The Struggle for LGBTQIA+ Rights

South Africa’s post-apartheid constitutions – the 1993 Interim Constitution and the 1996 Constitution – were the first in the world to include an explicit prohibition of discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation. The inclusion of such provisions led to broad judicial and legislative protection for LGBTQIA+ rights, from the decriminalisation of sexual behaviour to marriage equality. This timeline plots significant moments in the struggle for freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation.

The gay pride flag of South Africa, designed by Eugene Brockman, is a hybrid of the LGBT rainbow flag and the new South African national flag which was launched in 1994 after the end of apartheid. The flag is a gay pride symbol that aims to reflect the freedom and diversity of the South African nation and build pride in being an LGBT South African.

Pre-colonial societies

First People’s labelling of relationships and prohibition

South Africa’s First People, the Khoisan, as well as early African societies, had terminology referring to alternative sexual practices and gender expressions. The Khoisan term Koetsire referred to men who were sexually receptive to other men, while the word soregus was used to describe a friendship that involved same-sex masturbation. The words inkotshane in IsiZulu, oukonchana in Sesotho, tinkonkana in Mpondo, and nkhonsthana in Tsonga all expressed sanctioned practices that were not seen in opposition to heterosexual identities but rather in addition to them. Sexual, gendered identities and same-sex practices were also depicted in rock art.

1650 -1803

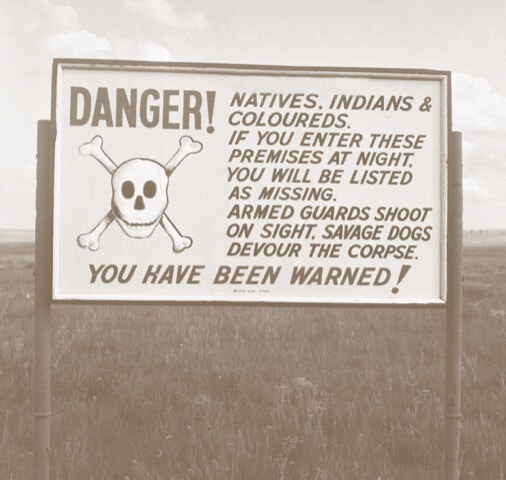

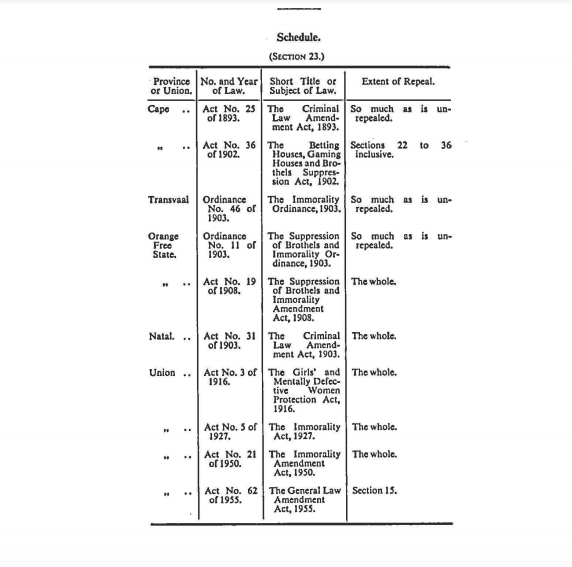

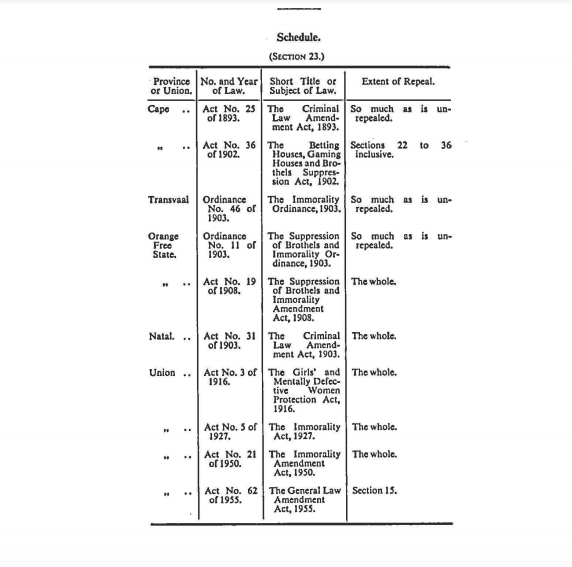

The first laws against freedom of sexual expression

When Dutch settlers occupied the Cape, they adopted Roman-Dutch Law which made sodomy a common law offence that could lead to death by hanging as a punishment. Inter-racial relationships were also prohibited. Following the British occupation of the Cape in 1803, homosexual acts remained criminalised, and legal persecution of individuals who engaged in same-sex intimacy continued. Sodomy remained an offence in South Africa until 1998.

1907

The Taberer Report branded same-sex relations as ‘loathsome’

Henry Taberer, a member of the Native Affairs Department, compiled a report demonstrating evidence of same-sex relationships among males working in the gold mines which he described as ‘loathsome’ and ‘disgusting’. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, apartheid leaders turned a blind eye believing that homosexuality on the mines discouraged men from seeking sexual congress in surrounding towns and ensured a consistently productive workforce. The government stated that same-sex relationships were “a necessary evil in order to ... contain the threat of unbridled black male sexuality.”

1948

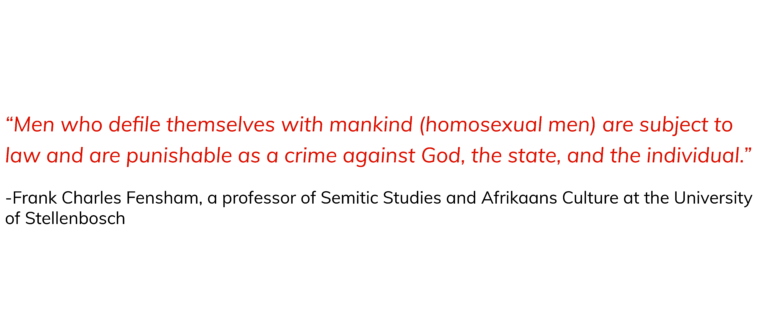

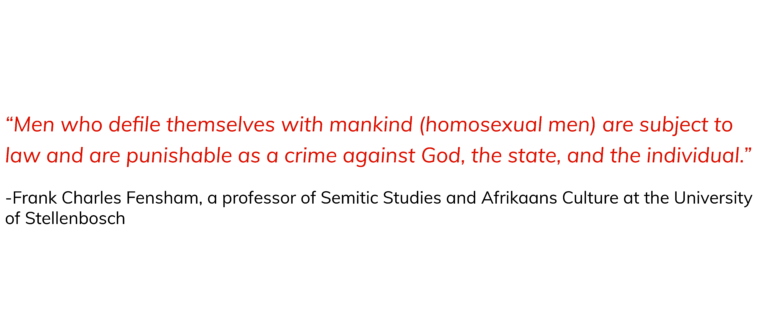

In the name of Christianity

The apartheid government justified apartheid in terms of a Christian doctrine and instituted many laws to support their form of Christianity. One such example was the programme of Christian national education that was developed in the schools. It was also within this ‘religious’ framework that the government stepped up its enforcement of its conservative and repressive attitude towards same-sex relationships. From 1948 onwards, an increasingly stringent set of anti-sodomy laws enforced by the police led to the increasing persecution of the gay community.

1949

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act

Parliament passed the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act 55 of 1949, building on the 1927 Act of the same name.

This act prohibited marriage and any form of cohabitation between white and black people and also prohibited ‘unnatural’ sexual acts between males. It was to be amended several more times to curb same-sex relationships. This act, together with the Immorality Act, as well as the common law taken over from the Netherlands and England, was used to criminalise sodomy.

1950 - 1960s

Sexual identities and visible ‘moffie’ subcultures

Despite sexual intimacy between two men being a crime, a gay subculture flourished and became increasingly visible in publications such as Drum and Golden City Post. The ‘moffie subculture’ in Cape Town along with the annual Cape Carnival received particular attention.

“It was the most astonishing party you have ever seen … there was whispering in corners, and smudged lipstick and high-pitched giggles. But there were no women … This was a party given by Cape Town’s famous ‘moffies’ … There were rouged pugilist faces peeping from underneath ginger wigs. And sometimes the shoulders above the strapless evening dresses had muscles that would have done credit to a weightlifter.”

-Drum magazine in an anonymous account of a party held in January 1959

1956

35 men arrested for ‘indecent assault’

Police arrested 35 men for ‘indecent assault’ on the Durban Esplanade - a waterfront area where homosexual men had been meeting since World War II. Some scholars argue that this arrest contributed to the inclusion of homosexual conduct in the 1957 Immorality Act.

1962

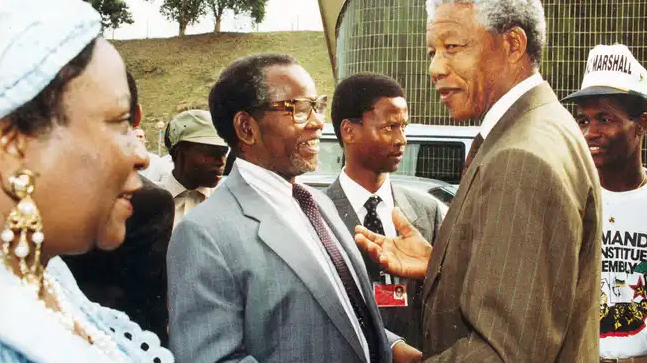

Cecil William’s courageous contribution to help Mandela

Cecil Williams, the British-born son of a blacksmith who immigrated to South Africa, was a popular and debonair figure in the anti-apartheid resistance movement. He was open about his gay identity despite the constant threat of persecution. During WW2, he joined the navy and fought against Hitler. After the war, he joined the Springbok Legion - a group of ex-servicemen and women who were now determined to fight racism in their own country. He was later imprisoned for his activities in the banned South African Communist Party. He became involved in the underground work of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) and played a key role in aiding Nelson Mandela when he was on the run from the police in the early 1960s. In order to enable Mandela to carry on his underground activism and avoid detection, Mandela disguised himself as William’s chauffeur. It was in this guise as David Motsamayi that Mandela was ultimately arrested near Pietermaritzburg in 1962.

1966

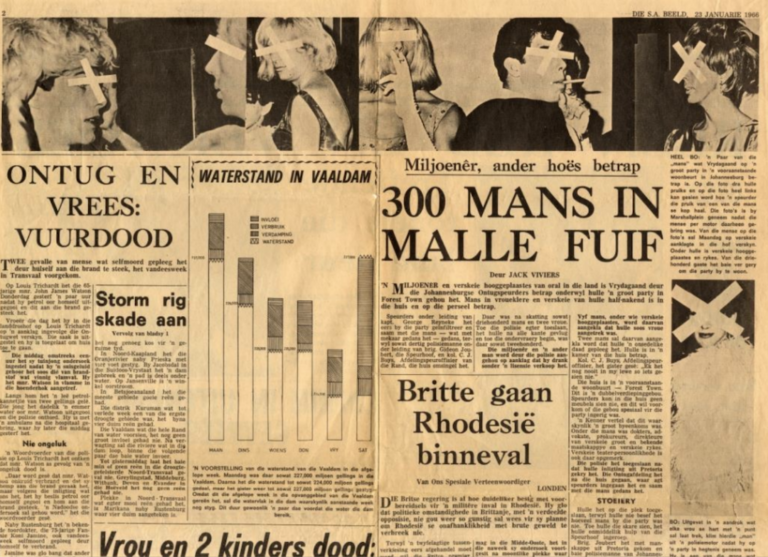

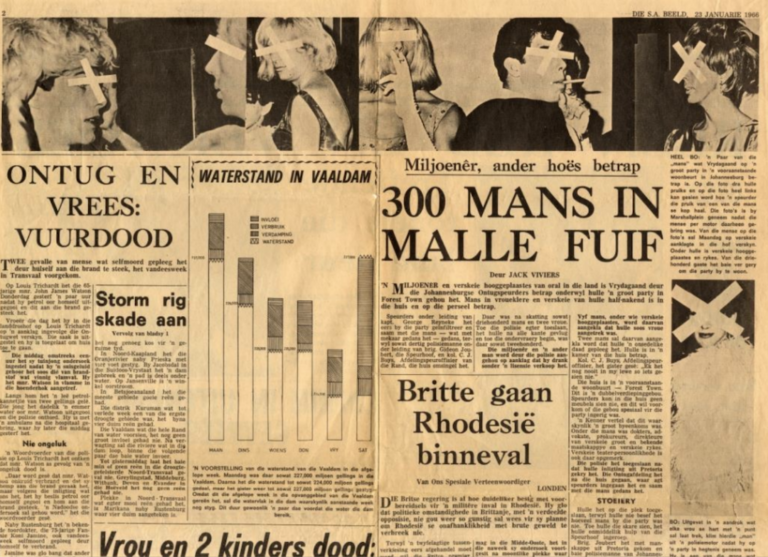

The Forest Town Raid in Johannesburg

Police raided a party, attended by mostly gay people, in the suburb of Forest Town. Ten men were arrested - nine for ‘masquerading as women’ and one for ‘indecent assault on a minor’. The raid was believed to be “the most organised and most publicised the police had ever attempted” and a turning point that triggered the ban on homosexuality in the private sphere.

“There were approximately 300 male persons present who were all obviously homosexuals … Males were dancing with males to the strains of music, kissing and cuddling each other in the most vulgar fashion imaginable. They also paired off and continued their love-making in the garden of the residence and in motor cars in the streets, engaging in the most indecent acts imaginable with each other.”

- South African Police report to Parliament

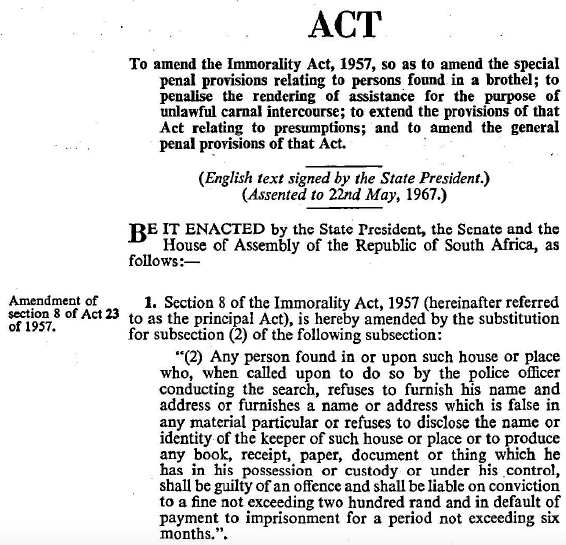

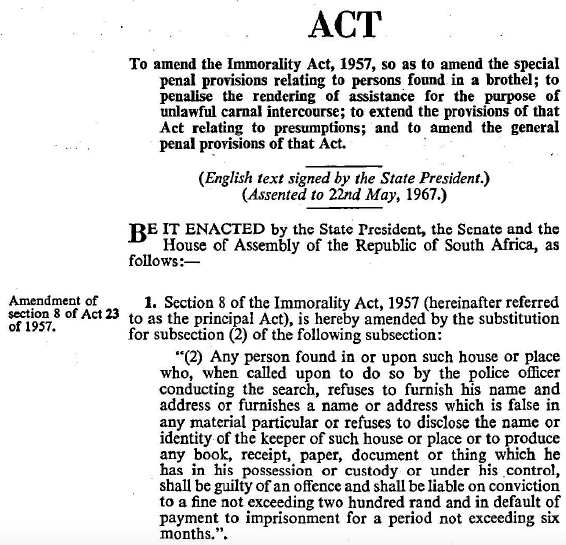

1967

Calls for more stringent legislation

The South African Police requested a change in the law so as to criminalise all homosexual conduct in private. Police agitation resulted in a formal police-driven investigation into homosexuality. The report concluded that “present legislation is quite inadequate to cope with this very real problem”.

1967

A ban on all homosexual conduct including between women

Religious conservative groups pushed for new anti-gay legislation to include the criminalisation of private same-sex relations for gay men as well as lesbian women. Before this, sexual acts between women were technically legal. If the new law was to succeed, it would ban all homosexual conduct, not just conduct between men.

1967

The ‘men at a party’ clause in the Immorality Amendment

The ‘men at a party’ clause, criminalised all sexual acts between men at a party - with ‘party’ referring to a gathering of more than two people. This enabled certain intrusions into private life as well as forbidding gay parties.

1968

Parliamentary Select Committee’s investigation into homosexuality and the ban of dildos

A Parliamentary Select Committee, set up to research homosexuality, called for confidential submissions on the topic from the general public and government officials. Following a discussion of homosexual men, the Committee turned its focus to lesbians. Their concerns centred around the size of dildos that were considered to be larger than ‘normal’ penises. They believed this would ruin a woman’s ability to gain sexual pleasure from a man. The police urged for a ban on dildos as a strategy ’to stop lesbianism.’

“As with every virulent infection, it [homosexuality] spreads.”

-Major F.A.J. Van Zyl, then South African Police representative on the Select Committee

Media Online

1968

“Leave us alone!”

A 1968 Golden City Post article titled “Leave Us Alone, Moffies Plead” urged ‘moffies’ to speak out against government sanction. Kewpie, a well-known performer and activist in Cape Town warned “people should not try to interfere with our community. Nobody can change us.”

The South African Medical Journal also published an editorial and asserted that homosexuality “requires understanding and help, not debasement and punishment.” The Society of Psychiatrists and Neurosurgeons of South Africa started to issue public statements against criminalisation and campaigned “against what it perceives as harsh policies towards mentally ‘ill’ individuals.”

Media Online

1968

The Law Reform Movement challenges the penalisation of same-sex relationships

White gay and lesbian groupings banded together to form the Law Reform Movement to fight prosecution. The first gay public meeting ever held in South Africa took place on 10 April 1968. The strategy of this group involved lobbying lawmakers to soften the legal amendments that were being considered.

One of its sub-committees prepared submissions to Parliament; another compiled leading psychological and scientific research concerning homosexuality; and a third was dedicated to fundraising by holding events across the country in members’ homes and private settings.

The fundraising committee also hosted a public meeting at the Park Royal Hotel near Joubert Park in Johannesburg - the first general meeting of gay men and lesbians in the history of the country.

“Gay life flourished and there were more parties than ever before. People seemed to forget their differences, and everyone pitched in.”

-‘Hannah’, participant in the Law Reform Movement

1969

“We fought back and won”

The Law Reform Movement celebrated the fact that the new legislation continued to criminalise homosexual conduct at parties but did not extend to homosexual acts in private. The movement had achieved an important goal of securing the rights of gay people to privacy in their sexual lives. Following this, the movement disbanded but this stands as a foundational moment in LGBTQIA+ history.

“We had done it ourselves. We were threatened and we fought back and won. For the very first time. It felt great!”

-Law Reform member

“The essence of the approach was that innocent members of society must be protected against the effects of homosexuality without penalising homosexuals for deviations from social norms they could not help.”

-Cape Argus

1970 - 1999s

The Aversion Project to ‘cure deviants in the army’

The South African Defence Force forced hundreds of white gay and lesbian conscripts to undergo medical treatment without their consent to try and convert them to heterosexuality. An exposé by the Mail & Guardian in July 2008 estimated that about 50 sex-change operations were performed every year between 1971 and 1989 and that gay conscripts were subjected to ‘narco-analysis’ and ‘conversion therapy’ which involved a ‘patient’ being subjected to electric shocks while being shown gay pornographic images.

The National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and other human rights activists launched a campaign for a government inquiry into this project in the 1990s.

1970s

Bars, spaces and underground networks

To avoid reprimand or arrest, the gay community operated largely underground. Gay bars and clubs, such as the Butterfly Bar in Hillbrow, created new spaces for people to meet and interact. Despite threats of prosecution, white gay life continued to thrive in Hillbrow over the next ten years.

1972

The South African Gay Liberation Movement

is banned

In 1972, Mark West, then a student at the University of the Natal, founded the South African Gay Liberation Movement stating that, “I believe, as do my followers, that homosexuals should come forward and demand their rights. We should not be forced to meet in dark bars.” It took only three weeks for the police to force West to shut the movement down - a clear warning to gay activists that political action would be repressed vigorously.

1980

Raids and renewed harassment

After the police raided Mandy’s, a popular gay bar in downtown Johannesburg, a sense of political frustration among the almost exclusively white, middle-class attendees was reignited. They formed Lambada along with three gay supper clubs: the 6010 Club in Cape Town and the Alternative Men’s Organization (AMO) and Unite, both in Johannesburg.

1982

The Gay Association of South Africa (GASA)

Lambda, AMO and Unite merged to form GASA, the first national gay organisation in the country. Its aim was to create social and community spaces where gays and lesbians could gather without fear of sanction rather than to challenge the government directly.

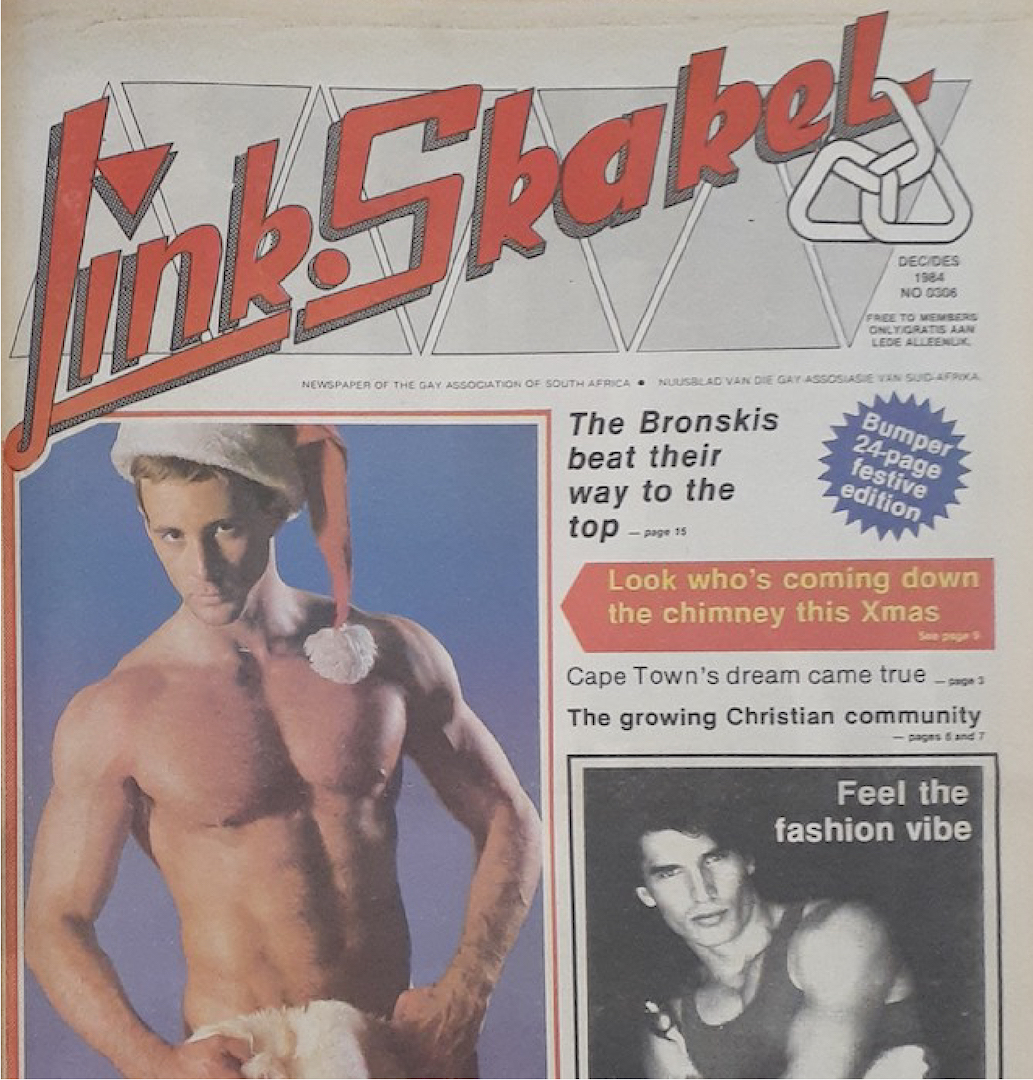

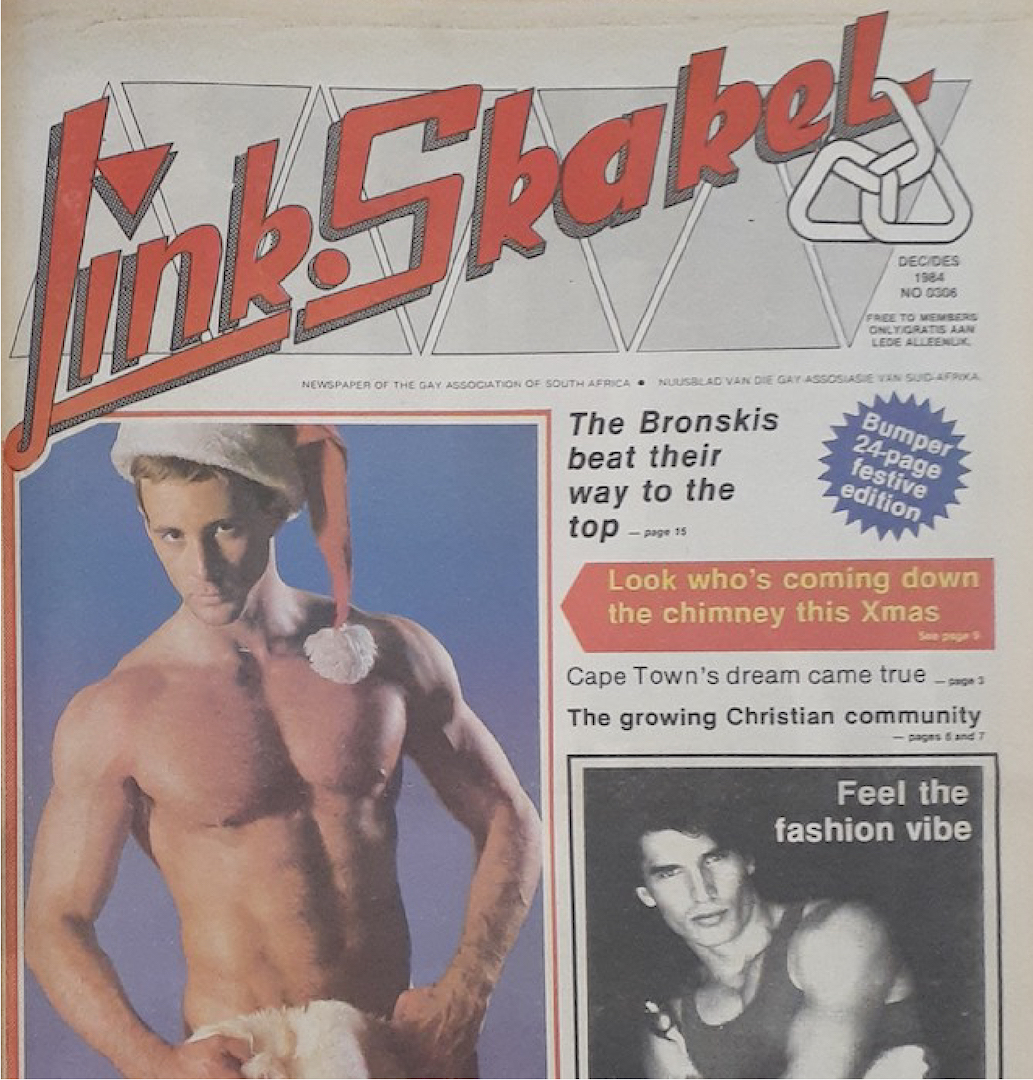

GASA quickly launched an awareness campaign ‘Operation Snowball’, published their magazine Link/Skakel, and built several branches across the country, providing an invaluable connection to the gay community for individuals who lived in rural areas.

1982

HIV/AIDS stigma and awareness campaign

Ralph Kretzen and Pieter Daniël (Charles) Steyn, who died within four months of each other in 1982, are officially recognised as the first two people to die of AIDS in South Africa. After their death, a media frenzy ensued and the growing AIDS crisis unleashed a new wave of homophobic paranoia across the country. Gay men were blamed for transmitting a deadly plague.

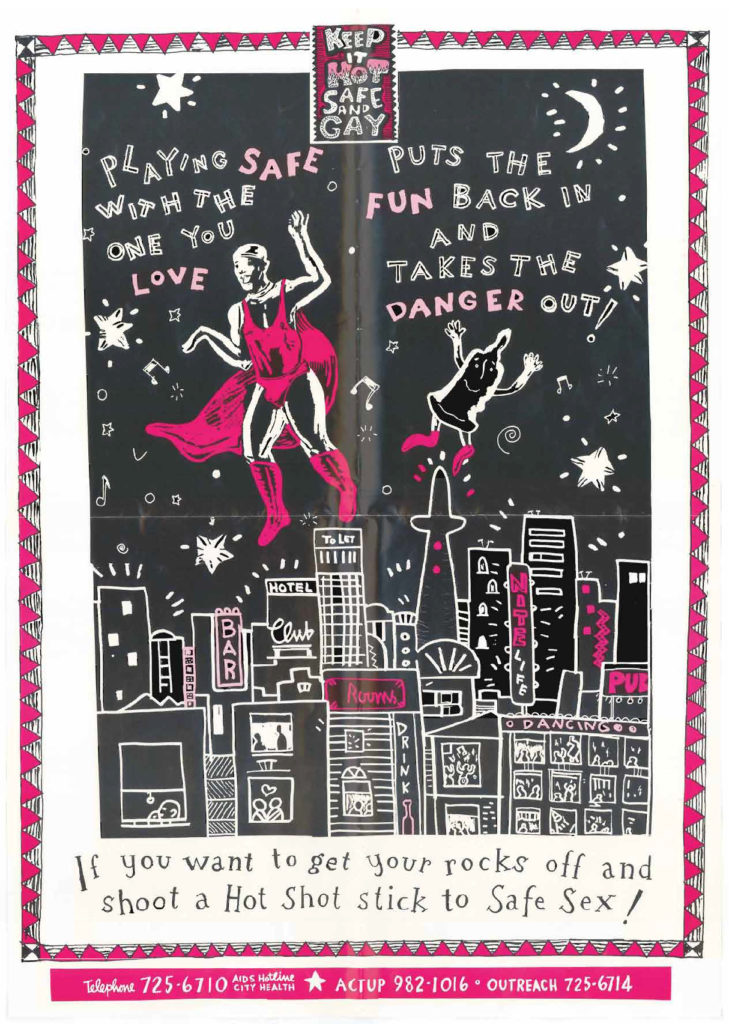

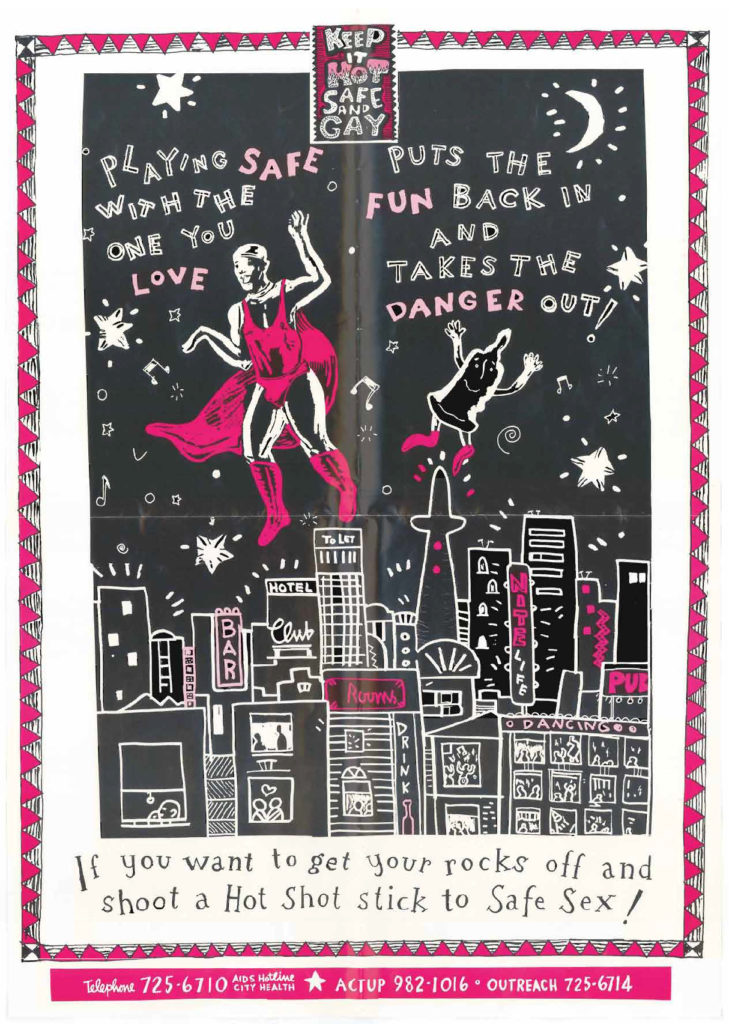

While GASA’s leadership took the threat of AIDS seriously, this was not true of the general gay community. In 1983, GASA National established an AIDS fund. Cape Town’s 6010 Group started an HIV/AIDS awareness campaign which culminated in the formation of the AIDS Action Group in 1984. Pamphlets, posters and comic strips such as those used in the ‘Keep it hot, safe and gay’ campaign, proved an effective tool in other awareness actions.

1970 - 1980

Underground publications

During the 1970s and 1980s, gay rights organisations published newsletters and magazines despite the fear of censorship and prosecution. Equus “promoted gay venues, allowed people to share feelings, and included pin‐ups of local men.” Comment had a more activist agenda. The July 1982 edition of Gay Association of South Africa’s (GASA) Link/Skakel declared that “A very definite need exists amongst gays of all walks of life, to do something … to improve the lot of gays in South Africa.”

In August 1984, the Publications Review Board declared GASA’s Link/Skakel ‘undesirable’ stating that the magazine was “calculated to promote homosexuality which ... is an offensive and immoral form of sexual activity … This publication would exceed the tolerance of the average decent minded citizen.” GASA could no longer sell its magazine publicly but was allowed to continue distributing privately.

The early 1980s

A proliferation of gay rights groups organisations

Several diverse local organisations were established within the LGBTQIA+ community including the non-denominational Gay Christian Community (GCC), the Lesbians in Love and Compromising Situations (LILACS) and the Transvaal Organisation for Gay Sport (TOGS). The plethora of new oganisations marked the start of overt activism for gay rights. However, there were significant tensions within the LGBTIA+ community. Whether or not to oppose apartheid and affiliate with the broader political anti-apartheid movement became a key source of division in the years to follow.

1983

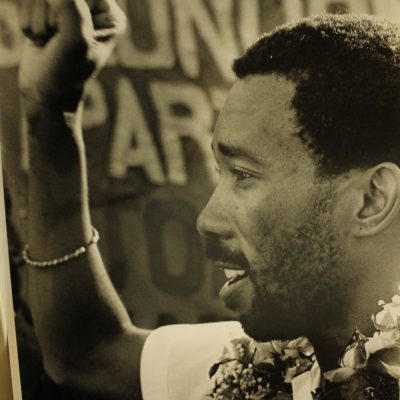

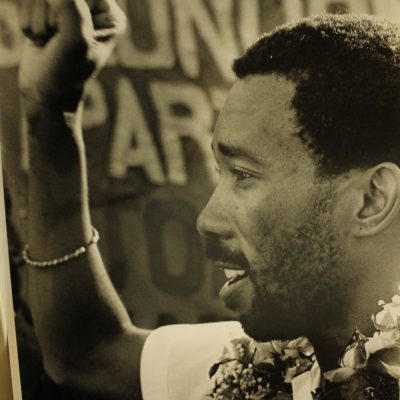

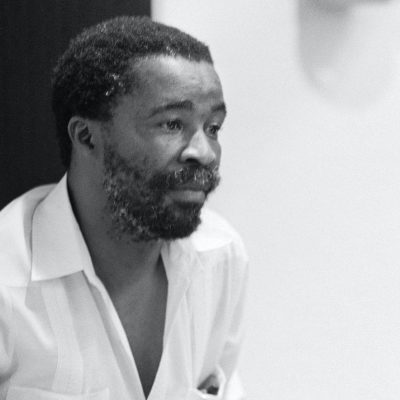

Simon Nkoli’s Saturday Group

Simon Nkoli, along with his partner Roy Shepherd, established the Saturday Group as an alternative space for GASA’s black membership. Simon Nkoli explained that it “was very much concerned about mostly the black gays who don't come out of the closet. This group was trying to form a black gay group in Soweto and elsewhere in the country.”

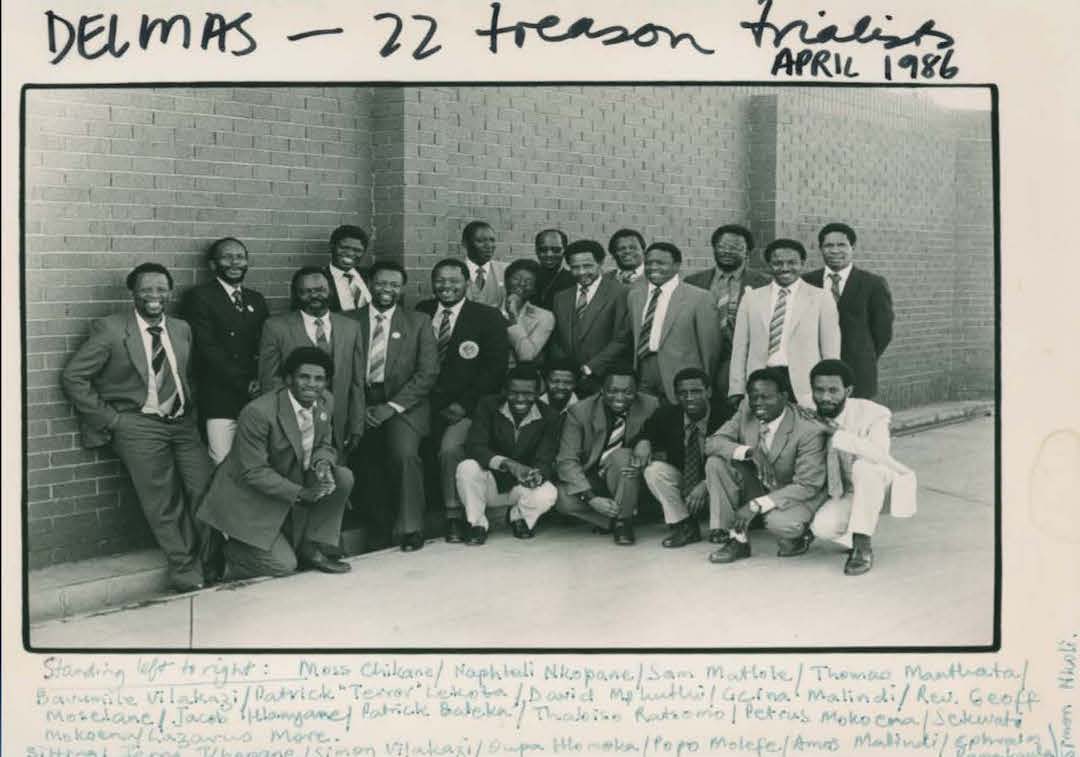

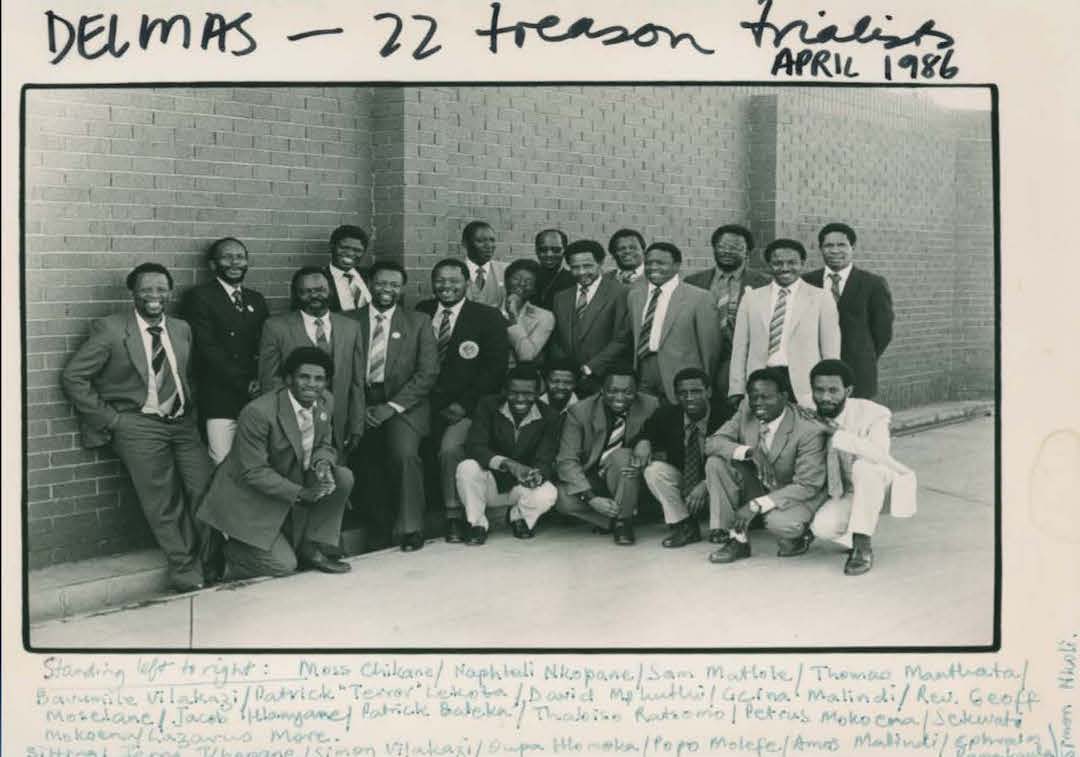

1985 - 1988

The Delmas Treason Trial

Shortly after the launch of the Saturday Group, Simon Nkoli, along with 21 other United Democratic Front (UDF) leaders, were arrested and charged with ‘subversion, conspiracy, and treason’. These charges potentially carried the death sentence. A four-year trial – the longest political trial in South Africa - began in the small town of Delmas.

Whilst in prison, Nkoli came out to his co-accused during a heated debate about homosexual behavior in jail. Many of his co-trialists were shocked initially. They condemned homosexuality and demanded that Nkoli be tried separately believing that the state could use Nkoli’s homosexuality to discredit the trialists and the moral standing of the UDF as a whole. But Nkoli’s unique combination of charm and perseverance, and on the insistence of the team advocates that there should be one trial for all, Nkoli’s comrades were won over.

"Simon's coming out during the Delmas trial was pivotal. When he was sidelined by the other trialists in prison, Simon responded with outrage and confronted senior UDF activists including Terror Lekota and Popo Molefe. He claimed his queerness and his anti-apartheid social justice activist role as inseparable. I credit him with re-shaping the LBGTI movement. Simon's remarkable history shows the power of coming out – his assertive visibility and resistance laid the path for our inputs into the constitutional negotiating process.”

-Edwin Cameron, LGBTI rights activist, lawyer, and later Constitutional Court judge

Prejudices challenged and the Non-Stop Picket

Nkoli’s attendance at a GASA meeting was a crucial point in countering the prosecution which had tried to place him at the scene of a murder. This brought the trial to the attention of the international gay rights movement. Canadian activists established the Simon Nkoli Anti-Apartheid Committee (SNAAC) and were joined by other international organisations. Local activists also protested his detention.

Simon received hundreds of letters of support whilst in detention. This not only boosted his morale but helped challenge the prejudices of his co-accused. These acts of solidarity helped raise Nkoli’s profile as a gay anti-apartheid militant which, in turn, fuelled the struggle for lesbian and gay rights.

During his imprisonment, Nkoli learned that he was HIV positive. A ‘victory’ rally for Nkoli was held by the Non-Stop Picket - the continuous protest, day and night outside the South African Embassy in central London.

1986 - 1987

Formation of Lesbians and Gays Against Oppression (LAGO) and the Organisation of Lesbian and Gay Activists (OLGA)

GASA refused to condemn apartheid or make public its indignation about the arrest of Simon Nkoli, stating that “Had Gasa made representations on a political level, we may well have been annihilated.” In 1986, LAGO was then formed in Cape Town. Julia Nicol, one of LAGO’s founding members explained that “We felt it was essential for a specifically gay/lesbian voice to be speaking out against apartheid. GASA has emphatically failed to do this, and nor was it being done by any of the smaller organisations at the time. We felt that to do so was vital for both the sake of our self-esteem as lesbian/gay individuals and for the sake of the image of the gay community in the eyes of the anti-apartheid movement.”

Internal dissent led to the dissolution of the organisation in October 1987 and members reorganised as OLGA. Links were cemented with anti-apartheid organisations.

1985

An end to the ban on interracial relationships

In June 1985, the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act was repealed. A later report estimated that a total of 929 persons had been arrested, 829 charged, 733 brought to trial, 221 acquitted, and 527 found guilty in terms of section 16 of the Immorality Act of 1957. While people could now legally engage in relationships across the colour bar, provisions criminalising homosexuality remained.

1980's

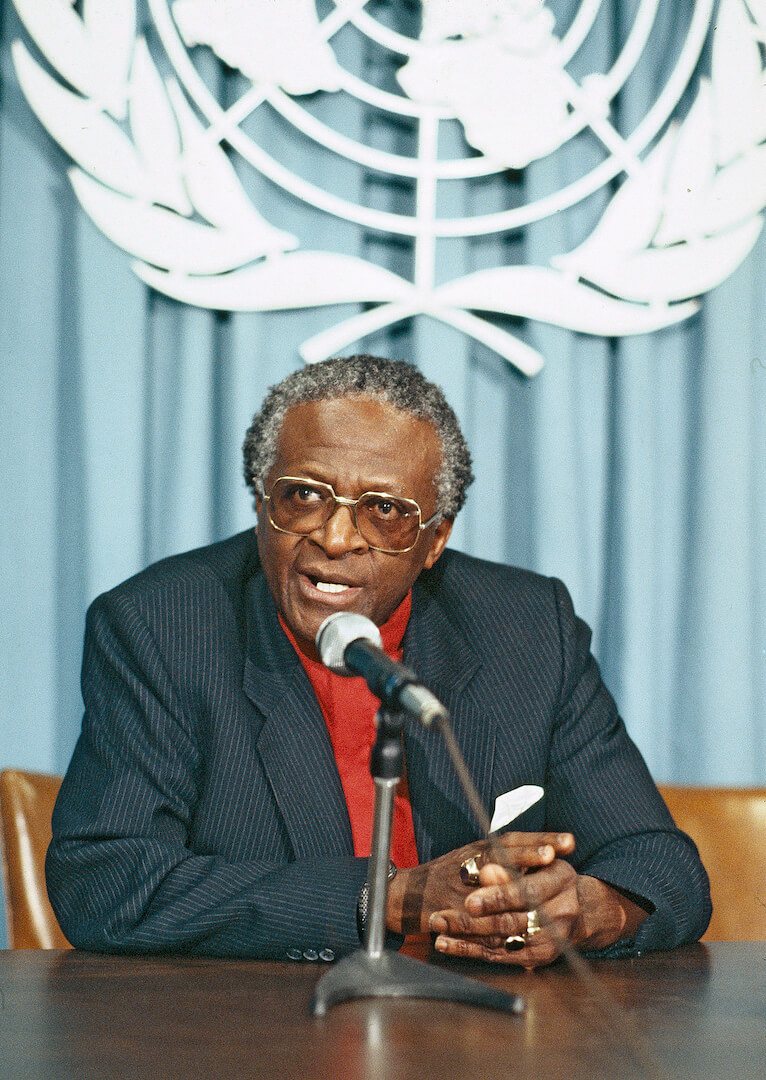

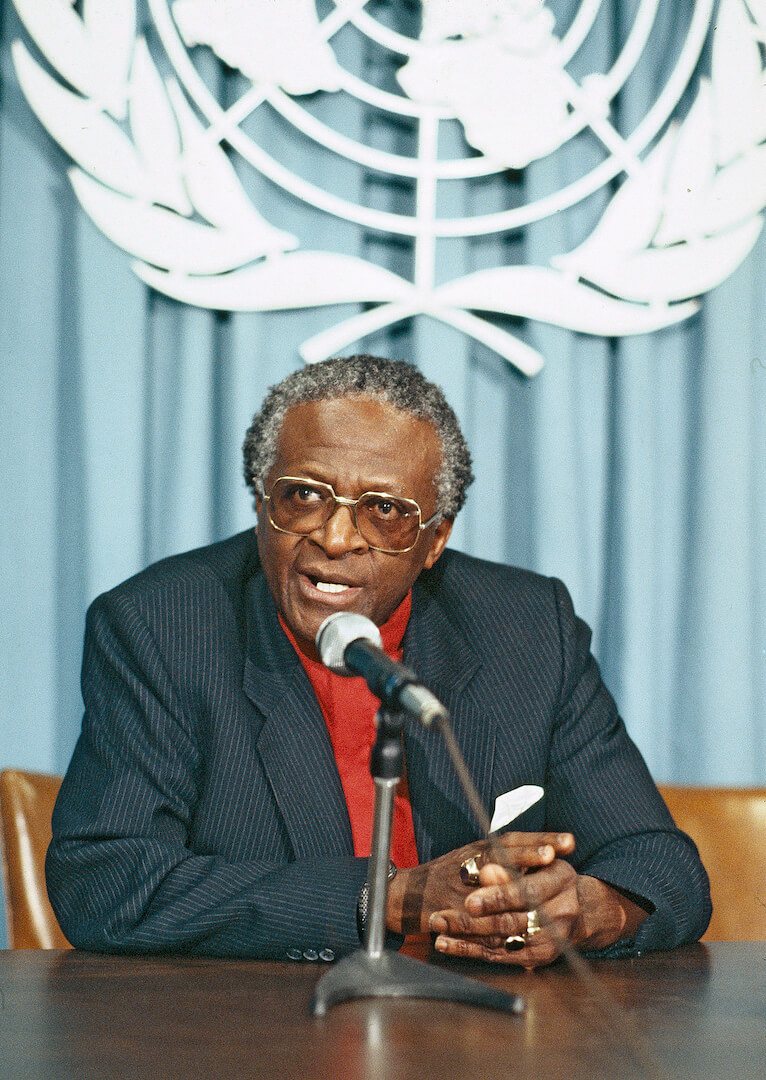

Archbishop Tutu condemns homophobia as blasphemy

Archbishop Tutu - known the world over for his prominent role in the campaign against apartheid – is also known for his strong advocacy on issues of sexuality, in particular the rights of lesbian and gay people. Tutu’s equation of black civil rights and lesbian and gay rights stems from his theological conviction that every human being is created in the image of God and therefore is worthy of respect.

In the early 1980s, he applied the word ‘heresy’ to denounce and condemn apartheid stating that, “Apartheid’s most blasphemous aspect is … that it can make a child of God doubt that he is a child of God”. Some years later wrote he used similar words to denounce homophobia. He said that it was the ‘ultimate blasphemy’ to make lesbian and gay people doubt whether they truly were children of God and whether their sexuality was part of how they were created by God. His position can be summed up in his succinct statement made in 2013: “I would rather go to hell than to a homophobic heaven”. The issue of homosexual clergy remains unresolved in the Anglican church to this day.

“If the church, after the victory over apartheid, is looking for a worthy moral crusade, then this is it: the fight against homophobia and heterosexism.”

-Archbishop Tutu, shortly after the end of apartheid in 1994

1985 - 1988

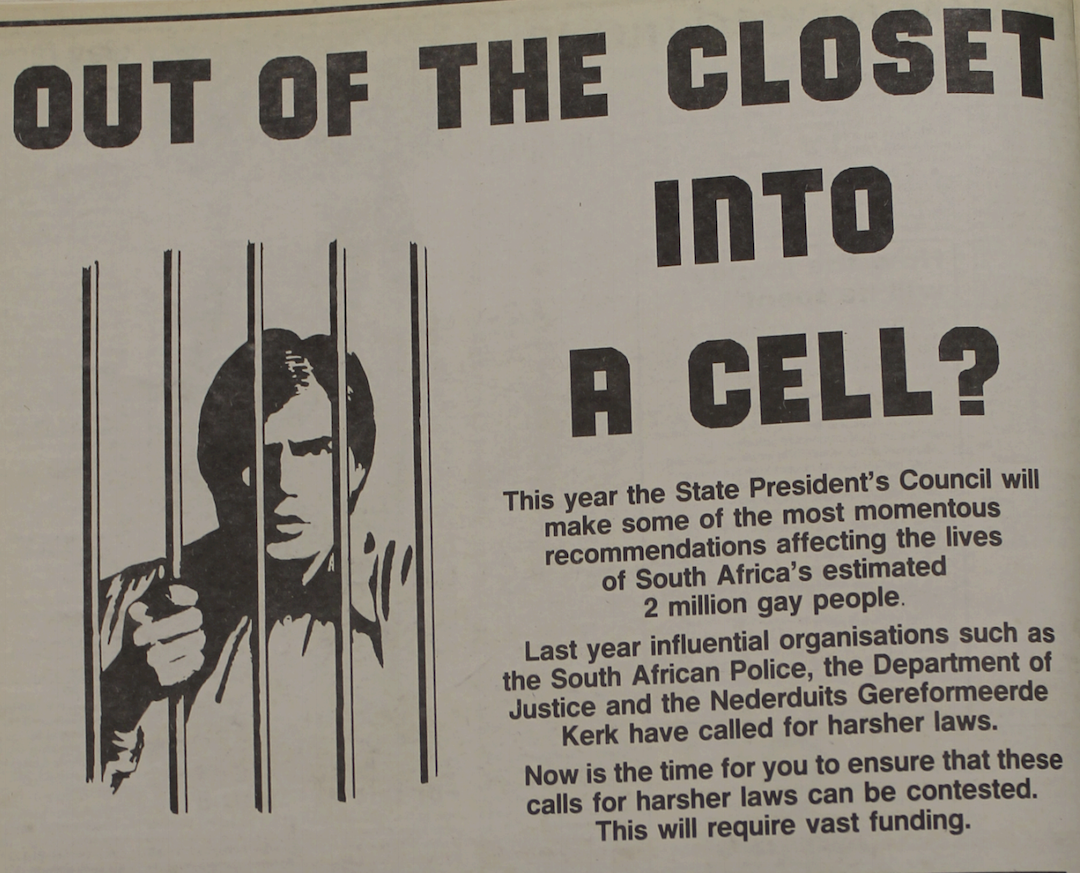

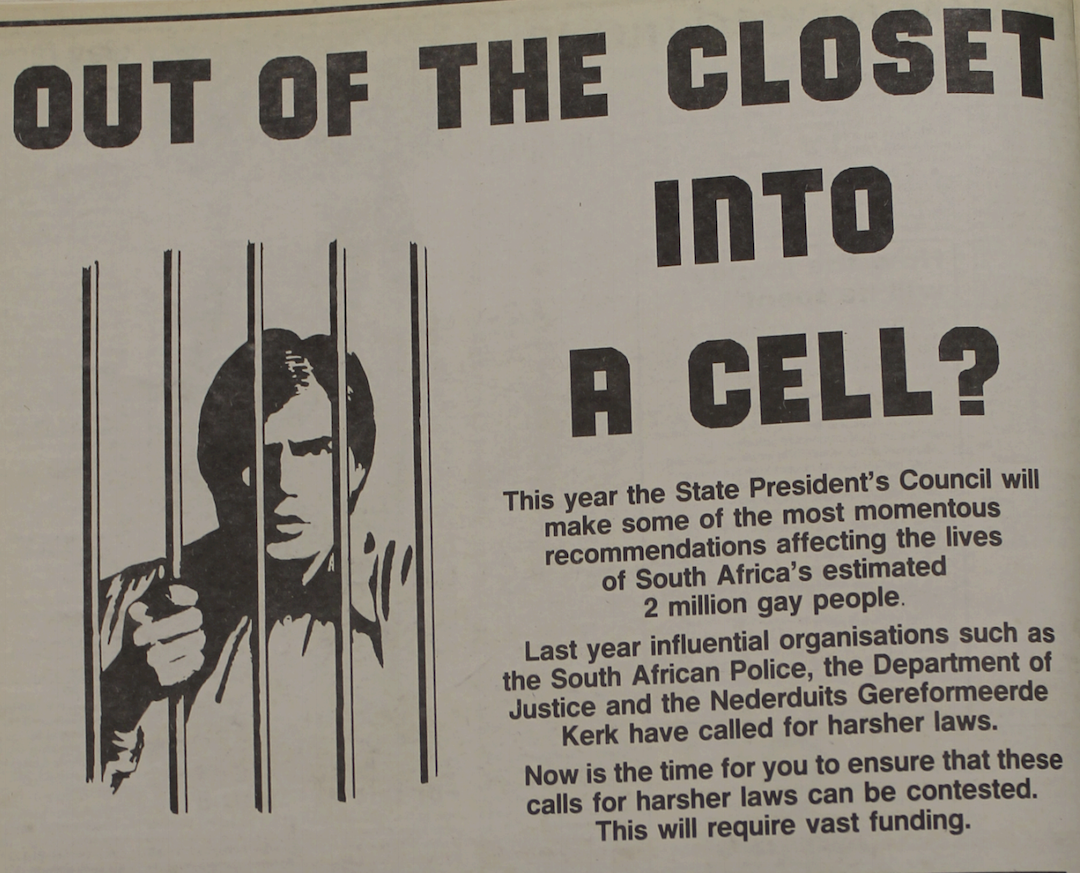

The ‘Out of the Closet and into a Cell’ campaign

GASA revived the Law Reform Fund and launched its campaign to demand the decriminalisation of homosexuality. They wrote an 18-page memo which was one of eleven memos submitted to the President’s Council that called for decriminalisation. However, five other memos, submitted by churches and government departments, urged for the continued criminalisation of homosexuality. In the end, the State President’s Council retained criminalisation stating in their 1987 report that, “Homosexuality in men and in women is a serious social deviation … The fact that homosexuality is increasingly regarded as normal by the community is cause for concern.”

1987

Challenging homophobia within the ANC

In 1987, Peter Tatchell, a well-known British political activist and participant of the anti-apartheid movement since 1971, raised the issue of the failure of the ANC to confront homophobia. He referred specifically to an interview with Ruth Mompati, then a member of the ANC’s National Executive Committee (NEC) and a courageous fighter against the apartheid regime, where she said: “I hope that in a liberated South Africa people will live a normal life ... I emphasise the word normal … Tell me, are lesbians and gays normal? No, it is not normal I cannot even begin to understand why people want lesbian and gay rights … The (gay) issue is being brought up to take attention away from the main struggle against apartheid … They are red herrings.”

Solly Smith, the ANC’s chief representative in London, confirmed that the ANC did not have a policy on lesbian and gay rights and refused to comment on whether an ANC government would repeal anti-gay laws. An outcry erupted among lesbians and gays who were supportive of the anti-apartheid struggle when Tatchell published these comments in Capital Gay, a major lesbian and gay newspaper in London.

12 October 1987

A letter to Thabo Mbeki

Consequently Tatchell wrote a letter to Thabo Mbeki, then ANC Director of Information:

“Dear Thabo Mbeki,

Given that the Freedom Charter embodies the principle of civil and human rights for all South Africans, surely those rights should also apply to lesbians and gays? And surely the ANC should be committed to removing all forms of discrimination and oppression in a liberated South Africa? … To me, the fight against apartheid and the fight for lesbian and gay rights are part of the same fight for human rights.

Yours in comradeship and solidarity, Peter Tatchell.”

24 November 1987

The development of an ANC policy on sexual orientation

The ANC leadership in exile worked to develop a clear policy on LGBT issues. After several weeks, Tatchell received a reply from Mbeki on 24 November 1987.

1988

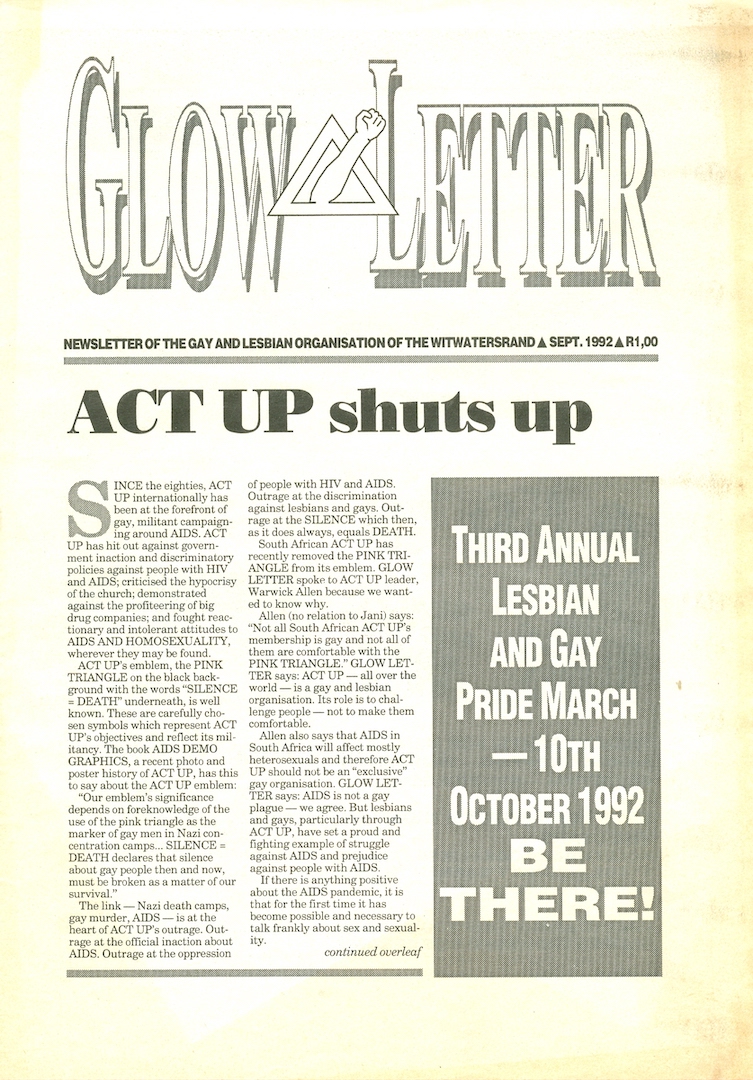

The formation of Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW)

GLOW was founded to create an explicitly non-homophobic, non-racist, and non-sexist space for gays and lesbians living in and around Johannesburg. GLOW aligned itself with anti-apartheid groups like the ANC and the UDF and was explicitly racially and politically inclusive although it did not formally affiliate itself to any one political organisation. Founding member, Simon Nkoli, stated, “I am black, I am gay, I cannot separate the two parts of myself into secondary or primary struggle. They are one.”

Another founding member, Beverley Palesa Ditsie, passionately called for an end to shame: “Gay people had been relegated to living in the shadows, on the margins, living in shame and subjected to all sorts of abuses and injustices and we had had enough. Even further, the accepted notion from our black families and communities was (and still is) that we are un-African and trying to adopt some mindless, pointless Western existence — or even worse, an existence that intends to destroy Africa and Africanism.”

GLOW’s expansion

GLOW chapters were formed across the city in places as diverse as Hillbrow, Soweto, and Yeoville. The KwaThema branch was one of the organisation’s most active chapters boasting its own headquarters - MaThoko’s house where Thokozile Khumalo opened her home to countless young LGBTQIA+ people for more than a decade.

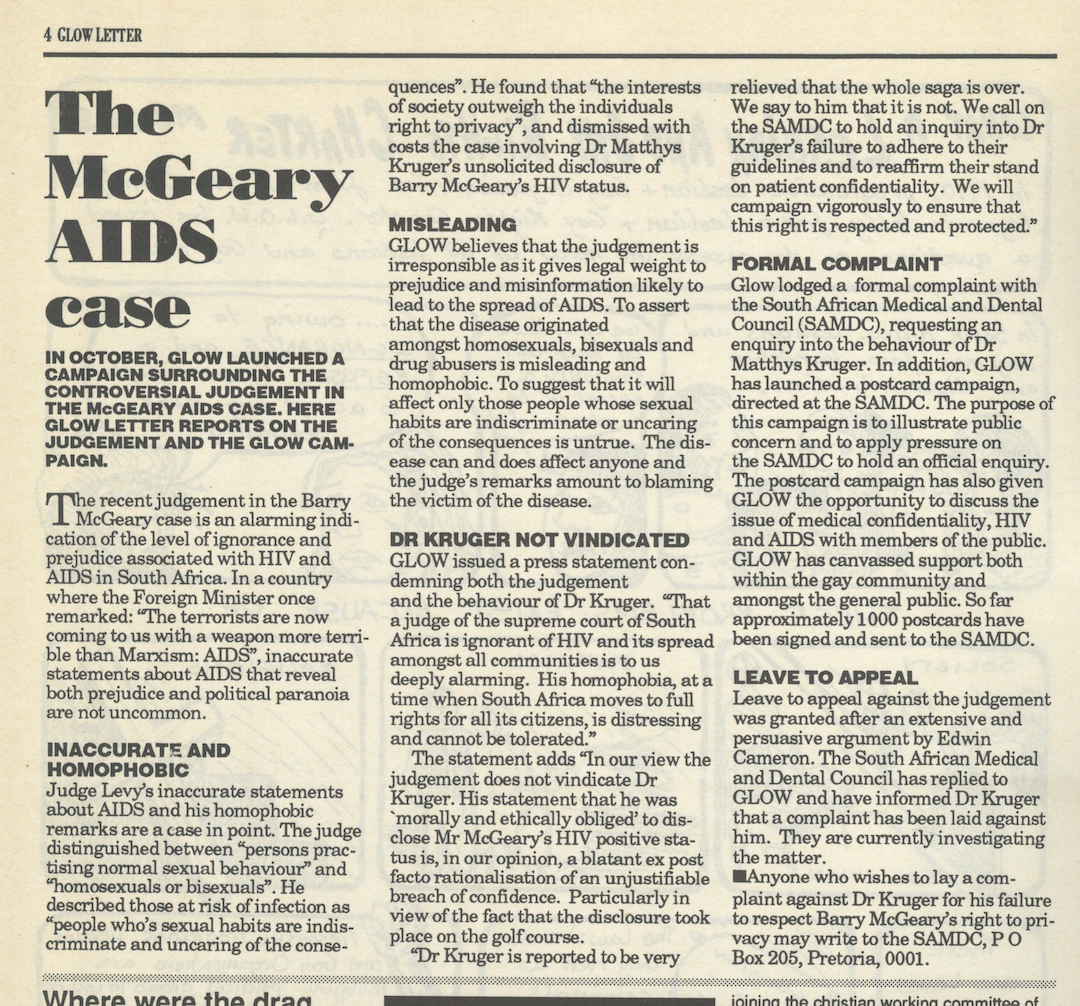

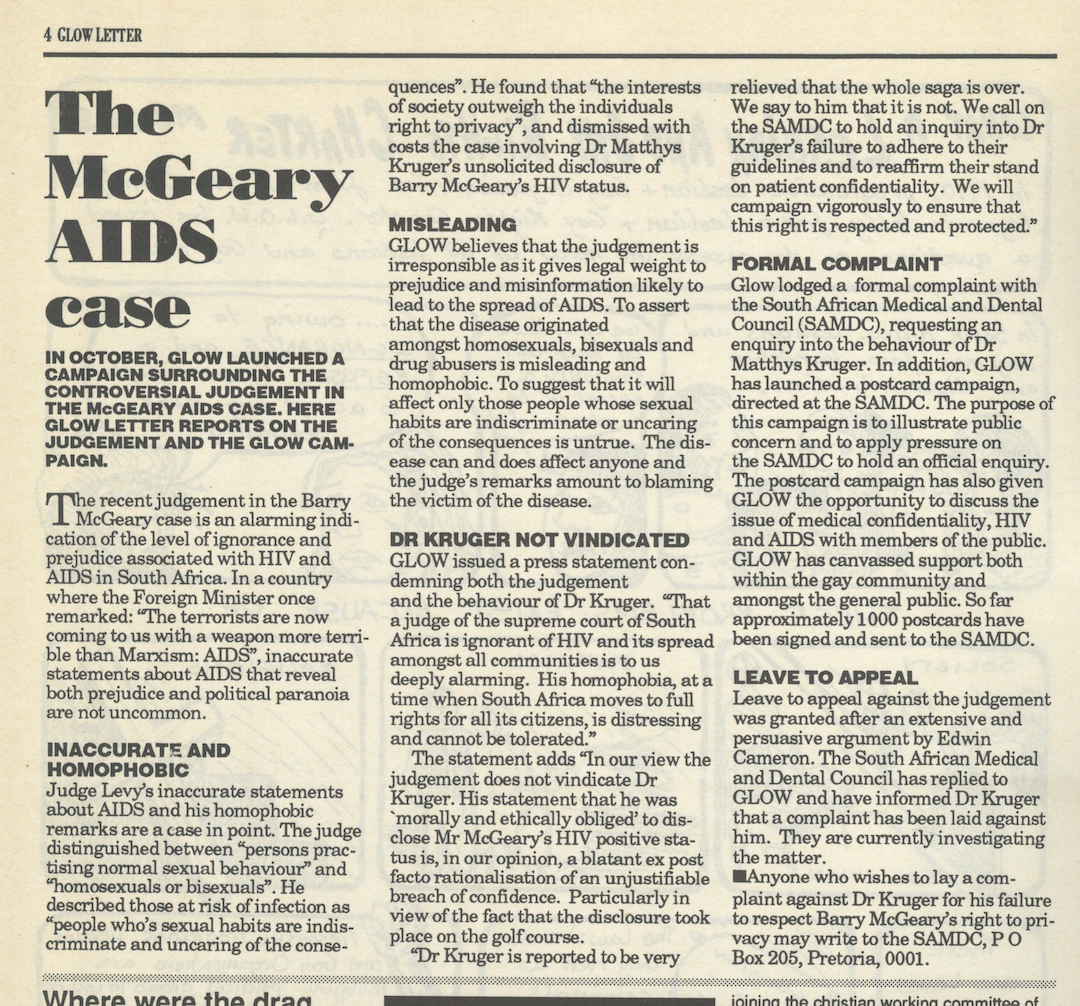

GLOW and HIV/AIDS activism

GLOW participated in legal cases around gay rights issues and HIV/AIDS, most notably the case of Barry McGeary, a businessman living with AIDS whose doctor revealed his HIV/AIDS status to friends while playing golf. GLOW and the South African branch of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) protested this notification as breaching patient confidentiality. As a result of petitions by community members and letters to the South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC), Doctor Kruger was found guilty of disgraceful conduct and was suspended.

1988 - 1989

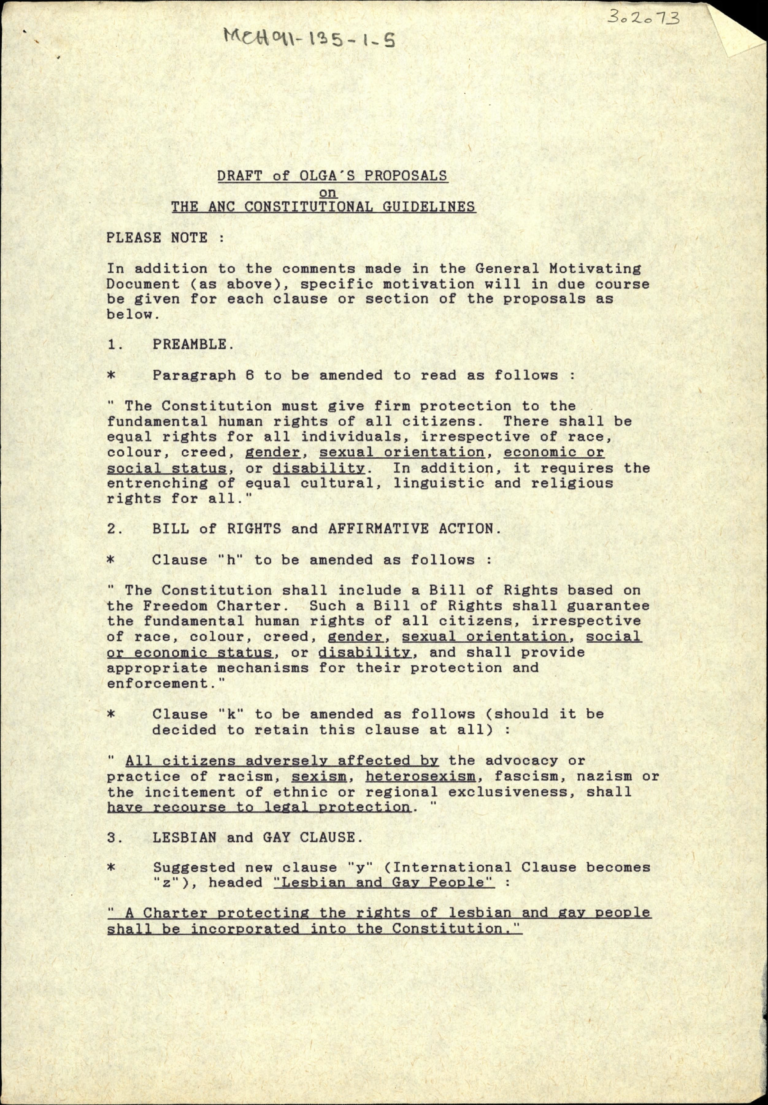

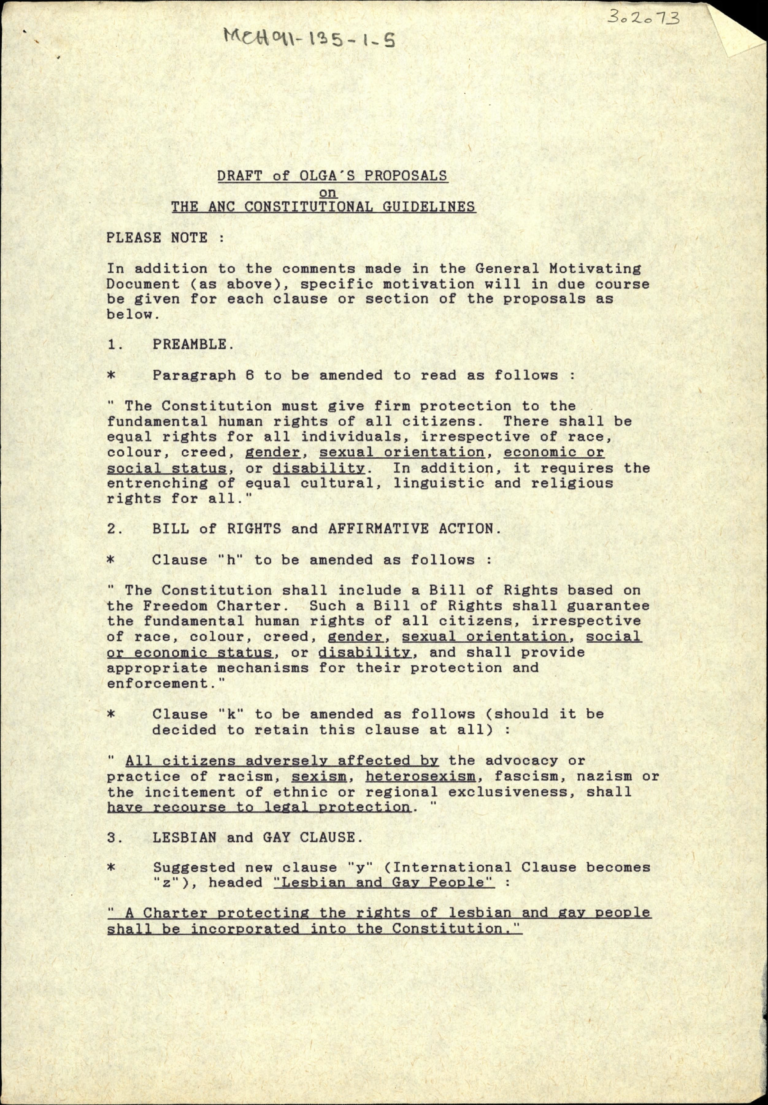

The ANC’s Constitutional Guidelines and the sexual orientation clause

As circulated in 1988, the ANC’s Constitutional Guidelines confirmed the ANC’s commitment to multi-party democracy, an enforceable bill of rights, progressive social and economic reforms and a commitment to combating sexism. There was no explicit guarantee of gay rights or the prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation. The issue of the ANC’s approach to sexual orientation was formally raised at the “In-House Seminar on Women, Children and the Family in a Future Constitutional Order” in Lusaka in December 1989, organized by Zanele Mbeki and the Women’s Section of the ANC. It was a decision-making gathering which determined that the prohibition of discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation was formally part of ANC policy.

1989/90

The issue is put firmly on the agenda

Several lobby groups who desired constructive engagement on the issue of gay rights in post-apartheid South Africa, approached exiled ANC leaders who were working on drafting a democratic constitution for a free South Africa. In December 1989, for example, OLGA representatives, Derrick Fine and Niezhaam Sampson met with Albie Sachs in London to have a face-to-face discussion on OLGA’s constitutional proposals for a clause prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation. In a letter sometime after the meeting, Fine and Sampson confirmed its importance:

“… our members held discussions with cde Albie Sachs in London on the subject of the ANC Constitutional Guidelines. Cde Albie indicated that input on the particular concerns and proposals of progressive lesbian and gay organisations in South Africa would be must welcome, and that he would ensure that same were passed on to your Legal and Constitutional Affairs Department for consideration. Since then we have corresponded with cde Albie on progress made in our work on the subject.”

OLGA also engaged with several other senior ANC leaders, who expressed support for their constitutional proposals.

December 1989

ANC makes non-discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation an official policy

The ANC’s ‘In-House Seminar on Women, Children and the Family in a Future Constitutional Order’ was a policy making seminar examining law and legal institutions with a view to eliminating ‘pernicious gender discrimination’. Time was allocated to a discussion on ‘homosexual and gay rights’. This led to the important decision for the prohibition of discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation to become

ANC policy.

The Constitutional Committee which regarded the issue as one of principled importance were therefore free to incorporate this principle into the ANC’s proposed Bill of Rights. As Albie Sachs recalls, there was no opposition or resistance on the Constitutional Committee: “Kadar [Asmal] and I felt strongly on the issue. Others were happy to go along with inclusion of the clause, even if it was not a matter of special importance to them. The broad feeling would have been - let people be who they are.”

January to March 1990

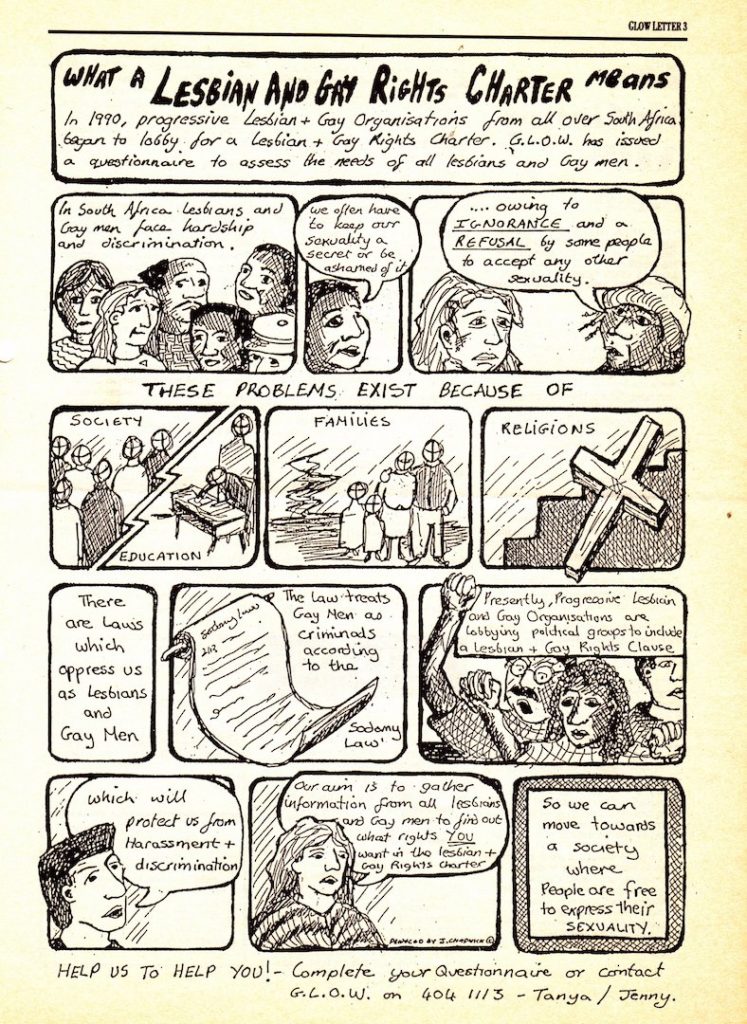

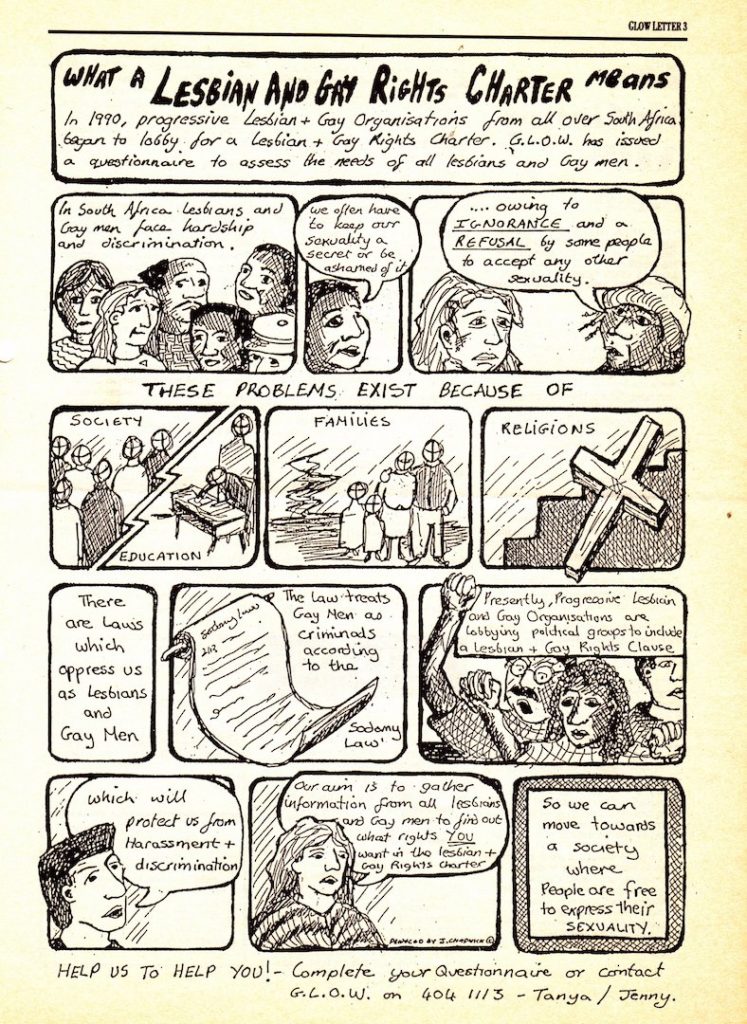

The lesbian and gay rights charter campaign

After the unbanning of political organisations and the release of Nelson Mandela in early 1990, gay rights groups became politically aligned to the UDF and the ANC. Both OLGA and GLOW launched consultative campaigns to gather feedback from gay communities in order to draft a lesbian and gay rights charter.

September 1990

OLGA submits proposal on sexual orientation clause

OLGA submitted a proposal to the ANC’s Constitutional Committee with wording for a sexual orientation clause in a bill of rights that “protects the fundamental rights of all citizens and guarantees equal rights for all individuals, irrespective of race, colour, gender, creed or sexual orientation.”

13 October 1990

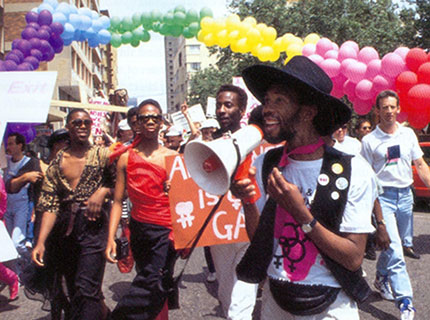

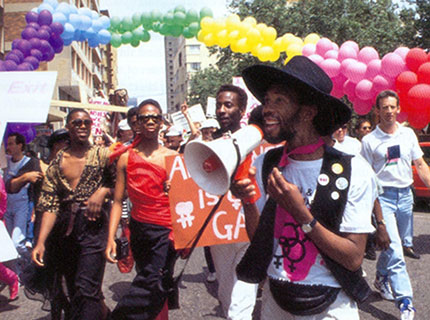

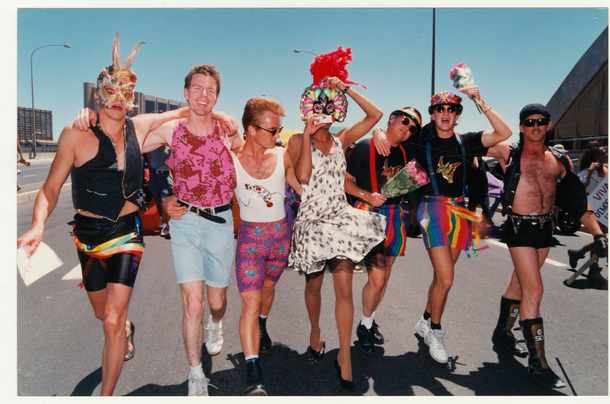

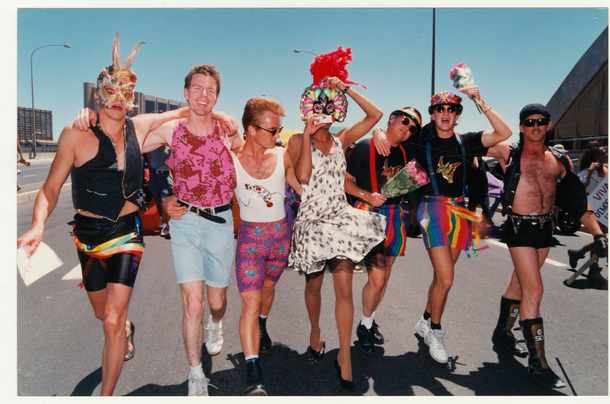

“We’re here, we’re queer, we’re everywhere!” - Pride Marches

GLOW organised the continent's first Lesbian and Gay Pride March on 13 October 1990. Marchers chanted, “We’re here, we’re queer, we’re everywhere!” through the streets of Hillbrow and Braamfontein. Fewer than 1 000 people took part in the march as many participants were afraid of exposure and public scrutiny. Organisers offered participants brown paper bags to wear to conceal their identity. Beverley Palesa Ditsie, then GLOW member, explained that, “We understood that Pride was a political act, an act of protest at these injustices as well as a celebration of our existence. We were no longer begging for our freedom. We were taking it.”

November 29 - 2 December 1990

The Gay Rights Clause in the Draft Bill of Rights

The seminar entitled ‘Gender Today and Tomorrow – Towards a Charter of Women’s Rights’ was the first organized forum to discuss the ANC’s draft Bill of Rights. Brigitte Mabandla, a member of the ANC Constitutional Committee, summarized the draft Bill of Rights for the seminar participants, and noted that “the principle of non-discrimination and non-sexism permeates the draft”. She identified Article 7, which contained the gay rights clause, as “the principal clause on gender equality” and emphasized that “it focuses specifically on equality between men and women and explicitly outlaws discrimination in all its forms”.

She then described the provisions of Article 1 and Article 7 as “creative formulations meant to incorporate the demands of women made at the ANC in-house seminar in 1989.” Mabandla’s statement confirmed that the gay rights clause can be traced to the 1989 Seminar.

November - 2 December 1990

ANC seminar, ‘Gender today and tomorrow - Towards a Charter of Women’s Rights’

This was the first organised forum at which the ANC’s working document on A Bill of Rights was tabled for discussion. Brigitte Mabandla identified Article 7, which contained the gay rights clause, as “the principal clause on gender equality.”

Bridgitte Mabandla then described the provisions of Article 1 and Article 7 as “creative formulations meant to incorporate the demands of women made at the ANC in-house seminar in 1989.” Mabandla’s statement confirms that the gay rights clause can be traced to the views expressed at the 1989 Seminar.

May 1991

Homophobic Slander in Winnie Mandela’s Trial

In this trial, the defence team painted Winnie Mandela as rescuing four young black men from homosexuality which they portrayed as a perversion and a product of colonialism and apartheid. Outside of the courthouse, several Winnie Mandela supporters picketed and displayed placards brandishing statements such as ‘Homosex is not in black culture’.

A few years later Cheryl Carolus, then ANC Deputy Secretary-General, had this to say at a conference on Human Rights Day:

“Our views as the leadership are not necessarily the ones stated by the membership … Many people that we love dearly – our parents, our brothers and sisters, our priests, our teachers are themselves quite often prejudiced when it comes to homosexuality. We must accept that we are not just confronting bigots, people with horns, but that we need to take on this debate with our families and those closest to us. Only then can we begin to shift the position in society.”

July 1991

The sexual orientation clause is endorsed

At the ANC National Conference in Durban, the draft Bill of Rights was endorsed by the NEC as a whole and the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation was accepted “without a murmur of dissent”. The ANC publicly encouraged a commitment to making gay and lesbian rights a priority during constitutional negotiations. At that stage, it was the only political party in South Africa to make such a commitment.

October 1991

The next Pride March

Johannesburg’s Lesbian and Gay Pride March of 1991, under the inclusive slogan “We’re here, we’re queer, we’re everywhere”, again encouraged LGBT people to speak out and put their issues on the agenda.

December 1991 - May 1992

The CODESA ‘talks about talks’

Delegates of 19 political parties gathered for the first time at the World Trade Centre for the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). Gay and lesbian activist groups continued their lobbying efforts throughout this negotiations period.

“Kevan would do the drafting and I would apply my red pen and then Kevan would submit the proposals to the drafting committees at the Kempton Park negotiations. Without that work, the sexual orientation clause would not have survived in the equality provision. We raised money for this work to free Kevan to concentrate on it. So, a combination of early activism, the lobbying that Kevan and I did throughout the negotiations and the ANC’s willingness to accept the submissions – all made possible by Simon’s stand - culminated in the enshrinement of the sexual orientation clause in the Constitution.”

-Edwin Cameron, LGBTI rights activist, lawyer, and later Constitutional Court judge

March - November 1993

Talks resumed at the MPNP and sexual orientation is debated

After a breakdown of CODESA in late 1992, negotiations resumed in March 1993 at the Multi-Party Negotiating Process (MPNP). Three parties - the ANC, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), and the Democratic Party (DP) - all put forward Bills of Rights that expressly prohibited discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. In the end, these parties’ proposals were adapted. The result was expansive rights protections under Section 8(2) of the Interim Constitution of 1993 which prohibited unfair discrimination, directly or indirectly, on the ground of sexual orientation. A historic, but temporary, victory had been secured. There was still the more public drafting process for the final Constitution to come.

11 December 1993

Cape Town’s first official Lesbian and Gay Rights and Pride March

Gay and lesbian organisations continued to encourage activists to live more freely and promote gay rights as human rights by participating in public marches. The recently formed activist group, Association of Bisexuals, Gays & Lesbians (ABIGALE) composed of mostly African and coloured members, organised its first Pride march themed ‘Out of the Closet, Into the Streets’. Approximately 200 people took to the streets to demand the protections of gay and lesbian rights in the newly democratic South Africa.

“When I saw the marchers ahead coming in my direction in Wale Street near St George's Cathedral, I parked in the Cathedral yard and joined them. Initially I felt awkward as I seemed to be the only straight person and I wished there was a banner saying ‘Straights for Gays’. The right to be different was a key issue to be supported by all South Africans. But the minute I started marching next to Edwin Cameron, I felt immensely proud … It was an important moment for me to be joining in with people fighting for their freedom.”

-Albie Sachs, then member of the ANC Constitutional Committee

13 December 1993

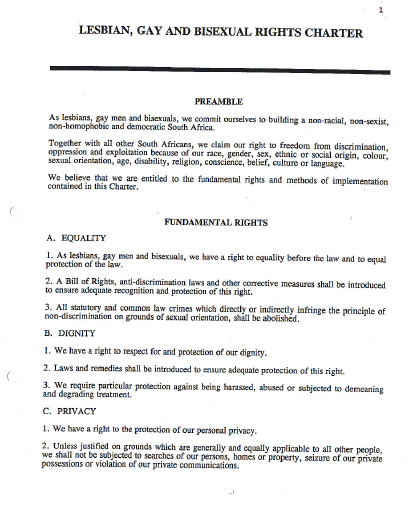

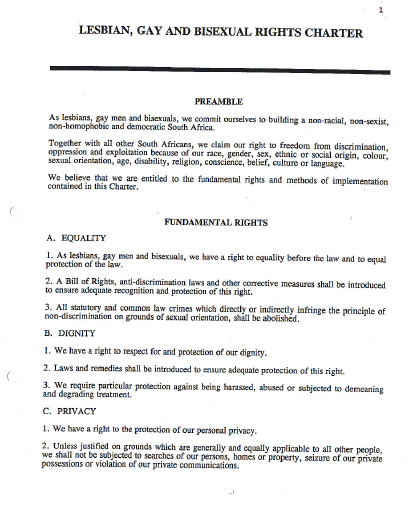

A ‘Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Rights Charter’

In consultation with other lesbian and gay organisations, OLGA compiled the final version of the ‘Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Rights Charter’. It was endorsed at a national conference in Cape Town which had been convened to forge a united campaign for constitutional protection. Shortly thereafter, OLGA dissolved but the struggle for gay and lesbian rights would continue under the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality.

1994

The Mother City Queer Project (MCQP) and

Pride Parade

The MCQP hosted a large and inclusive party in celebration of the constitutional recognition of the right to sexual freedom in the Interim Constitution. Cape Town also hosted a second pride march. But some members of the pride committee argued that queer people were now free and there was no longer a need to publicly protest. Others felt differently. By the late 1990s, the Pride March morphed into the Pride Parade. Routes changed, fees were charged and according to Beverly Ditsie, it then became unrecognisable: “An entirely different, depoliticised, elitist concept born of ignorance and the lack of care for other less privileged members of this so-called community … Gay White South Africa could finally openly celebrate their freedom without being encumbered by the rest of us and our struggles.”

December 1994

Formation of the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality (NCGLE)

Zackie Achmat conceived, launched and led NCGLE for its first five years together with activists like Phumzile Mtetwa. The Coalition united all factions – about 70 lesbian, gay and human rights organisations - in a concerted drive to persuade the Constitutional Assembly to retain ‘sexual orientation’ from the Interim Constitution's equality clause. The Coalition’s work included coordinating members’ actions and ensuring that lobbying efforts reflected the racial and linguistic diversity of gay and lesbian South Africans. NCGLE prepared submissions to the Constitutional Assembly and orchestrated very successful letter-writing, petition, and postcard campaigns to promote “equality for all”.

1994

The Hope & Unity Metropolitan Community Church (HUMCC)

The HUMCC was established in 1994 by Reverend Tsietsi Thandekiso. Its first home was in rented rooms above the Skyline Bar in Hillbrow. For 18 years it served as a spiritual home to those seeking guidance in reconciling their sexual identity with their relationships with God. After Thandekiso’s death in 1997, Reverend Nokuthula Dhladhla and Reverend Paul Mokgethi-Heath took over the leadership of the church. Many GLOW activists were congregants in the HUMCC.

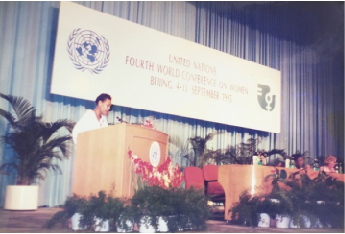

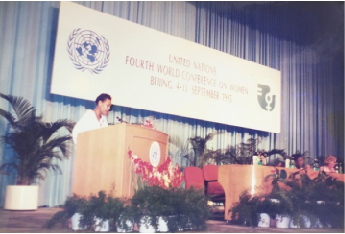

September 1995

The United Nations (UN) Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, China

Male members of GLOW were unsupportive of Beverley Palesa Ditsie when she was invited to represent GLOW at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. They believed that a woman at the forefront of the organisation would take attention away from the more pressing gay issues. But Ditsie attended the conference and the statements that she made there as a gay rights activist were hugely significant. She was the first openly lesbian person to take to the podium and it was the first time that the UN was urged to consider the realities of LGBTQIA+ people in the protection of human rights. She said:

“If [this] conference is to address the concerns of all women, it must similarly recognise that discrimination based on sexual orientation is a violation of basic human rights … Every day, in countries around the world, lesbians suffer violence, harassment and discrimination because of their sexual orientation … Women who love women are fired from their jobs; forced into marriages; beaten and murdered in their homes and on the streets; and have their children taken away by hostile courts. Some commit suicide due to the isolation and stigma that they experience within their families, religious institutions and their broader community.”

Nkateko - a lesbian activist group

In 1995, Bev Ditsie and other prominent members of GLOW left to form Nkateko, the Tsonga word for success. This was partly in response to the invisibility of black lesbian issues, sexism, and the dominance of white men and women in GLOW and partly in response to GLOW’s perceived sexism in relation to the Beijing conference. The primary issues Nkateko addressed were homelessness, ‘coming out’, violence, and homophobia.

February 1995 - 1996

NCGLE’s contributions to the final text of the Constitution

The NCGLE commenced its activities after affiliate organisations elected representatives to an interim executive committee. The coalition’s lobbying process to have the phrase ‘sexual orientation’ included in the equality clause of the final Constitution, brought together a relatively fractured gay and lesbian community. NCGLE’s strategy focused on a narrative of equality and non-discrimination. As Graham Reid explained, “it was important that the coalition wouldn’t speak about gay rights, only about equality.” In the end, virtually all the parties supported its inclusion and the clause was ultimately retained. The single-issue focus of the NCGLE was believed to be the reason for its success.

December 1996

The New Constitution

“It was absolutely exhilarating when Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s first democratically elected president, announced a constitutional order where regardless of colour, gender, religion, political opinion or sexual orientation, the law will provide for the protection of all its citizens. It was the first constitution in the world that mentioned sexual orientation. ”

-Edwin Cameron, gay rights activist and former Justice of the Constitutional Court

The sexual orientation clause in the Bill of Rights reads:

“3. The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.

4. No person may unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds in terms of subsection (3).”

November 1998

Zackie Achmat and the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC)

Ten days after the death of Simon Nkoli from HIV/AIDS on 30 November 1998, LGBTQI rights activist, Zackie Achmat, founded the TAC. The organisation aimed to mobilize people to campaign for access to medicines for people with HIV and AIDS throughout Africa and more generally for the right to health. Achmat declared that he was himself living with HIV and later refused to take antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) that were available to him until all who needed them had access to them.

He held firm in his pledge until August 2003 when, after persuasion from TAC activists, and from former President Mandela personally, he agreed to start treatment. This was shortly before the government announced that it would make antiretrovirals available in the public sector. Achmat and the TAC vigorously and ingeniously confronted President Thabo Mbeki’s HIV/AIDS denialism, showing how many HIV-related deaths could have been prevented by timely implementation of access to anti-HIV drugs. The TAC's campaign culminated in its biggest victory - the Constitutional Court’s decision in July 2002 ordering President Mbeki's government to start making ARVs available.

Constitutional court cases and victories for the LGBTQIA+ community

Despite the prohibition of unfair discrimination based on sexual orientation in the 1996 Constitution, the laws prohibiting consensual sex between two men as well as other discriminatory laws, remained on the statute books. Widespread negative social attitudes to LGBTI people also remained. Lobby groups and gay rights activists were clear that further legal and social changes were necessary if the Constitution was to become meaningful.

Well known gay right activist and lawyer, Edwin Cameron, together with other activists involved in this legal space, helped to devise a litigation strategy for the NCGLE. It was based on a ‘gradualist approach’ with listed goals for the movement. It proposed that litigation should start with the least controversial and most winnable objectives, such as the decriminalization of same-sex sexuality and achieving an equal age of consent. Thereafter, the strategy would focus on specific partnership rights which would eventually result in the recognition of same-sex marriage and adoption.

1999

The first judgment in the Court on LGBTI rights

In the case of the National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality v Minister of Justice and Others, NCGLE and the South African Human Rights Commission challenged the constitutionality of existing laws which criminalized sodomy. The court focused on the equality clause and drew on previous tests for determining unfair discrimination. In its landmark ruling, the court considered the harmful social and psychological impact of the criminalization of sodomy on gay men and found that it fundamentally affected their dignity. The provisions of the Sodomy Act were found to be unfair and declared unconstitutional. This was a great victory for the LGBTQIA+ community and provided a framework for future judgments.

“I was no longer a criminal in terms of the Sexual Offences Act. It gave me hope, because I felt like a citizen of South Africa.”

-Mr Vusi Msiza, LBGTQIA+ Activist

2000

Recognising the rights of lesbian and gay partnerships

In the case, National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and Others v Minister of Home Affairs and Others, the Constitutional Court had to consider whether a provision of the Immigration Act was constitutional. The provision allowed a foreign opposite-sex partner of a South African citizen to live in South Africa but denied the same treatment to a foreign same-sex partner of a South African. The court found that the statute unfairly excluded same-sex couples. It introduced the notion of ‘reading in’ particular words to a statute rather than sending it back to Parliament and ordered that the words “or partner in a permanent same-sex life partnership” be added to the act.

2002

Extending the rights accorded to same-sex life partners

The LBGQTIA+ community steadily continued to make significant gains in the courtroom to expand their freedoms. Once lesbian and gay partnerships had been recognized in the Immigration Act, several other cases followed which accorded rights to same-sex life partnerships. These included pension benefits (Satchwell v. President of the Republic of South Africa, 2002), adoption rights (Du Toit v. Minister of Welfare and Population Development, 2003) and the right of a lesbian couple to artificial insemination (J v. Director General, Department of Home Affairs, 2003). All of these cases focused on the unfair discrimination of particular laws and the infringement of the dignity of the partnership. They resulted in the courts order to read in the words ‘or permanent same-sex life partnership’ so as to extend the rights in question to same-sex couples.

“The applicants constitute a stable, loving and happy family … This failure by the law to recognise the value and worth of the first applicant as a parent to the siblings is demeaning. I accordingly hold that the impugned provisions limit the right of the first applicant to dignity.”

-Acting Justice Thembile Skweyiya, in the Du Toit judgment, 10 September 2002

“The state is required by section 7(2) of the Constitution to “respect, protect, promote and fulfil the rights in the Bill of Rights … The executive and legislature are therefore obliged to deal comprehensively and timeously with existing unfair discrimination against gays and lesbians.”

-Justice Richard Goldstone, in the J and B judgment, 28 March 2003

2006

The Civil Union Act

The victories won in the courts for same sex couples were very significant but were still considered to be piecemeal changes to the legislation. The time had come for a more comprehensive challenge to regularize relationships between gay and lesbian partners. The institution of marriage – with its symbolic and practical implications - now came under the spotlight in the case of Minister of Home Affairs v. Fourie, Marié Fourie and Cecelia Bonthuys.

Fourie and Bonthuys, who had been living together in an exclusive relationship since 1994, claimed that they had been unfairly discriminated against because they were not allowed to get married under the Marriage Act 25 of 1961. In an important landmark judgment, the Constitutional Court found that the Marriage Act was unconstitutional and violated section 9 of the Constitution – the Right to Equality. Instead of simply ‘reading new words’ into the Marriage Act, the Court gave Parliament one year to pass new legislation. The Civil Union Act 17 came into force in 2006, making South Africa the first country in Africa, and the fifth in the world, to legalise same-sex marriages.

“We just want that little white piece of paper.”

-Marie Fourie, Applicant to the Constitutional Court, 2005

“The exclusion of same-sex couples from this institution ‘represents a harsh if oblique statement by the law that same-sex couples are outsiders, and that their need for affirmation and protection of their intimate relations as human beings is somehow less than that of heterosexual couples.”

-Justice Albie Sachs, in the Fourie judgment, 2006

“The court in this case recognized that the matter touched strong public and private sensibilities and that the legislature is better-suited to finding the best way to include protections for same-sex couples. Moreover, the court indicated that lasting legislative action will be more likely to concretize the search for equality by lesbian and gay people.”

-David Bilchitz, lawyer and gay rights activist

2019

Caster Semenya banned from competing

Caster Semenya is a highly accomplished South African athlete who won gold at the 2016 Olympic games and who has broken multiple records. Since the start of her athletic career, she has been subjected to unrelenting questioning over her gender and whether she has an unfair biological advantage in women’s competitive athletics. In 2019, the International Association of Athletic Federations ruled that women such as Semenya cannot compete in athletic events unless they take medication to lower their testosterone levels. Caster continues to challenge this decision and plans to continue to fight for her ability to race.

“I am Mokgadi Caster Semenya. I am a woman and I am fast.”

-Caster Semenya

“Semenya, who is South African, identifies as a woman and has never publicly discussed her medical history. But ever since she arrived on the global scene a decade ago, she’s been subject to constant scrutiny, as the media, the public, and her fellow athletes speculated about her anatomy, misgendered her, and argued that she shouldn’t be allowed to race against other women. Her career is a reminder that when people challenge perceived ideas about masculinity and femininity, their bodies can become fodder for public discussion — often against their will.”

-Anna North, Vox, 3 May 2019

Today's Issues

“The Constitution is beautiful on paper but in reality, it is not"

After the signing of the Constitution, LGBTQIA+ people were encouraged to lead their lives more openly. Increasing numbers of people came out and became more visible. But there was at the same time an increase in discrimination, stigmatisation, marginalisation, violence, sexual assault and even murder. Beverley Palesa Ditsie, member of Nkateko, commented: “Even after the new Constitution was adopted in 1996 which ensured our rights, the violence and intimidation continued unabated, especially for those of us in the townships, rural areas, in homophobic homes and communities. We marched to continue to reclaim our dignity and our rightful space in society.” There are still several active and visible LGBTQIA+ organisations campaigning to address the issue of hate crimes and violence.

2000s

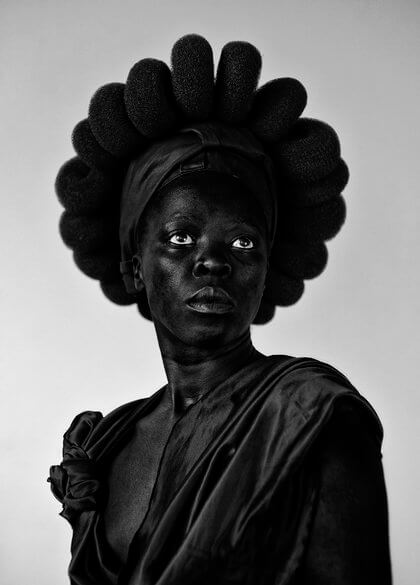

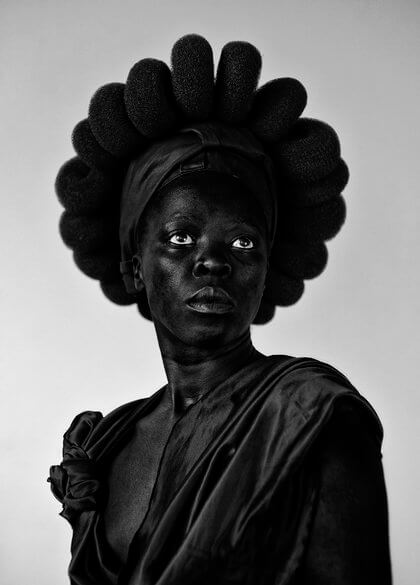

Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi, a South African artist and activist working in photography, video, and installation, was born in Durban in 1972 at the height of apartheid. In the early 2000s, Muholi began to raise awareness of the hate crimes and violence that was all too prevalent in the South African LGBTQI+ community. She did this by taking portraits that showed that individuals in the black queer community are beautiful and courageous and have the same lives, loves and aspirations as anyone else. Her work has been praised around the world for promoting mutual understanding and respect. Muholi herself most often describes her photography as ‘healing’. Her ongoing series of performative self-portraits use symbolic poses and props to address issues of race and representation as a queer woman.

2000s

Expansion of the gender lexicon

Since the drafting of the Constitution in 1996, there has been a dramatic expansion of the gender lexicon and the recognition of different sexual identities. The abbreviation used today to represent these identities is LGBTQIA+. The 'Q' is for ‘queer’, a catchall term often used to refer to all of those who are part of the LBGTQIA+ community. The ‘I’ and ‘A’ represent those who identify as intersexual and asexual respectively. The ‘+’ sign denotes the possibility of further identities.

Bilchitz, D (2015) “Constitutional change and participation of LGBTI groups: A case study of South Africa”, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

Brown, T (2014) “South Africa’s gay revolution: the development of gay and lesbian rights in South Africa’s constitution and the lingering societal stigma towards the country’s homosexuals”, Elon Law Review

Christiansen, E (2000) Ending the Apartheid of the Closet: Sexual Orientation in the South African Constitutional Process, N.Y.U.J. of Int’l Law & Politics

Cock, J (2002) “Engendering gay and lesbian rights: the equality clause in the South African constitution”, Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 35 – 45, Elsevier Science Ltd

Ditsie, B (2019) “Love letter to my queer family”, Mail and Guardian https://mg.co.za/article/2019-10-24-00-love-letter-to-my-queer-family/

Smith, A (2005) “Where Was I in the Eighties?”, Sex and Politics in South Africa, edited by Neville Hoad, Karen Martin, and Graeme Reid, Cape Town: Double Storey Books

de Ru, H (2013) “A historical perspective on the recognition of same-sex unions in South Africa”, Fundamina, vol.19

Jackson, J (2019) “Roots of Revolution: The African National Congress and Gay Liberation in South Africa”, University of Florida Levin College of Law

Gevisser, M and Cameron, E eds (1995) Defiant Desire, Taylor Francis

Tatchell, P “South Africa: How the ANC was won for LGBT rights”

Tobia, J (2014) “Out of the Laager, Into the Streets: The Origins, Rise, and Fall of Gay Reform Organizing in Apartheid South Africa”, Honors in Program II: Human Rights Activism and Leadership, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina

https://www.mambaonline.com/2019/04/29/a-timeline-of-lgbtq-equality-in-south-africa/

https://www.petertatchellfoundation.org/south-africa-how-the-anc-was-won-for-lgbt-rights/

https://issafrica.org/amp/iss-today/classifying-corrective-rape-as-a-hate-crime-in-south-africa