Speaking Truth to Power

Minister of Health and Others v Treatment Action Campaign and Others (2002)

What is the role of the Constitutional Court in saving babies from contracting HIV/AIDS?

Can the Constitutional Court order the government to change its policy, especially when millions of lives are at stake?

Background

When President Mbeki assumed the presidency in May 1999, the death toll as a result of the AIDS epidemic was frightening. In that year alone, around one quarter of a million people died in South Africa of AIDS-related causes. The President had publicly expressed the view that HIV did not cause AIDS. The Minister of Health had given support to that approach and vision. There were intense feelings in the country around the issue, and a sense that all the promises of a new democracy were being robbed.

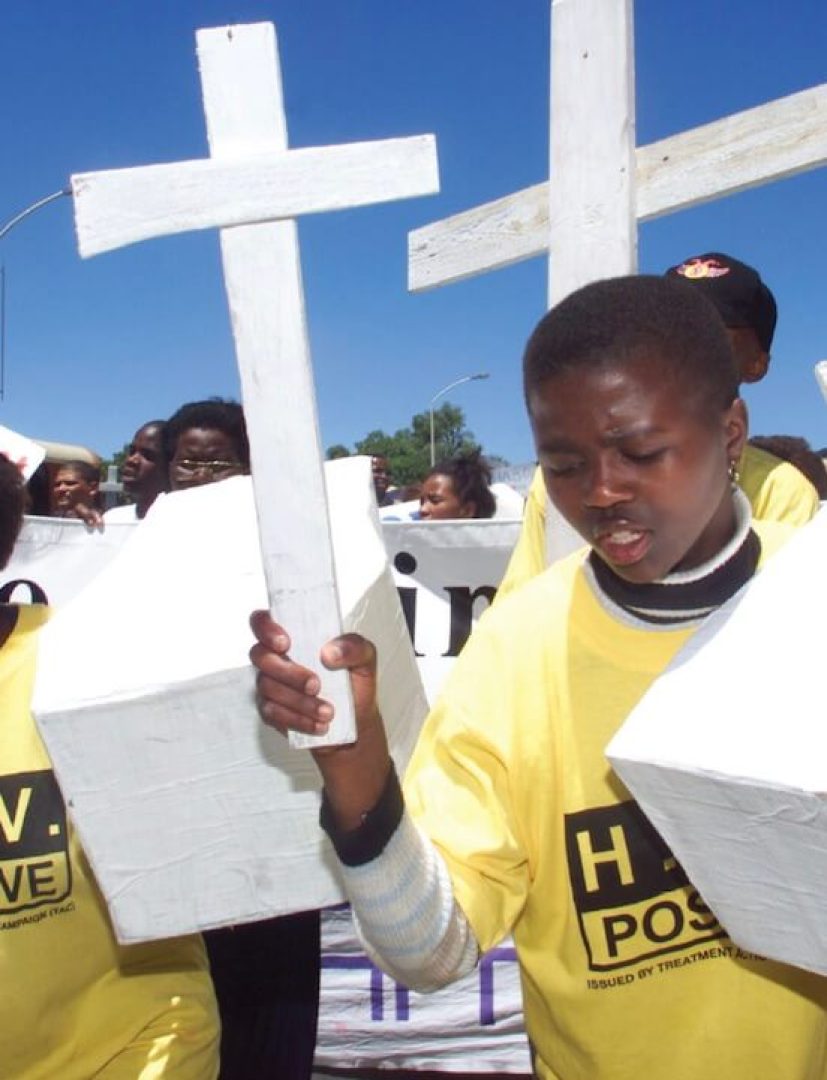

The Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), founded to tackle the iniquities of drug pricing, was forced to turn its attention to the government’s response to the HIV/Aids crisis instead. It did so, by turning to the courts. The TAC sought an order requiring President Mbeki’s government to make a drug, Nevirapine, available that enabled pregnant mothers to halve the risk of transmitting HIV to their babies.

While the government had developed a programme for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV, they had limited access to Nevirapine to two test sites in each province. The manufacturers of Nevirapine had offered to provide the drug free of charge for five years, but the government refused to extend the programme to include all public health facilities.

The current situation, in which women with HIV are unable to take appropriate measures to protect their health and that of their infants, has a devastating impact on their lives. That situation is avoidable.

Siphokazi Mthathi

TAC member, 2002

If you were poor, black and had HIV, you died because you couldn’t afford the medicine. It was the policy of the government not to provide the medicines. There was a point where 800 to 1 000 people were dying daily of HIV. It seemed inconceivable …

Mark Heywood

Leader of the TAC, 2016

Path to the Constitutional Court

The TAC challenged the government’s restriction of Nevirapine in the High Court. The High Court rejected the government’s assertion that Nevirapine was toxic and would cause long-term resistance for women. The High Court concluded that the government’s policy in “prohibiting the use of Nevirapine outside the pilot sites in the public health sector [was] not reasonable and that it [was] an unjustifiable barrier to the progressive realisation of the right to healthcare”.

The High Court ordered that the government “plan an effective comprehensive national programme to prevent or reduce mother-to-child transmission for HIV”. The government was also ordered to lodge its details and progress of the programme with the court. The government took this matter on appeal to the Constitutional Court.

Some of the Arguments

Minister of Health

The Ministry of Health government highlighted its concerns regarding the safety and efficacy of Nevirapine requiring continuation of the government’s research programme. It contended that it was restricting Nevirapine to the pilot sites to gain experience in administering it. An important reason for this decision was that the government wanted to develop and monitor its human and material resources nationwide for the delivery of a comprehensive package of testing and counselling, dispensing of Nevirapine, and follow-up services to pregnant women attending public health institutions.

Treatment Action Campaign

The TAC argued that the government’s policy on HIV/Aids was irrational. They said that it was not reasonable to restrict access of Nevirapine to the test sites. Nevirapine had been found to be safe, and if administered to the mother and baby just before and after birth, it would radically reduce the transmission of HIV.

What did the Constitutional Court decide?

In a unanimous judgment, the Court ordered the government to make Nevirapine, or a suitable substitute, available at public clinics to pregnant mothers who sought it. The Court stated that to deny newborns outside the test sites a potentially life-saving drug was inconsistent with section 27 of the Constitution – the right to healthcare. The Court concluded that an extensive and inclusive antiretroviral (ARV) treatment programme was a realistic and reasonable demand on the government and the public health system. This judgment also had implications for the principle of separation of powers. During the court battle, the government argued that the High Court’s order infringed the doctrine of separation of powers and had impeded on its policy-making powers. The Constitutional Court addressed this tension by stating that courts are ill-suited to adjudicate upon issues where court orders could have multiple social and economic consequences for the community. However, the Constitution contemplates rather a restrained and focused role for the courts, namely to require the state to take measures to meet its constitutional obligations. The Court found that the government had not fulfilled its obligation in this case.

Impact and Significance

Prior to the judgment, an HIV positive pregnant mother had a 30% chance of giving birth to a baby with HIV. There were 75 000 deaths a year in 2000/2001 of infants with HIV.

The judgment was a resounding victory in the fight for universal access to treatment, as well as for rational public discourse on HIV/AIDS. As a simple matter of history, it was the judgment that eventually forced the government to take decisive action to stem the tide of the epidemic.

Today, nearly 1.5 million people in South Africa are on ARV treatment. It is the largest publicly provided AIDS treatment programme in the world. This is undoubtedly the most significant material consequence of the decision.

I gave birth to an HIV positive baby who should have been saved. That was my experience, the sad one, and I will live with it until my last day.

Busisiwe Maqungo

activist, 2002

We as the TAC used our constitutional rights to protest. We used our right to access healthcare services – section 27. We insisted on our right to equality – section 9 and our right to participate in political processes … Over four to five years ordinary people dying of aids joined this organisation and exerted pressure on the government to fulfil its constitutional responsibilities. We eventually went to the Constitutional Court.

Mark Heywood

former leader of TAC, April 2019

This case was constitutional democracy functioning at its best … The applicants were of one mind. Their message to the Court was clear – ‘We are not pariahs. We have a disease and we are entitled in terms of the Constitution to have our humanity respected and our need for medical care attended to by the state within its capacity’.

Justice Johann Kriegler

4 April 2002

In terms of impact, the two cases heard by the Constitutional Court that stand out markedly in terms of their ultimate impact are TAC and Nkandla (Economic Freedom Fighters v President of the Republic of South Africa). The TAC proves how important socio-economic rights can be.

Justice Albie Sachs

2019

Since the judgment, every mother who lives with HIV has access to the drugs that prevent her from transmitting the virus to the baby. Today, less than 2 000 children are born with HIV, and even fewer die because of it.

The TAC continues to represent users of the public healthcare system in South Africa, and to campaign and litigate on critical issues related to the quality of and access to healthcare.