Events leading to the civil war

1990 - 1994

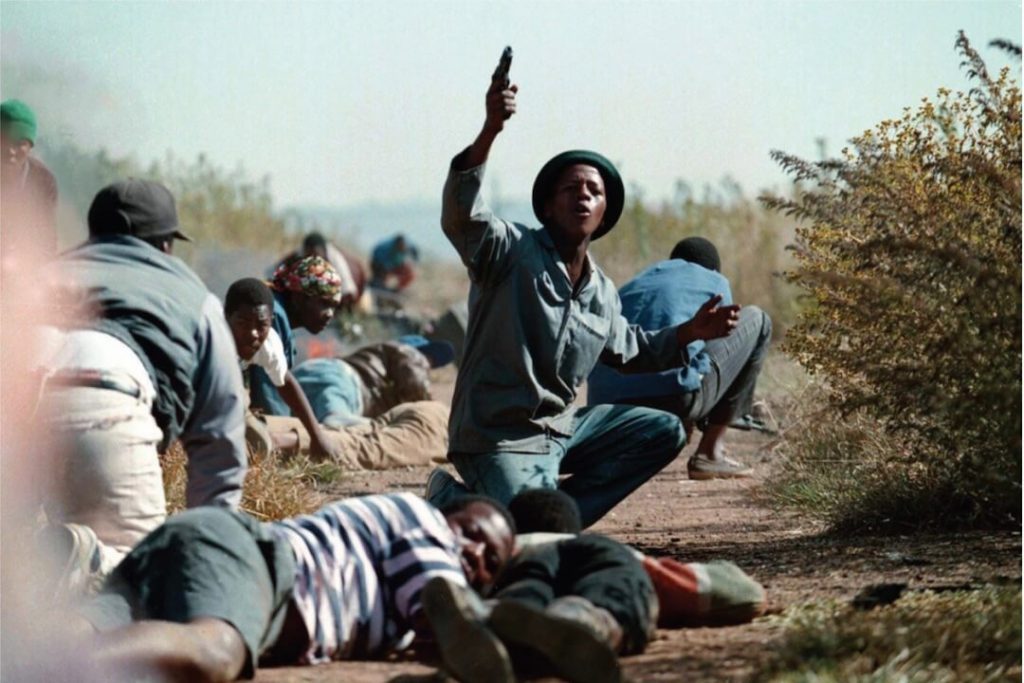

Source Unknown

The Inkatha

Freedom Party (IFP):

In 1975, Mangosuthu Buthelezi founded a Zulu cultural movement, Inkatha Yenkululeko Yesizwe, the forerunner to the IFP. Buthelezi, once a member of the ANC Youth League, initially supported the ANC and popularised its symbols and traditions. Within a few years, however, the interests and policies of the two parties had diverged. The ANC accused Buthelezi of co-operating with the apartheid government and betraying the liberation struggle by opposing the armed struggle and sanctions. It denounced Buthelezi’s glorification of tribal identity which was at odds with the broad nationalism promoted by the ANC. The issue came to a head in 1979 when Buthelezi met with Oliver Tambo in London. Thereafter, Buthelezi severed all ties with the ANC. By the mid-1980s, Natal had become a killing ground with ongoing clashes between the IFP and organisations aligned to the ANC.

The Third

Force:

There was also mounting evidence of a mysterious ‘Third Force’ carrying out random attacks on commuters at taxi ranks and train stations. Hundreds of people were killed or injured in seemingly motiveless incidents. In some cases, isiZulu-speaking hostel dwellers were accused of the assaults, and this in turn led to the further running battles between ANC and IFP supporters on the township streets. The ANC believed that there were elements in the police and the security forces fueling the campaign of terror in order to destabilise the negotiations.

Double talk:

The ANC accused De Klerk of turning a blind eye to the violence because he preferred to negotiate with a ‘weak and dismembered ANC’ and to patch together a moderate alliance of parties of all races against the ANC. In the meantime, Buthelezi rejected all allegations that IFP supporters were instrumental in the violence.

The D.F. Malan

Accord:

Signed between the government and the ANC on 12 February 1991, an agreement was brokered on the meaning of the ‘suspension of armed action and related activities’. The Accord made political headway on issues of violence, but it had little impact on the ground.

Division:

Relations between the apartheid government and the ANC became increasingly strained as the violence continued unabated. Mandela held private talks with Buthelezi and signed codes of conduct, but bloodshed continued. The ANC was convinced that the government was behind the violence and that De Klerk’s failure to respond put negotiations in jeopardy.

In their own words

“My message to those of you involved in this battle of brother against brother is this: Take your guns, your knives and your pangas and throw them into the sea … We commend Inkatha for their demand over the years for the unbanning of the ANC and the release of political prisoners, as well as for their stand for refusing to participate in a negotiated settlement without the creation of a necessary climate … We recognise that in order to bring the war to an end, the two sides must talk.”

-Nelson Mandela, then Deputy President of the ANC, appeals to ANC supporters at a rally in Durban soon after his release in 1990

“Bull … It’s all bull … I am a Christian and all my life I have been committed to the precepts of Christianity.”

–Mangosuthu Buthelezi, then leader of the IFP, responding to allegations that the IFP were fueling the violence

“I think Gatsha Buthelezi is deliberately fanning the violence and his message to both De Klerk and Mandela is – give me recognition. If you exclude him from this process this is how it will go.”

-Allan Boesak, cleric and politician and anti-apartheid activist

“People see him [Buthelezi] as an obstacle … He demands to be feared, in the old fashioned way that Zulus are more than any other tribe … That’s nonsense. He believes that and he lets Zulus believe that. So he is actually dividing people in a big way.”

–Oupa Gqozo, then leader of the homeland of Ciskei

“De Klerk managed to persuade a significant community in SA and abroad that his hands were clean, that the violence was an inter-ethnic black on black fighting, that it was political rivalry between the ANC and IFP.”

-Chris Hani, speaking to business leaders about the violence, eight months before his assassination on 10 April 1993

“I don’t think that ethnicity is really the reason [for the violence], it’s a combination. The hostel dwellers who go out in search of people to kill live under dehumanising conditions and as such their whole approach to life is coloured by [this] … They don’t have their wives and children. They have nothing to lose.”

–Barbara Masekela, then member of the ANC’s National Executive Committee, the ANC’s Negotiations Commission and the ANC’s Women’s League

“We also had to deal with our own problematic people who just didn’t understand that the ANC could contribute to peace and harmony by stopping its own violence because our comrades were very violent. The self-defence units were being armed. There were comrades who were very short-sighted, who thought that you could defeat the enemy on the ground by outgunning them and we said, ‘You don’t have the means’.”

-Penuell Maduna, then member of the ANC’s Constitutional Committee

“I think the beginnings of that violence were very clear, that Buthelezi is a frightening megalomaniac. And Buthelezi believes that Natal and Zululand are his territory, and no organisation will be allowed there. So, while he talks of multi-party democracy when he’s in Washington, nobody has actually asked him how many parties are there in the KwaZulu Legislative Assembly.”

–Vincent Maphai, then Professor of Political Science

Explore the Archive

SABC Special Report on the IFP’s submission to the TRC regarding violence, September 1996.