Events around the release of political prisoners, Operation Vula and the Pretoria Minute

6 AUGUST 1990

Adil Bradow / Oryx Archives

Moving

forward:

After the historic meeting between the ANC and NP at Groote Schuur, a working group was set up to operationalise commitments and to ensure that the climate of violence and intimidation was resolved. A chief task of the group was to advise on ‘norms and mechanisms’ for dealing with the release of political prisoners, and also to draft a bill to grant indemnity for ‘political offences’ to the estimated 22 000 exiled ANC and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) cadres. In March 1990, prisoners on Robben Island went on a hunger-strike over the issue, unsure as to whether they would be granted indemnity or not. The Indemnity Act passed on 18 May 1990 granted temporary or permanent indemnity against prosecutions for exiles returning to South Africa.

Further obstacles:

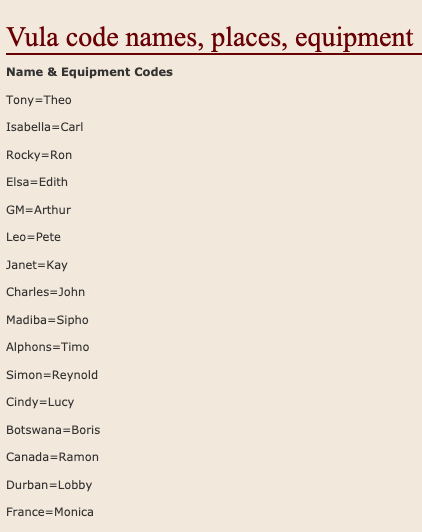

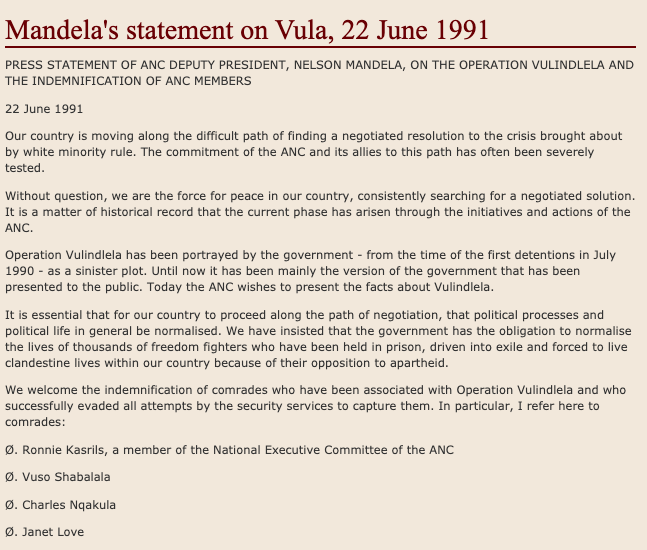

In general, progress was halting. On 25 July 1990, two weeks before the scheduled 6 August meeting between the ANC and the government to take negotiations forward, news broke of the arrest of 40 members of the ANC and SACP who were accused of being part of an ‘ANC plot’ code-named Operation Vulindlela, commonly known as Operation Vula, to overthrow the government by force.

Operation Vulindlela

(Open the Road):

As part of the underground struggle in the late 1980s, the ANC had launched this secret operation to step up and give direction to the ‘people’s war’ against the apartheid regime. The ANC infiltrated key operatives into South Africa, including Mac Maharaj and Siphiwe Nyanda in 1988, and Ronnie Kasrils in 1990. These ‘Vula operatives’ also developed secret means of communication between the still incarcerated Mandela and the ANC-in-exile. In the months that followed, Maharaj became Tambo’s eyes and ears inside South Africa.

After an intensive internal debate, the ANC decided to keep Operation Vula in place. It believed that it was ‘an insurance policy’ in case talks failed. Tambo was also concerned that the ANC should not allow negotiations to result in the movement being stripped of ‘our weapons of struggle’. Sanctions, the guerrilla force, and Operation Vula would remain until it was clear that the process was irreversible.

For the

government:

Vula confirmed De Klerk’s worst fears about secret plans to overthrow the government under the ‘pretence’ of negotiation and dialogue. Maharaj, Nyanda, Kasrils and six others were charged with ‘attempting to overthrow the government by force’. The NP demanded that the ANC abandon its policy of armed struggle. The ANC accused the government of failing to deal with the spiralling violence. This was a moment of intense crisis.

The Pretoria

Minute:

A breakthrough occurred on 6 August 1990. After a marathon 13-hour meeting, the ANC and the NP signed the Pretoria Minute in which the ANC agreed to suspend all armed actions ‘with immediate effect’. The government also made a number of key concessions: it committed to the release of political prisoners by September 1990; to starting the indemnity process by 1 October 1990; and to reviewing the lifting of the State of Emergency in Natal. A Joint Working Group was also formed to attempt to move the process of releasing political prisoners forward. These concessions were described as a ‘historic truce’ that allowed the two main parties to overcome their divide and clear the obstacles to negotiations.

“In the interest of moving as speedily as possible towards a negotiated peaceful political settlement … The ANC announced that it was now suspending all armed actions with immediate effect. As a result of this, no further armed actions and related activities by the ANC and its military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, will take place.”

-The Pretoria Minute, 1991

“We are convinced that what we have agreed upon today can become a milestone on the road to true peace and prosperity for our country … The way is now open to proceed towards negotiations on a new constitution. Exploratory talks in this regard will be held before the next meeting which will be held soon.”

– The Pretoria Minute, 1991

Responses to the

Pretoria Minute:

The PAC and Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO) recorded their unequivocal rejection of this agreement. There was also a considerable amount of disquiet within ANC ranks, especially from its youth and a number of people in the ANC who bitterly opposed the suspension of the armed struggle. At the ANC Conference in December 1990, ANC delegates vented their anger at the moderation shown by the ANC. The Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and its leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, welcomed the Pretoria Minute. However, he threatened that the violence would not end until there was agreement between himself and Mandela. It seemed that the IFP leader felt slighted by the fact that he was not invited to these meetings, a theme that would surface throughout the negotiation process.

In their own words

“Operation Vula was a mission inspired by this desire to bring decision-making closer to the people who were at the coal face of the struggle – the struggling masses, the underground structures of the ANC as well as Umkhonto we Sizwe itself, the underground fighters.”

-Siphiwe Nyanda, then member of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), and member of Operation Vula

“We wanted to achieve an armed victory … but not at the cost of our country lying in ruins … We were mindful of the fact that many struggles before us had reached a point in their prosecution where there had to be talks, negotiations, cease fire.”

–Siphiwe Nyanda, then member of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), and member of Operation Vula

“We couldn’t trust them … We could not, at that stage, believe that what was being started would have some kind of permanence. Operation Vula was on standby and if anything went wrong we would have, of course, called upon our combat units to then move in terms of the programme that had been defined.”

-Charles Nqakula, then member of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), and commander of Operation Vula

“Joe Slovo came to me privately with a proposition. He suggested we voluntarily suspend the armed struggle in order to create the right climate to move the negotiation process forward … My first reaction was negative. I did not think the time was ripe. But the more I thought about it, the more I realised that we had to take the initiative and this was the best way to do it. I also recognised that Joe, whose credentials as a radical were above dispute, was precisely the right person to make the proposal [to the National Executive Committee].”

–Nelson Mandela, then Deputy President of the ANC, reflecting in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom

“The government has all the powers in their own hands – parliament, the administration, the police. We have got the people. We have suspended armed struggle, which is an important contribution to the process, but we are not going to immobilise our people. That’s the source of our strength. We shall continue to engage in mass action.”

–Chris Hani, then senior leader of the SACP and then chief of staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the ANC

“On the one side we have to develop a process of mutual understanding towards negotiations. At the same time, we have to remember that we will most likely be opponents once we get to the negotiating table because of our different political ideologies.”

-Roelf Meyer, then Deputy Minister of Constitutional Development and NP negotiator