The story of the writing of the Constitutional Guidelines

1986-1988

Albie Sachs Collection, UWC Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archives

The Constitutional

Guidelines Committee:

The Committee was based in Lusaka, and worked directly with Tambo and reported to a sub-committee of the National Executive Committee (NEC), the highest decision-making body in the ANC. It was initially chaired by Jack Simons, and then later by Zola Skweyiya who was initially deputy chair. It included Jobs Jobodwana (secretary and minute taker), Albie Sachs (rapporteur), Kader Asmal, Penuell Maduna, and Ted Phakane. Brigitte Mabandla joined later. These ANC activists were all lawyers and constitutional scholars, and each had an extraordinary life story.

Listen to Albie Sachs reflect on the Constitutional Committee

The three kinds

of constitutions:

Sachs, as rapporteur of the Constitutional Committee, presented three constitutional models to the NEC. The first was the classical American-type constitution that provided for the separation of powers and placed limits on the powers of government. The second was a People’s Power constitution of the kind that existed at that stage in Mozambique, Angola, Cuba, and the Soviet Union. This model consolidated revolutionary power and provided for a designated party to lead society and direct the institutions of state and government. The third model was termed a ‘post-dictatorship’ constitution of the kind that Portugal and Nicaragua had adopted after the overthrow of fascist regimes. This model provided for a multi-party democracy, coupled with strong programmes of social reform.

Multi-party

democracy:

It was this third post-dictatorship model that was later formally adopted by the NEC. By opting for a multi-party democracy, as envisaged by the Freedom Charter, and by adopting an emancipatory Bill of Rights coupled with affirmative action, the NEC set the context in which the constitutional debates were to take place.

The debates:

Extensive discussions took place between the Constitutional Committee and the sub-committee of the NEC consisting of Pallo Jordan, Joe Slovo, and Simon Makana. One key issue was whether or not the Guidelines that were being written were too ‘bourgeois’ – that is, did they reflect too much of a classical liberal constitution that protected the status quo? The Constitutional Guidelines were eventually agreed to and presented to Tambo who proposed a number of revisions before they were adopted by the NEC for presentation.

The 1988

In-House Seminar:

This important seminar was attended by 70 delegates from ANC units throughout the world , from Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and from diplomatic missions. There were many discussion groups and a revised version of the Constitutional Guidelines came out of this seminar.

Combating

sexism:

One of the highlights of the seminar was an intervention by Ruth Mompati who said that the Guidelines spoke about 300 years of colonial domination and racial discrimination, but said nothing of a millennium of gender domination; it included a positive section of rights for women, but said nothing of combating sexism. This was then worked on.

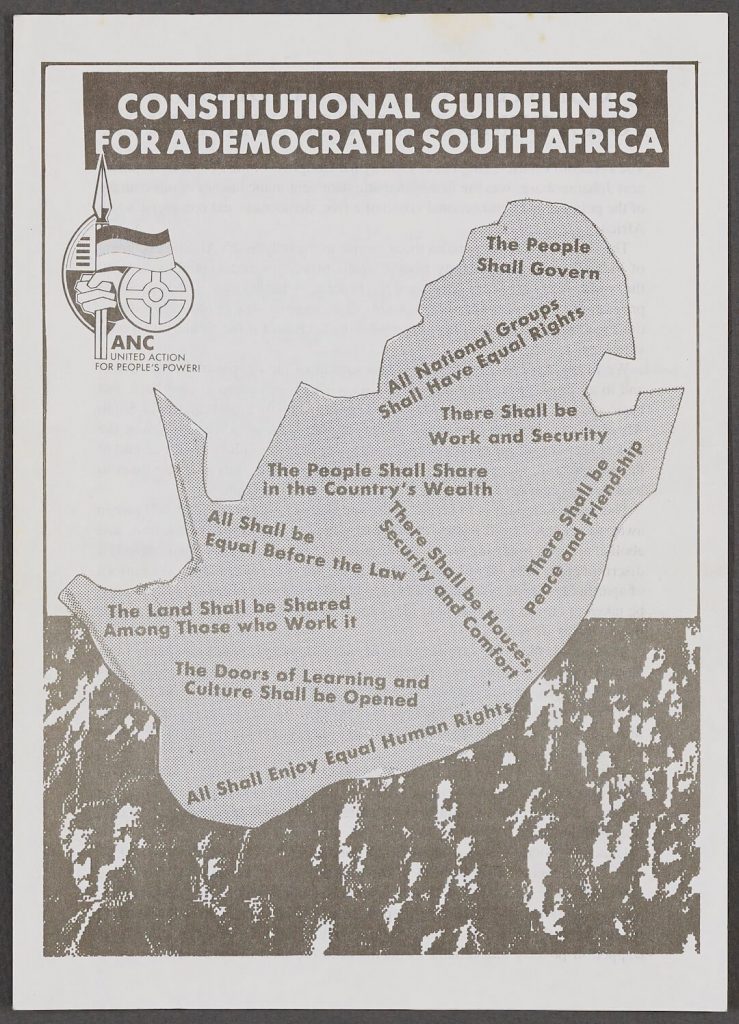

The Constitutional

Guidelines:

The revised Guidelines were sent to South Africa and the rest of the world inviting comments. At their heart was the principle often expressed by Oliver Tambo that, “You protect people from abuse not because they’re black, not because they’re white, not because they’re in the majority, not because they’re in the minority, but because they’re human beings.” The Guideline’s principles were later included in the Harare Declaration and became the foundational principles for the South African Constitution.

In their own words

“Our Committee didn’t have a photocopy machine. All we had was somebody who could type out a master copy on waxed paper from our handwritten manuscripts, and then we would have to cyclostyle those old wax things, ink all over the place, smudging the limited number of copies you could produce. I spent months pleading with supporters in the United States who were willing to die for the South African struggle but who weren’t willing to donate a photocopy machine.

And suddenly we leapt into this new phase, with an attractively produced document! It was produced by the ANC press / information committee in London headed by Gill Marcus. Her family had a sandwich outlet in Holborn in the morning and ran a printing press for the ANC in the afternoon.”

“The Committee received proposals from a wide range of organisations associated with the UDF including those concerned with such issues as ecology, gay and lesbian rights and rights of the disabled. They also consulted proposals on worker’s rights from COSATU [Congress of South African Trade Unions], the Communist Party and other organisations involved in worker’s struggles.”

-Zola Skweyiya, then Chair of the ANC Constitutional Committee, 1991

“The camaraderie among all of us, the mutual respect, the opportunity to debate a whole lot of things pertaining to law and order, human rights etc. and the opportunity to engage in those discussions I sorely miss even today.”

“The Guidelines have to be seen as a weapon, an instrument. And like any struggle, as our military comrades are always telling us, you have to prepare your terrain, you have to know your weapons and be scientific about these things … And just like you have to study limpet mines, you have to study different constitutions, different forms of government. We have to know these things in order to convert them into weapons that we can use effectively. Hence this seminar.”

“So women started saying, how do we amend the guidelines so that they deal with issues of gender? And the seminar came out of that. Now the whole initiative has been carried right through to the point that the ANC has adopted a position on the emancipation of women.”

“We believe it is necessary to place an obligation on the state to end sexism, in a similar manner to the obligation to end racism. Otherwise, the equal rights accorded to women can be no more than rhetoric … A recommendation made was that any law, custom or practice that discriminates against women should be held to be unconstitutional … Similarly, proposals were made regarding the family: the need to recognise various types of family systems, and to remove the structural subordination of women in any new family law.”