Events leading up to the signing of the National Peace Accord and the establishment of the Patriotic Front

14 SEPTEMBER 1991

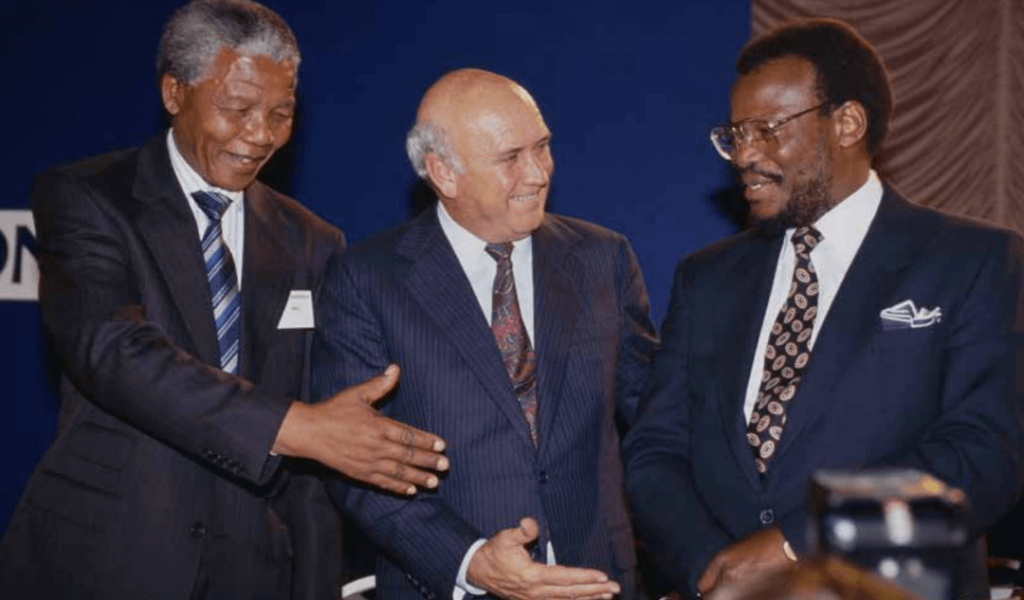

President of the ANC Nelson Mandela (L), President Frederik Willem de Klerk and the Inkatha Freedom party leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

April-May 1991:

Business and church facilitators got together and offered their services to the political process to put an end to the violence. On 22 June 1991, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and business leader, John Hall, co-chaired a preparatory meeting for a peace summit. This was the first time that the ANC, the NP, and the IFP had sat around the same table to discuss the issue of violence. There was also a wide range of other parties and unions. All agreed to set up a Preparatory Committee to oversee the negotiation of peace agreements, to be signed at a future peace conference which would aim to be even more comprehensive.

August 1991:

Two months after the preparatory meeting for a peace summit, the Consultative Business Movement (CBM), an organisation representing a section of church and business leaders led the “National Peace Initiative” for further talks. Several drafts of a National Peace Accord were written. The Accord was finally agreed at noon on Friday 13 September 1991.

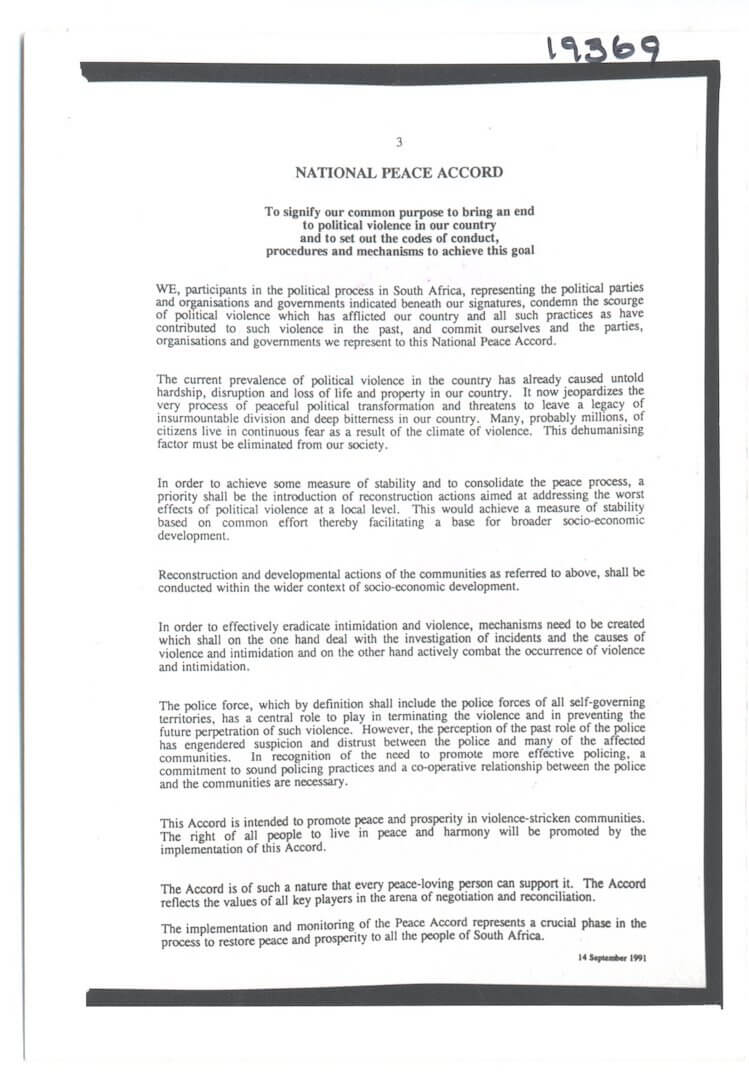

14 September 1991:

The mood was buoyant when 24 political groupings signed the National Peace Accord at the Carlton Hotel, sealing their commitment to end the violence. The Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and Azanian People’s Organisation (AZAPO) supported the spirit of the Accord, but refused to be part of any structure which included the government. They were also not convinced that liberation armies should be laying down their weapons at this moment. On the right, the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), the Conservative Party, governments of ‘independent’ homelands of Bophuthatswana, Transkei and Venda also did not sign. Despite this, a multilateral process had laid the foundation for future talks going forward.

The National

Peace Accord (NPA):

The NPA aimed to end violence by setting up national, regional, and local peace committees and special criminal courts. It laid out limitations to the activities of the security forces and police, and compelled them to protect all people from criminal acts. The Accord also sought to establish a multi-party democracy, assist in economic redevelopment, and ensure peaceful power-sharing. The peace structures went on to manage events and marches; there were forums for discussion before events in order to plan where the monitors would be with radios, etc. ensuring that violence would not erupt.

Community

policing:

The National Peace Committee met for the first time on 20 September, and from that flowed all the other peace structures. The NPA provided the South African Police (SAP) with its first community policing experience. Up until the signing of the NPA and the setting up of peace structures, the SAP had no experience with police-community relations.

The peace

doves:

The advertising agency, Hunt Lascaris, was commissioned to design an emblem for the peace process. It created a logo with two overlapping doves carrying an olive branch, which appeared on t-shirts, posters, and billboards. This became an iconic symbol of peace during the negotiations.

Consequences:

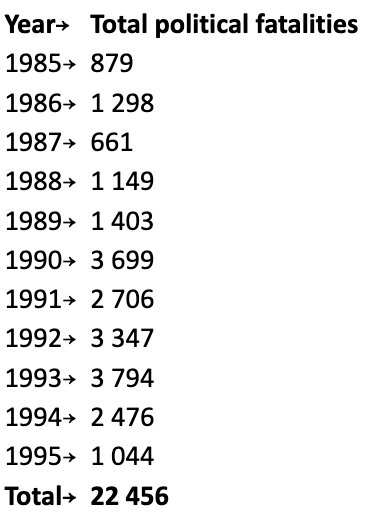

The peace structures through the length and breadth of South Africa brought people together in the communities, and often preempted further violence. They also brought tens of thousands of people of most diverse backgrounds into a national participatory process of safeguarding the endeavours being made during negotiations. Violence, however, continued to be one of the greatest threats to the success of the negotiations.

The Patriotic

Front (PF):

The signing of the Accord was followed by the launch of the PF, a loose alliance of some 92 organisations that had opposed apartheid. At its inaugural conference, the PF issued a declaration that included three important principles for the negotiated transfer of power: 1) an interim government had to oversee the process of democratising South Africa as the present government lacked legitimacy; 2) only a constitutional assembly, elected on a one-person one-vote basis in a united South Africa, could draft and adopt a democratic constitution; and 3) an all-party congress should be held as soon as possible.

The way

forward:

Although there was little doubt that the ANC and the NP were the two major contenders for power in the country, the ANC strongly believed that the negotiations would not work if a deal was simply hammered out between the two. Weeks of hard bargaining in bilateral and multilateral meetings followed. Suspicions between the parties remained rife. The more hard-line faction in the NP believed that the ANC was in the thrall of both the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and that these organisations were still hoping for ‘a radical seizure of power’.

In their own words

“Without peace there can be no democracy, and it is equally true that without democracy peace remains under constant threat.”

-Joe Slovo, then SACP representative in the ANC negotiations team

“The ethos of the transition, its proceeding by consensus and its thrust towards understanding and reconciliation, was first endorsed and embodied in the National Peace Accord.”

–Liz Carmichael, then church representative in the Alexandra Peace Committee

“The objective of the National Peace Accord was really to try and stop all or limit the killing of innocent people; and secondly to create enough stability for the negotiations to start and to proceed because unless we could get through those negotiations, there was no hope of getting to the other end and to democratic rule for the rest of the country.”

-Peter Harris, then National Coordinator of the NPA

“We set up four working groups – one to do a code of conduct for political parties, one to do a code of conduct for the police and the South African Defence Force, one which was looking at peace committees and the institutional structures, and one to deal with socioeconomic transformation, and from that we achieved and produced the Peace Accord.”

–Jayendra Naidoo, then member of the National Peace Secretariat

“The Peace Accord provided the best possible chance to find ways to stop the violence. Also, up to that stage we had not negotiated; we had simply talked. The Peace Conference offered a learning opportunity which came in handy in the negotiations which

were to follow.”

-Roelf Meyer, then Deputy Minister of Constitutional Affairs and NP negotiator

“Peace workers say that … If they had the resources, they could do up to three times more than now. They are hamstrung because the government has not allocated sufficient resources, and the private sector has not yet seen its way clear to do so. I believe the peace structures could still be one of the vehicles that turn the tide

of violence.”

–Cyril Ramaphosa, then Secretary-General of ANC

“This is the beginning of the establishment of democratic power – three years ago none of us thought that the police of South Africa would ever

be accountable.”

-Barbara Masekela, then member of the ANC National Executive Committee, the ANC’s Negotiations Commission and the ANC’s Women’s League

“Without the Peace Accord we would be far worse off … People supported it in the sense that the various political leaders signed it so one could always shove the paper under their noses and say, ‘But you signed it.’”

–Sheila Camerer, then Deputy Minister of Justice and NP negotiator

“The whole idea of a take-over still isn’t dead in the ranks of the ANC. I have my doubts whether the ANC as an organisation isn’t merely seen by the communists as a vehicle to get there.”

-Tertius Delport, then a central negotiator for the NP