races in South Africa participate in them.

Dr. A.B. Xuma

Then ANC President, 1943

When Dr. Xuma requested an interview with General Jan Smuts, the Prime Minister of South Africa, to discuss the Africans Claims in South Africa document, Smuts refused saying that he was “not prepared to discuss proposals which are wildly impracticable”. Smuts’s grand public rhetoric around freedom in the world was much bolder than the concessions he was prepared to make at home. A delegation went to New York to convince world leaders that a permanent peace in South Africa was only possible if the claims of all South Africans are recognised.

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

3. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

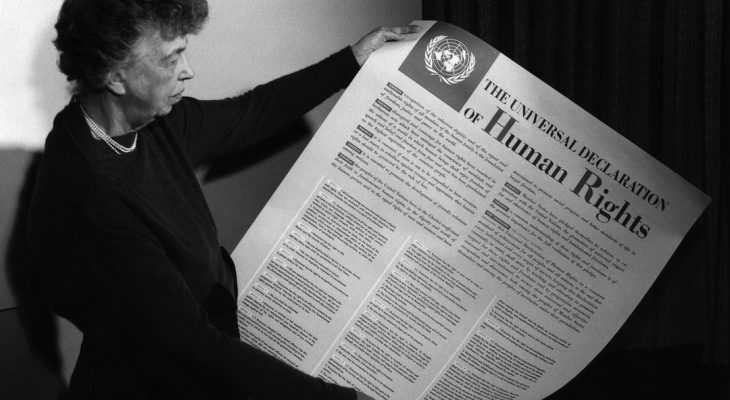

After the end of World War II, a series of conventions and declarations began to communicate the issue of universal human rights. The United Nations (UN) was established in 1945, partly to continue the work of the dissolved League of Nations, in response to proposals for the creation of a new world body to monitor relations between states and to promote and encourage respect for human rights through international cooperation.

The UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration on 10 December 1948 as a direct result of the struggle against the racist and inhumane ideas of Nazism and fascism in Europe that had led to World War II. The Commission on Human Rights that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was made up of 18 members from diverse global, political, cultural and religious backgrounds and perspectives. Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt, chaired the UDHR drafting committee. Other women also played essential roles in shaping the document. The document was drafted in less than two years.

It was followed by the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 1966 when the decolonisation process was at its height and when new and more wide-ranging concepts of human rights were being accepted.

I perceived clearly that I was participating in a truly significant historic event in which a consensus had been reached as to the supreme value of the human person, a value that did not originate in the decision of a worldly power, but rather in the fact of existing … In the Great Hall … there was an atmosphere of genuine solidarity and brotherhood among men and women from all latitudes, the likes of which I have not seen again in any international setting.

Hernán Santa Cruz of Chile

Then member of the drafting Sub-Committee

Some of the women that shaped the UDHR. Left to right: Angela Jurdak (Lebanon), Fryderyka Kalinowska (Poland), Bodgil Begtrup (Denmark), Minerva Bernardino (Dominican Republic), and Hansa Mehta (India), delegates to the Sub-commission on the Status of Women, New York, May 1946. National Archives and Records Service of South Africa

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

4. The 1954 Women’s Charter

The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) adopted the Women’s Charter at its inaugural conference on 17 April 1954. The charter proposed a plan of action for the organisation which catered for all women regardless of race and called for full equality with men. Its preamble declared: “We, the women of South Africa … African, Indians, European and Coloured, hereby declare our aim of striving for the removal of all laws, regulations, conventions and customs that discriminate against us as women …”

The Charter was used to produce a pamphlet entitled “What Women Want” submitted to the Congress of the People’s organising committee when they were drafting the Freedom Charter which was adopted in 1955. The Charter became a source of inspiration years later when the Women’s Charter for Effective Equality was drafted in 1994.

The Women’s Charter called not only for equality with men but also appealed for equality within national liberation movements, organisations and trade unions.

Extracts from the Women’s Charter Adopted at the Founding Conference of the Federation of South African Women Johannesburg,

17 April 1954

Preamble: We, the women of South Africa … African, Indians, European and Coloured, hereby declare our aim of striving for the removal of all laws, regulations, conventions and customs that discriminate against us as women …

A Single Society: We women do not form a society separate from the men. There is only one society, and it is made up of both women and men. As women we share the problems and anxieties of our men and join hands with them to remove social evils and obstacles to progress.

Women’s Lot: We women share with our menfolk the cares and anxieties imposed by poverty and its evils. As wives and mothers, it falls upon us to make small wages stretch a long way. It is we who feel the cries of our children when they are hungry and sick. It is our lot to keep and care for the homes that are too small, broken and dirty to be kept clean. We know the burden of looking after children and land when our husbands are away in the mines, on the farms, and in the towns earning our daily bread.

Our Aims

- The right to vote and to be elected to all state bodies, without restriction or discrimination.

- The right to full opportunities for employment with equal pay and possibilities of promotion in all spheres of work.

- Equal rights with men in relation to property, marriage and children, and for the removal of all laws and customs that deny women such equal rights.

- For the development of every child through free compulsory education for all; for the protection of mother and child through maternity homes, welfare clinics, creches and nursery schools; through proper homes for all, and through the provision of water, light, transport, sanitation …

- For the removal of all laws that restrict free movement, that prevent or hinder the right of free association and activity in democratic organisations …

- To build and strengthen women’s sections in the National Liberatory movements, the organisation of women in trade unions, and through the peoples’ varied organisations …

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

5. The 1955 Freedom Charter

On 25 June 1955, the Congress of the People gathered in Kliptown near Johannesburg to adopt the Freedom Charter. This Charter, compiled from thousands of submissions from South Africans across the country, created a vision for an apartheid-free country with a statement of core principles. The declaration in the Charter, ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white’, spoke of an inclusive nationalism, of a new nation waiting to be born. Many speakers on the Freedom Charter stated that the road might be long, but a united democratic front was the only solution.

The Freedom Charter was passed unanimously as the gathered crowds chorused ‘Afrika!’ and ‘Mayibuye!’ International messages of support added to the feeling of optimism on the day. The meeting pledged: ‘These freedoms we will fight for, side by side, throughout our lives until we have won our liberty.’ The words, ‘the People Shall Govern’, rang out across the following decades. The Charter is the greatest source for the Bill of Rights in South Africa.

More than 3 000 delegates braved police intimidation to assemble and approve the final document. They came by car, bus, truck and foot. Although the overwhelming number of delegates were black, there were more than three hundred Indians, two hundred coloureds and one hundred whites.

Nelson Mandela

then President of the ANC Youth League, describing this momentous event in his autobiography

It should have been plain to the architects of Union that by excluding from the orbit of democracy the majority of the population, the non-whites, they were laying a false foundation for the new state and making a mockery of democracy to call such a state democratic.

Albert Luthuli

then ANC President, in his message read to the Congress, 1955

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

Photographs

6. The 1959 Azanian Manifesto

The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) was formed by a group of dissatisfied ANC members in Orlando, Soweto, on 5 and 6 April 1959. The breakaway group was led by members of the so-called Africanist movement including Robert Sobukwe, Potlako Leballo, Ashby Solomzi, Peter Mda and Abednego Bhekabantu Ngcobo. The Africanists rejected the Freedom Charter, mainly because of the guarantees it contained for minority rights. These guarantees, they felt, would entrench minority domination. The Africanists believed that the land which the ‘white settlers had stolen’ from the indigenous people should be returned to South Africans. The PAC adopted the Azanian Manifesto in 1959. It includes, among others, the following important aims and principles:

- The struggle for national liberation must be against racist capitalism, which imprisons the people of Azania to the advantage of the small minority of white capitalists and their allies.

- Only the destruction of the system of racial capitalism can destroy apartheid.

- The black working class, inspired by a revolutionary awareness, is the driving force in the struggle.

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

Documents

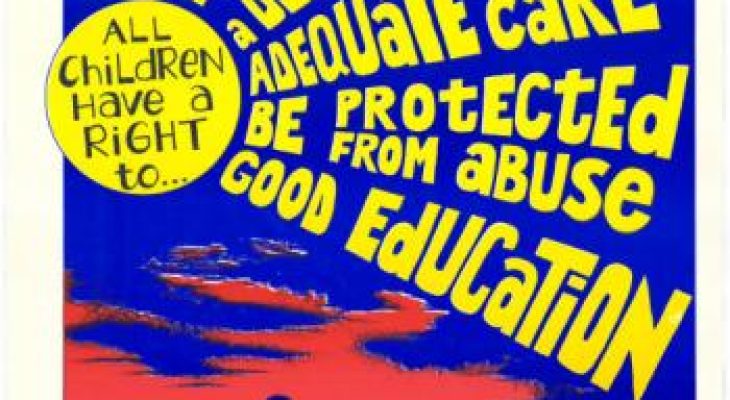

7. The 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child

In 1924, the League of Nations adopted the Geneva Declaration, a historic document that recognised and affirmed for the first time the existence of rights specific to children and the responsibility of adults towards children. A year after its formation in 1945, the United Nations took over the Geneva Declaration and following the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the UN expanded the declaration. A second Declaration of the Rights of the Child was drafted on 20 November 1959 and it was adopted unanimously by all 78 Member States of the United Nations General Assembly in Resolution 1386 (XIV). It marked the first major international consensus on the fundamental principles of children’s rights. It declared that: “The child is recognised, universally, as a human being who must be able to develop physically, mentally, socially, morally, and spiritually, with freedom and dignity.”

The Declaration of the Rights of the Child comprises ten key rights:

1. The right to equality, without distinction on account of race, religion or national origin.

2. The right to special protection for the child’s physical, mental and social development.

3. The right to a name and a nationality.

4. The right to adequate nutrition, housing and medical services.

5. The right to special education and treatment when a child is physically or mentally handicapped.

6. The right to understanding and love by parents and society.

7. The right to recreational activities and free education.

8. The right to be among the first to receive relief in all circumstances.

9. The right to protection against all forms of neglect, cruelty and exploitation.

10. The right to be brought up in a spirit of understanding, tolerance, friendship among peoples, and universal brotherhood.

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

Photographs

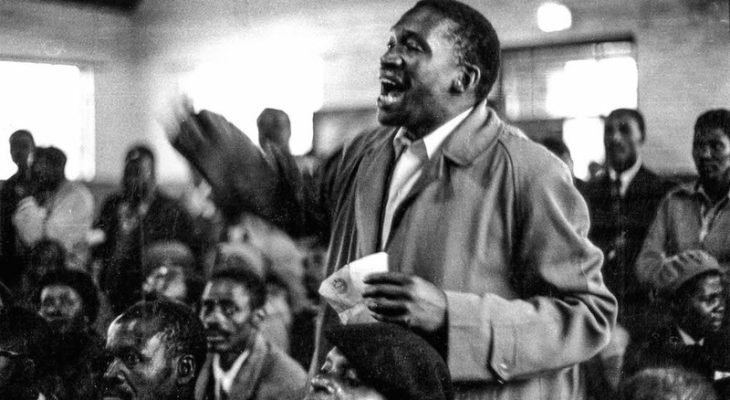

8. The 1961 Resolutions of the All-in-Conference

Chief Albert Luthuli and other ANC leaders convened a Consultative Conference of African leaders in Orlando, Johannesburg, in December 1960. The purpose was to consider united action following the banning of the ANC and PAC, several months of a state of emergency, as well as protests against a whites-only referendum on declaring a Republic. The Consultative Conference decided to call an All-in Conference and set up a Continuation Committee.

The All-in African Conference, held in Pietermaritzburg on 25 and 26 March 1961, was attended by 1 398 delegates from all over the country, even though the government had arrested a majority of the members of the Continuation Committee and took other measures to hinder the conference.

Nelson Mandela addressed the Conference where the following resolutions were made:

- WE DECLARE that no Constitution or form of Government decided without the participation of the African people who form an absolute majority of the population can enjoy moral validity or merit support either within South Africa or beyond its borders.

- WE DEMAND that a National Convention of elected representatives of all adult men and women on an equal basis irrespective of race, colour, creed or other limitation, be called by the Union Government not later than May 31st, 1961; that the Convention shall have sovereign powers to determine, in any way the majority of the representatives decide, a new non-racial democratic Constitution for South Africa.

- WE RESOLVE that should the minority Government ignore this demand of the representatives of the united will of the African people –

- We undertake to stage country-wide demonstrations on the eve of the proclamation of the Republic in protest against this undemocratic act.

- We call on all Africans not to cooperate or collaborate in any way with the proposed South African Republic or any other form of Government which rests on force to perpetuate the tyranny of a minority, and to organise and unite in town and country to carry out constant actions to oppose oppression and win freedom.

- We call on the Indian and Coloured communities and all democratic Europeans to join forces with us in opposition to a regime which is bringing disaster to South Africa and to win a society in which all can enjoy freedom and security.

- We call on democratic people the world over to refrain from any cooperation or dealings with the South African government, to impose economic and other sanctions against this country and to isolate in every possible way the minority Government whose continued disregard of all human rights and freedoms constitutes a threat to world peace.

- WE FURTHER DECIDE that in order to implement the above decisions, Conference elects a National Action Council.

- Instructs all delegates to return to their respective areas and form local Action Committees.

9. The 1981 African Charter on Human and People’s Rights

The Eighteenth Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) made an historic step toward the protection of human rights in Africa by adopting the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights in Nairobi, Kenya in 1981. The Charter represents the culmination of a two-year drafting process that took place in Banjul, The Gambia, from June 1980 to January 1981 under the leadership of the OAU – now the African Union. The purpose of the Charter was to create an instrument that sets human rights standards – while recognising African values and traditions – and protects human rights and basic freedoms on the African continent. As of 2019, 53 states have ratified the Charter. The preamble stresses the importance of economic, social, and cultural rights:

“[I]t is henceforth essential to pay particular attention to the right to development and that civil and political rights cannot be dissociated from economic, social and cultural rights in their conception as well as universality and that the satisfaction of economic, social and cultural rights is a guarantee for the enjoyment of civil and political rights.”

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

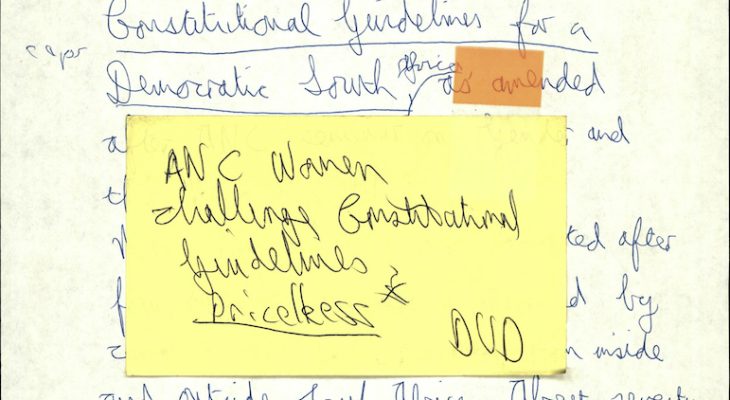

10. The 1988 ANC Constitutional Guidelines

The ANC’s Constitutional Guidelines are contained in a document issued by the ANC National Executive Committee in 1988. The guidelines converted the visionary Freedom Charter into a constitutional reality by setting out broad proposals on what the foundations of government in a united, non-racial and democratic SA should be. The Guidelines were developed over a period of years with the active participation of the ANC Constitutional Committee. Numerous meetings, debates and seminars were held specifically to analyse and refine the text.

The Guidelines confirmed the ANC’s commitment to multi-party democracy and a Bill of Rights that could be enforced. It also contained a progressive social outline in point form of the ANC’s views on the nature of the state, the voting system, the basis of the economy, gender relations and workers’ rights and gave an important position to a Bill of Rights. The Guidelines further confirmed the ANC’s commitment to combating sexism, eliminating inequalities based on sex, and guaranteeing fundamental rights regard-less of sex. (They said nothing explicit, however, to guarantee gay rights, or to prohibit discrimination based on

sexual orientation.)

While representing a firm statement of broad ANC positions, the Guidelines were never intended to be taken as a final and clear-cut prescription for the future. Rather, they were submitted to the ANC membership and the people of SA as a whole for debate, commentary, criticism and refinement.

The Guidelines embodied the fundamental principles of the Freedom Charter and confirmed the ANC’s commitment to multi-party democracy, an enforceable Bill of Rights, and progressive social and economic reforms.

Zola Skweyiya

Then Chair of the ANC Constitutional Committee, 1991

We felt that as a matter of principle, a constitution should emerge from a democratically constituted assembly, representing the whole South African people.

Albie Sachs

then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

The comments that were received [during the seminars and debates] ranged from insistence that the issue of women’s rights be treated more extensively, to vigorous proposals that social and economic rights be spelt out more explicitly and that the question of access to the land receive fuller attention. The Committee also received proposals from a wide range of organisations associated with the UDF including those concerned with such issues as ecology, gay and lesbian rights and rights of the disabled. They also consulted proposals on worker’s rights from COSATU, the Communist Party and other organisations involved in worker’s struggles.

Zola Skweyiya

Then Chair of the ANC Constitutional Committee, 1991

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

11. The 1988 ANC Bill of Rights

In the ANC’s January 8 statement of 1987, the organisation declared its commitment to a Bill of Rights that was justiciable – meaning that it must be protected by the courts. Such a document would ‘guarantee equal rights for all citizens and defend each and every one of us against the kinds of tyranny and abuse which have flowed daily from the apartheid state’.

The Constitutional Committee of the ANC asked Professor Kader Asmal and Albie Sachs – who had months before been blown up by a car bomb in Mozambique – to write the first draft of the Bill of Rights. In 1990, once the ANC’s Constitutional Committee moved from Lusaka to South Africa, the Committee continued working on drafting a Bill of Rights for the new democracy that could be thrashed out during negotiations. They were clear that for a Bill of Rights to be acceptable by everyone, it had to be in Professor Kader Asmal’s words, “openly debated, transparent in its procedures and adopted by a mandate of the people. Only a democratically elected body had the moral and legal authority to adopt such a vital constitutional document … The landscape of South Africa is littered with bogus charters, as in the Ciskei and Bophuthatswana, and we should not limit our future rights through a limited party-political document.” At this point, the ANC’s intention was to set out its vision and policy.

The Bill of Rights is the fundamental anti-apartheid document. It guarantees equal rights for all citizens and defends each and every one of us against the kinds of tyranny and abuse which flowed daily from the apartheid state.

Zola Skweyiya

Then Chair of the ANC Constitutional Committee

The Bill of Rights was Oliver Tambo’s strategic response to all these [ideas] of group rights that were being proposed as constitutional solutions to the crisis in South Africa. The idea [behind it was to assert that as a South African] you have a right to feel you’re a citizen, to go to court, to vote, to stand for parliament, to be in government, to do everything like everybody else not because you’re white, [but] because you’re a person like everybody else. That was the strategic answer.

Albie Sachs

then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

In the 1980s, the ANC was the first major political formation in South Africa to commit itself firmly to a Bill of Rights, which we published in November 1990. This milestone gave concrete expression to what South Africa could become. It projected a democracy in which the government, whomever they may be, will be bound by a higher set of rules, embodied in a constitution, and will not be able to govern the country as it pleases.

President Nelson Mandela

Inaugural Speech, 1994

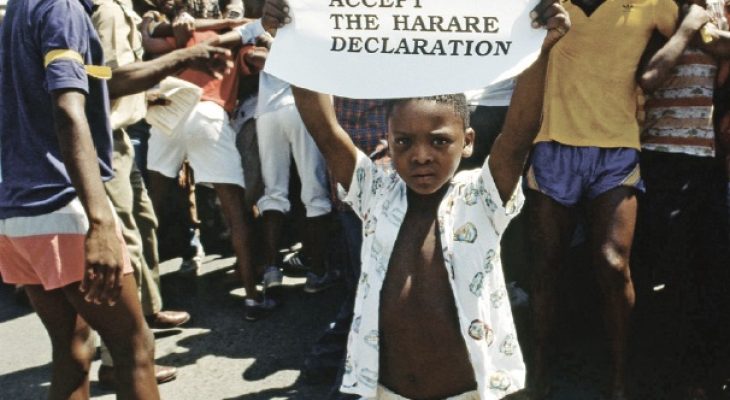

12. The 1989 Harare Declaration

The Declaration of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) ad hoc Committee on Southern Africa on the question of South Africa; Harare, Zimbabwe – The Harare Declaration of 21 August 1989.

The Harare Declaration affirmed the ANC’s commitment to genuine negotiations to reach a political settlement in South Africa. Statement 14 in the Declaration’s Statement of Principles, states: “We believe that a conjuncture of circumstances exists which, if there is a demonstrable readiness on the part of the Pretoria regime to engage in negotiations genuinely and seriously, could create the possibility to end apartheid through negotiations. Such an eventuality would be an expression of the long-standing preference of the majority of the people of South Africa to arrive at a political settlement.” Also central to the declaration was the demand that a duly elected and representative body should be mandated to draft a new Constitution for South Africa.

The declaration arose at a time when the apartheid government was asserting its control through increasing violence. In the meantime, ANC President, Oliver Tambo, realising that a negotiated solution to the conflict in South Africa might become the only way forward, pursued a diplomatic strategy to convince the frontline states and the OAU to accept a process of negotiations and the terms on which it would happen. He travelled around the continent consulting and seeking support from African leaders.

The Harare Declaration was ultimately drafted by an internal committee in the ANC based on these consultations as well as on input from the Mass Democratic Movement, and significantly by the Mandela Document. Mandela had managed to smuggle a copy of his document to ANC headquarters in Lusaka, where it was endorsed by the organisation. It contained a vision for the transition to democracy and provided the blueprint for the negotiations process that would lead South Africa to a new political dispensation. Once Mandela had been consulted and Oliver Tambo and Thabo Mbeki had lobbied African leaders, the declaration was finalised. The Declaration made it clear that certain conditions would have to create the right climate for negotiations.

Sadly, Oliver Tambo, who was the chief steward of the document, had a stroke and was not able to present the declaration at the meeting in Harare where it was adopted by an OAU ad-hoc committee on South Africa on 21 August 1989. Thereafter, the declaration was adopted by the Commonwealth and the United Nations General Assembly.

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

13. The Workers Charter of 1990

During 1985, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the broader labour movement debated if they should adopt the Freedom Charter to guide their political programmes and alliances. Many unionists felt that the Freedom Charter did not sufficiently cover the interests of workers, especially since the charter did not include one of the most basic worker rights – the right to strike. A Workers Charter was, therefore, proposed as a more radical alternative to the 1955 document to prioritise the interests of the working class and pave the way towards socialism. The debate became highly polarised with some arguing that unions should fight political struggles away from the workplace and others insisting that the struggle for national liberation could not be divorced from the struggle against capitalist exploitation.

The [Freedom Charter] is a capitalist document. We need a Workers Charter that will say clearly who will control the farms … factories, the mines … There must be a change of the whole society.

Moses Mayekiso

FOSATU, 1985

At the second congress of COSATU in 1987, a number of unions endorsed the Freedom Charter as their guiding document. Others at the congress – the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU) – developed their own Workers Charters.

Over the next years, the idea of a single Workers Charter gained more strength and at COSATU’s third congress on 12 July 1989, a resolution was tabled for a Workers Charter to be drawn up. A Workers Charter Campaign was launched to develop a Charter that would ‘articulate the basic rights of workers’, be ‘guaranteed by the constitution of a people’s government’. This culminated in the adoption of The COSATU Platform of Worker Rights at a COSATU Special Congress in September 1993.

The Workers Charter was used by COSATU as a base document in negotiating workers’ rights during the negotiated transition to democracy. Calls for the Draft Workers Charter to be appended to the final Constitution were made in two public submissions to the Constitutional Assembly in 1996. Traces of the Workers Charter can be found in Section 23 of the final Constitution.

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

Documents

14. The 1994 Women’s Charter for Effective Equality

At the start of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa, a wide range of women’s organisations felt that women were inadequately represented at the negotiating table. The Women’s National Coalition (WNC), comprising seventy organisations and eight regional coalitions, became a very important and vocal advocacy group which dramatically increased the visibility of women at this time.

The WNC were responsible for drafting the Women’s Charter. The process included a great number of conferences, workshops, seminars and consultations to discuss the aim of drawing up the Charter. These went hand in hand with a nation-wide participatory research project and coalition campaign to elicit women’s demands for the Charter dubbed ‘Operation Big Ears’. Frene Ginwala, co-convenor of the WNC, argued for broad consultation with women at the grassroots level, urging the coalition to “grow ‘big ears’ that reach the farthest corners of our land. Let us encourage women to speak of their problems and how they understand and experience gender oppression in their daily lives.”

The draft charter was presented to the February 1994 Women’s Convention, and then revised by a committee set up by the conference, including the original drafters. This charter contained women’s visions for a democratic, non-sexist and non-racial South Africa. It called for equality in all spheres. The word ‘effective’ in the title of the 1994 Charter was specifically chosen to describe the kind of equality envisioned: limited to not just political and legal equality but also to women’s social and economic power.

Although the Charter was finalised too late for the Interim Constitution, the demands articulated in this Charter were ultimately incorporated into the final Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

This Charter gives expression to the visions and aspirations of South African women … We call for respect and recognition of our human dignity and a change in our status and material conditions in a future South Africa.

The Women’s Charter of 1994

The state may not unfairly discriminate … against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.

Section 9 – the Equality Clause of the Constitution

EXPLORE THE ARCHIVE

15. The 1993 Bill of Rights in the Interim Constitution

The negotiations – first during CODESA and then during the Multi-Party Negotiating Process (MPNP) – were at times deadlocked, suspended and also broken off. After the rollercoaster ride, there was great jubilation when an Interim Constitution was finally agreed upon. It was passed on 22 November 1993 by the last Parliament under the old order. It was South Africa’s fourth Constitution but its first democratic one:

This is a firm foundation upon which the dreams of millions of South Africans could be realised.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Multi Party Negotiating Process (MPNP)

The Interim Constitution of 1993 set in place a revolutionary principle in South Africa’s constitutional history – that the Constitution would be supreme and there would be judicial review to enforce it. It also set the framework for the writing of the final Constitution of 1996 by outlining 34 Principles with which the final constitution had to comply. These Principles could not be amended in any way.

This is a transitional constitution which is not cast in stone. What is cast in stone are the Constitutional Principles which we are very happy with and it is around those Constitutional Principles that the Constitutional Assembly will draft the [final] Constitution.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Multi Party Negotiating Process (MPNP)

One of the most celebrated features of the Interim Constitution is its Bill of Rights. At last, this Bill of Rights provided protection of equal rights for all and expressed the long-held dreams of liberation movements across the decades. The Interim Constitution set up new structures to protect the rights under the Bill of Rights including: the Constitutional Court; the Human Rights Commission; the Public Protector; the Land Claims Court.

The rights in the Interim Constitution only worked ‘vertically’, meaning that only government structures had to follow them. In the final Constitution, the rights also worked ‘horizontally’ meaning that the government as well as all private individuals, companies or other bodies have to follow the Bill of Rights.

Constitutional Assembly Collection, Department of Justice, Civil Society Submissions part 4, p, 599

https://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/history/SUBMISS/INDsc-part04.pdf

Parliament of the Republic of South Africa (2018) Theme Committee Book Series 1-6.

Segal, L and Cort, S (2011) One Law One Nation, Jacana Publishers.

Transcript of Dr Xuma’s speech available at: https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/anc/1943/claims.htm#CHARTER