Signed

Into Law

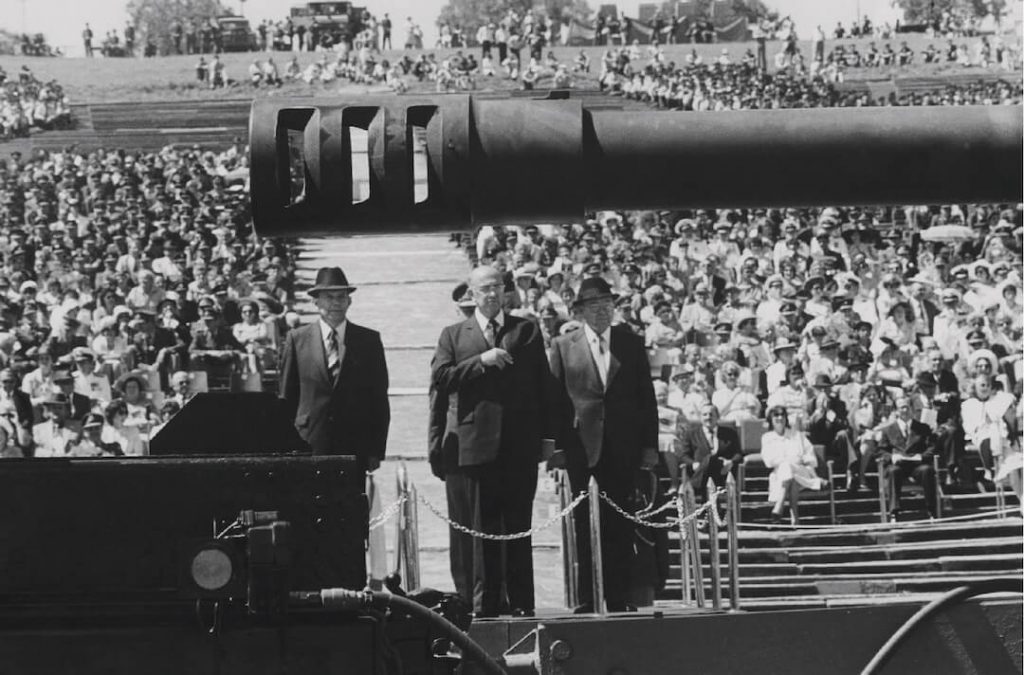

Finally, the Constitution was ready to be signed. The place chosen for the ceremony was Sharpeville, the township outside the previously all-white town of Vereeniging. It was here that the Boers and British had signed the peace treaty that ended the South African War and effectively disenfranchised the black majority. Fifty-eight years later, on 21 March 1960, it was the same place where the police killed 69 people who were peacefully protesting against the pass laws outside the police station in Sharpeville. This event was a turning point in the history of South Africa. The government introduced even more draconian security legislation. The ANC took the decision to embark on armed struggle. The date chosen for the signing of the Constitution was 10 December 1996, 6 days after its historical certification by the Constitutional Court.

Navigate this section

Signing the Constitution

When Nelson Mandela, after years of negotiation, had to sign the Constitution in 1996 … not only did it have to be in Vereeniging, but specifically in Sharpeville in Vereeniging, because those who sacrificed must know that their struggle was not in vain and their efforts had not been forgotten.

I was not surprised when 10 December was suggested as the date for the signing ceremony. It was, after all, International Human Rights Day when in 1948 the Universal Declaration had been accepted by the General Assembly of the United Nations.

Leon Wessels

then Deputy Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

It was not in an air-conditioned office. It was not in a boardroom and it was not in some secret location that we did the signing. It was in a stadium, a very public place. It was an enactment of what our struggle has been all about – a very public event.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

Today, together as South Africans from all walks of life and from virtually every school of political thought, we reclaim the unity that the Vereeniging of nine decades ago sought to deny.

Nelson Mandela

Then President of South Africa

Here, at Sharpeville, in Vereeniging, both powerful symbols of past relationships between South Africans, we are making a break with the past. A break with the pain, a break with betrayal. We are starting a new chapter.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

Because the physical constitutional text was final and needed to stand the test of time, we procured special paper on which to print it that would not yellow with age. Three copies were printed, two of which were beautifully bound and covered.

Hassen Ebrahim

then Executive Director of the Constitutional Assembly

I have one last task to perform as Chairperson of the Constitutional Assembly. Mr. President, it is my honour and privilege to present to you the Constitution for your signature. I call on all of you here today – and all South Africans watching at home – to bear witness. May this moment be remembered as a milestone in the struggle for a just and free South Africa.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

No sooner had President Mandela put down his pen when a beaming Ramaphosa spontaneously hoisted the Constitution up for the enthusiastic

crowd to applaud.

Today marks the end of an era, and the beginning of a new one. It’s the end of two years of work by the Constitutional Assembly, and the end of a much longer phase of negotiation and transition. But, more than that, it’s the end of a 350-year struggle for national unity, for real ‘Vereeniging’ between our people as South Africans.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

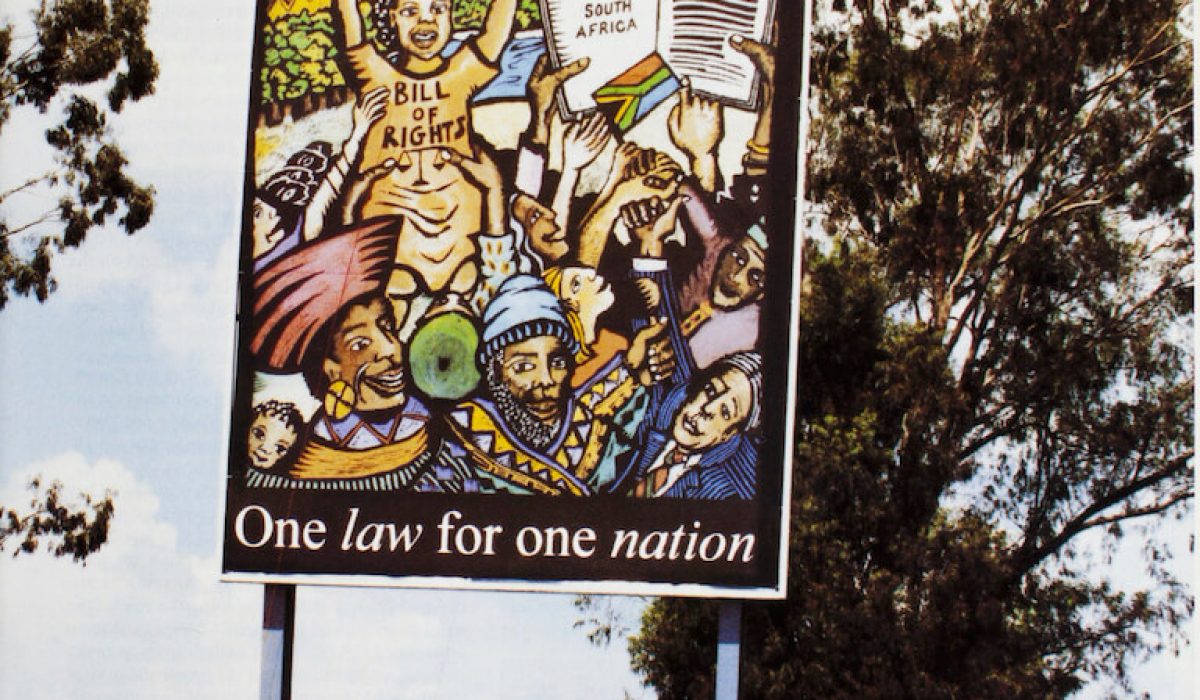

Finally, there was one law for one nation. The Constitution came into effect on 4 February 1997, replacing and repealing the Interim Constitution of 1993.

Whilst watching Madiba sign the Constitution, there were a lot of emotions that went through my head. I was humbled that I was watching history unfolding. I was saying to myself, this is what it has all been about. The 77 people that died here, and hundreds of thousands of other people who died throughout the country, they all died to make sure that we have this document. This is the document that should wipe away the tears and the blood that was shed here. This document is an attempt to correct

that horrible history.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

I lifted the Constitution into the air in the heat of that moment. I hadn’t planned it. I had to do that to show the people that this is it. This is the document that you struggled for, that you fought for that you died and wept for, this is it. This is the Constitution that binds us all together. Leon Wessels was standing right there. This document binds us together to a common destiny, a common future and a joint aspiration of what this country could be.

It was magic.

Cyril Ramaphosa

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

De Klerk was not on the stage nor was he asked to make a speech. I felt for him. As leader of the opposition, he was sitting in the sun and following the proceedings as a spectator. Vereeniging was his old constituency and his old political stronghold. He had played an enormous role in the transition and would have made a fitting speech. But by walking out of the Government of National Unity, he relinquished the office of deputy State President and made it easy for his opponents to relegate him to this spectator’s role.

Leon Wessels

then Deputy Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

The signing ceremony was the highlight of my political career. My participation – sitting next to Mandela and Ramaphosa and saying the final word of thanks – was my last political function.

The day was filled with emotion. My father had been a policeman in Vereeniging, transferred there shortly after the heartbreaking catastrophe happened at Sharpeville. I often accompanied him there when he visited the local police stations. I remember how afraid I was when we moved around after dark; wondering whether my father was brave or did he know the lay of the land? Years later, I was back in Sharpeville to celebrate the dawn of a new South Africa.

Leon Wessels

then Deputy Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

Our Constitution gives us ample elbow room to develop into what we want to be. It’s up to us. No one is going to do it for us. No avatar will descend from high. We need good leadership. We need great vision. Our people want to know where this country is going. So we need the leadership to begin to say, ‘this is our lodestar, this is where we are going.

Penuell Maduna

then ANC member of Parliament

Friends and compatriots; By our presence here today, we solemnly honour the pledge we made to ourselves and to the world, that South Africa shall redeem herself and thereby widen the frontiers of human freedom. As we close a chapter of exclusion and a chapter of heroic struggle, we reaffirm our determination to build a society of which each of us can be proud, as South Africans, as Africans, and as citizens of the world.

As your first democratically elected President I feel honoured and humbled by the responsibility of signing into law a text that embodies our nation’s highest aspirations. In writing the words which today become South Africa’s fundamental law, our elected representatives have faithfully heard the voice of the people. Now, at last, they are embodied in the highest law of our rainbow nation.

Today, together as South Africans from all walks of life and from virtually every school of political thought, we reclaim the unity that the Vereeniging of nine decades ago sought to deny.

We give life to our nation’s prayer for freedom regained and continent reborn;

God bless South Africa; Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika; Morena boloka sechaba sa heso; God seen Suid-Afrika.

Extracts from President Mandela’s speech at Sharpeville

10 December 1996

Reflections by the drafters and others

A few months after the Constitutional Assembly had adopted the Constitution, negotiators had time to sit back and reflect on what they had achieved. What did they think about the Constitution?

I don’t think it is flawless. I don’t think it is without any mistakes. Given the time that we had to draft and finalise the Constitution, I think we did very, very well.

Cyril Ramaphosa

Then chair of the constitutional assembly

This document was more than a Constitution. It really was a settlement that brought South Africa together for the first time. We could really say, ‘Now we have one common law that unites us.’ The possibility of not supporting the Constitution

never came to my mind.

Roelf Meyer

then NP member of the Constitutional Assembly

There are very creative things that are there that are unusual. The extent to which we are protecting gay rights, our approach to socio-economic rights and the question of the application of the Bill of Rights – that it’s not just the question of the relationship between the state and the individual, but also it governs relationships amongst individuals. Of course it’s

not an ANC Constitution.

Blade Nzimande

then ANC member of the Constitutional Assembly

We would have liked the Constitution to go further in the question of expanding provincial powers, but other than that, on the governance side, it’s done extraordinarily well. I have been in opposition politics all my life and you don’t get many opportunities to be creative.

Colin Eglin

then DP member of the Constitutional Assembly

We South Africans did it ourselves. We created a unique process that ensured maximum input of our people from all walks of life. A sense of common citizenship began to emerge through the give and take of debate. The result of the inclusive way of doing things, listening to many voices, was a remarkably forward-looking document that received nearly 90% approval in Parliament. Our Constitution was the product of struggle, intelligence and inclusion. Its success in action will depend upon these very same qualities.

Justice Albie Sachs

The measure of our success was that the process was conducted in a manner that gave the text itself the legitimacy it needed. This became part of the South African miracle, which was made possible only because of sheer determination. We captured the imagination of the people in South Africa and the

respect of the world.

Hassen Ebrahim

then Executive Director of the Constitutional Assembly

What lessons were learned?

We learnt three lessons. Firstly, we learned that, first and foremost, it was important never to let go of your dream. The participants ought to believe that a solution is possible and obstacles can be overcome … Secondly, we realised that you cannot beat your negotiating partner into submission. You must have the maturity to compromise. Thirdly, we also learned that one should be open at all times and give our constituencies as

much information as possible.

Leon Wessels

then Chair of the Constitutional Assembly

The Democratic Party was dubbed the ‘1.7% Party’. In terms of the number of votes we had no power. I think That’s where the skill of negotiating comes in. I had a very simple rule. If you wanted anything in the Constitution, you had to sell it to the ANC. If you wanted anything out of the Constitution, you had to persuade the Nats (National Party) to block it. At times, you had to go to the media, let them bat on a particular issue. You always had to ask, ‘In addition to charm and intellectual arguments, how can you have more clout?’

Colin Eglin

then DP member of the Constitutional Assembly

There were many frustrations:

It can be terribly frustrating and very tiring and extremely boring at times, but I do enjoy the cut and thrust of it, the process of trying to find solutions. It is a real intellectual challenge. So I think while you’re in it you often get very frustrated and tired and upset even, but I think when you take a more bird’s-eye view, you have a much greater sense of achievement.

Willie Hofmeyr

then ANC member of the Constitutional Assembly

What were the highlights of the process?

I think the real jewel in the crown is our Bill of Rights. We put affirmative action as a constitutional principle in a Bill of Rights to provide redress for the past. We have economic and social rights in the Constitution, thus resolving the silly debate that the only traditional political rights can be legally protected. We have provisions which are unique, like the right to information as a constitutionally protected right.

Kader Asmal

then ANC member of the Constitutional Assembly

It was not easy for me as an African woman to make my own voice heard on behalf of the women who could never come and speak here, so one had to really make the best of it and I really regard myself as having been honoured and very lucky to participate in it.

Baleka Mabete-Kgositsile

then ANC member of the Constitutional Assembly

I am personally very glad that I had the opportunity to spend my attention full-time on the constitution-making exercise from the National Party’s point of view. One feels that you almost didn’t exist during that period, but it was all worth it. Personally, if I look back, I think that was the only way to do it. We could have drawn it out for longer and we would not have achieved a better result, I’m quite sure.

Roelf Meyer

then NP member of the Constitutional Assembly

South Africa’s Previous Three Constitutions

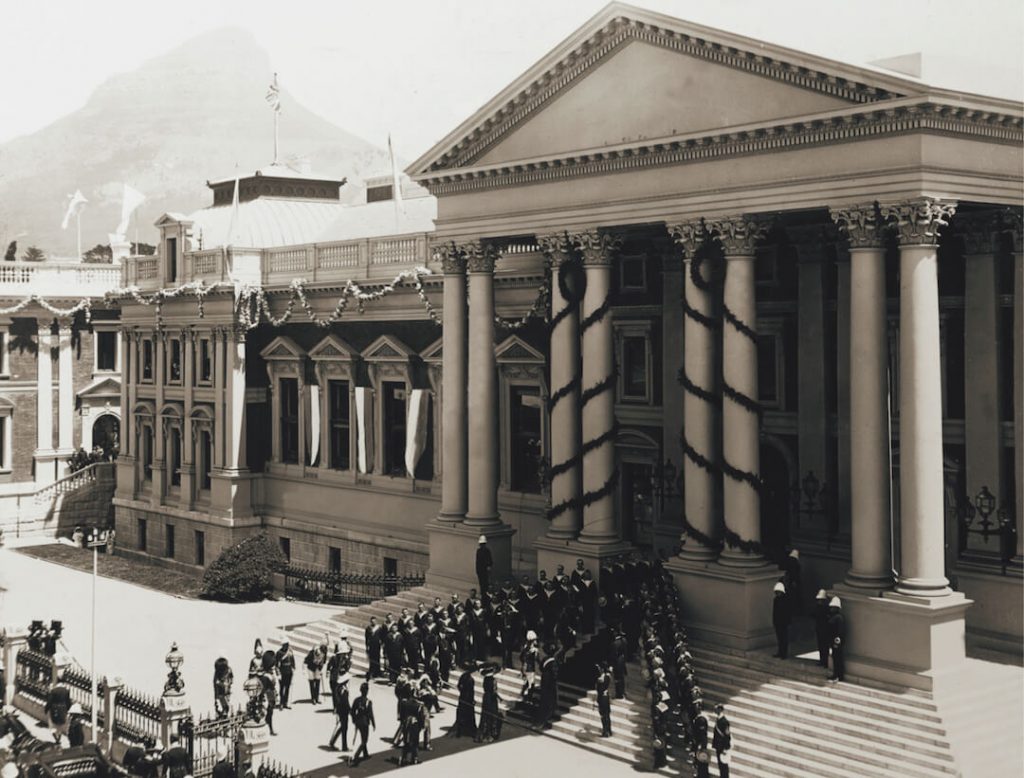

South Africa’s First Constitution

1910

The Treaty of Vereeniging, signed by the British government and the two Boer Republics in 1902, officially ended the bitter and protracted South African War. The two Boer Republics agreed to come under British sovereignty, with the promise of eventual self-government. For the former enemies this was an important if tenuous effort at reconciliation. But for black people, many of whom had fought in the war and were excluded from the peace settlement, this was just the beginning of the political disempowerment they would endure for the most part of the twentieth century.

South Africa’s Second Constitution

1961

Verwoerd’s dream was to turn South Africa into a Republic ruled by the Afrikaner and free from British interference. This would allow the South African government to deal with its ’native problem’ in whatever way it chose, without reference to the British Crown. An all-white referendum held on 5 October 1960 indicated that 52 percent of white citizens were in favour of a Republic. With this mandate, Verwoerd passed legislation to turn the Union into the Republic of South Africa. Having made this constitutional change, Verwoerd was obliged to request from fellow members of the British Commonwealth that South Africa remain a member.

South Africa’s Third Constitution

1983

In 1980, Prime Minister PW Botha revisited the findings of the Theron Commission, which had been appointed by his predecessor BJ Vorster to look into a new constitutional arrangement for the coloured people of South Africa. These findings became the basis for the 1983 constitution.

The graphics used in this component are drawn from the following sources:

Constitutional Assembly Publication, You and the Constitution, 1995

Constitutional Assembly Publication, Constitutional Talk, Volume 9, 1995

The quotes used in this component are drawn from the following sources:

Constitutional Assembly Annual Report, May 1994 – May 1995

Christina Murray, A Constitutional Beginning: Making South Africa’s Final Constitution, 23 U. Ark. Little Rock L. Rev. 809 (2001). Available at: http://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol23/iss3

Mike Nicol, The Making of the Constitution

Parliament of the Republic of South Africa (2018) Theme Committee Book Series 1-6